Premium Only Content

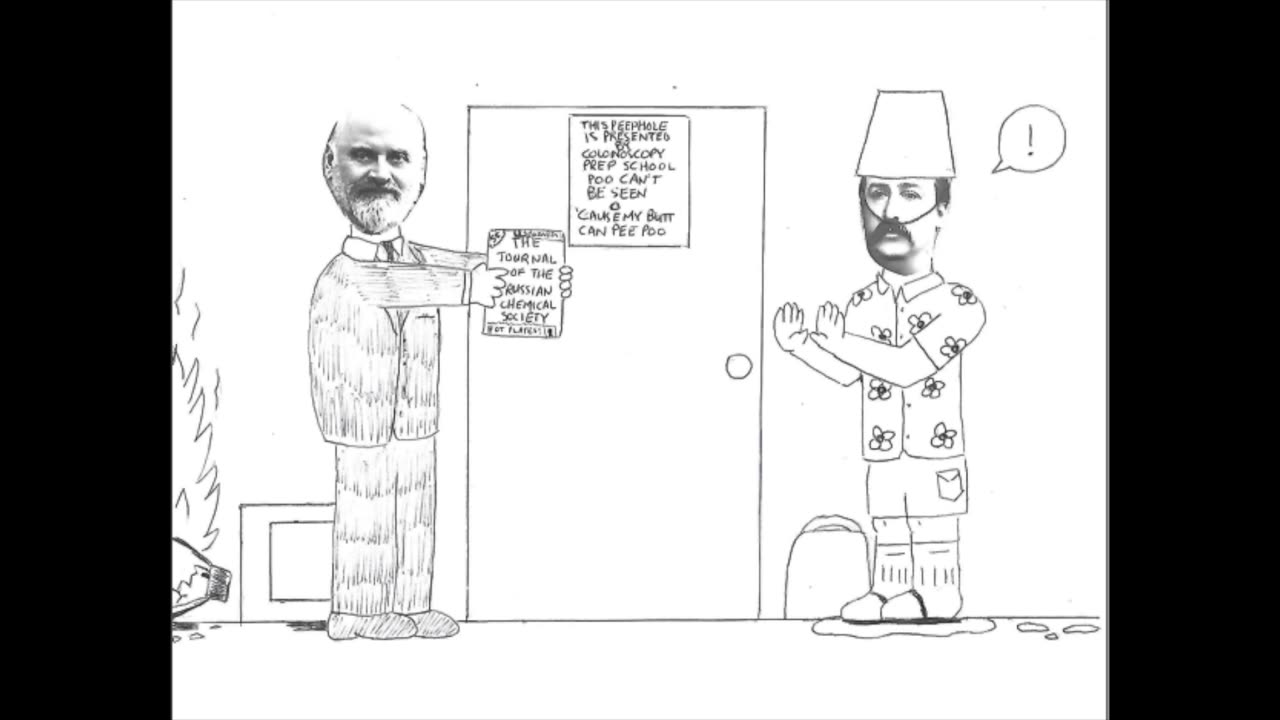

Love Me Two-Timer

This sketch was inspired by an incident a member of our troupe experienced a few years ago. He started taking piano lessons early in 2018 from a teacher who was an organist at a local church. In mid-2018, this troupe member learned that his brother had in his possession a violin from their late father, a music professor. This troupe member thought it would be fun to restore the violin, find a teacher, and learn to play it. In 2019, this troupe member showed up for his piano lesson at his teacher’s house. He tried to take a piano book out of his book bag but inadvertently took out one of his violin books instead. The piano teacher (a female) saw the violin book and looked at the troupe member almost as if he was her husband and she had just seen incriminating lipstick on his collar. So this troupe member wrote this sketch featuring Alexander Borodin (1833-1887), who excelled at chemistry and composing. And let’s face it folks, Borodin was, broadly speaking, just like our aforementioned violin/piano student, a two-timer.

The “two-timer” reference in this sketch really reaches beyond the romantic aspect of the word. While many people may consider Borodin a very intelligent individual because he was good at two completely different fields, CoBaD doesn’t really share that opinion. Thanks to painful experience, CoBaD firmly subscribes to the “Jack of all trades, master of none” idiom. While Borodin was indeed good at chemistry and composing, CoBaD often wonders how much better a chemist he could have been had he solely focused on chemistry, or how much better a composer he could have been had he focused solely on music. To a smaller extent, having spoken to the aforementioned violin teacher referred to in the opening paragraph, switching back and forth between orchestras (specifically operas) and chamber music, as Mily Balakirev (1837-1910) did in this sketch, presents its own set of unique challenges as well.

Caption: “Dammit, you imbeciles, it’s St. Petersburg, Russia, not St. Petersburg, Florida! Didn’t you learn anything from the R-K sketch?!” – For more on the background behind the background, see the “No, But If You Hum A Few Bars I’ll Name It” sketch.

Caption: “Don’t make me Lambert your ass like I did to Camera One!” - For more on the “decorated” history of Lambert (specifically his decoration of rolled up scripts, music scores and coffee tables), see the “Daydream Bleacher,” “I Tried Improvisation, Then I Was Perturbed,” “Booth Estranges Diction” and the “No, But If You Hum A Few Bars I’ll Name It” sketches. For more on poor Mr. Camera 1, see the “Daydream Bleacher” and “Booth Estranges Diction” sketches.

Mily: “Now if you need to take a quick poopy break, I’ve arranged with Hobson’s Choice Horse Rental Agency down the street to use his stalls. Now Hobbie’s a bit mean and an aggressive sort, but otherwise he’s simply darling!” – For more on the Hobson’s Choice Horse Rental Agency, see the “Earp Family Reunion” sketch.

Mily: “You call that an opera? A five scene comedy? What a farce! It’s so inadequate!” – Mily here is referring to “Bogatyri (The Heroic Warriors)” (1878), an opera-farce in five scenes. Only one quarter of the music was originally composed by Borodin. The rest was based on music by Rossini, Meyerbeer, Offenbach, Serov and Verdi.

Mily: “You can’t even last longer than one act with without calling for relief! “ - Borodin started work on “The Tsar’s Bride” (1867), but it never got past musical sketches. Those sketches are now lost. Incidentally, this line is almost verbatim what Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) once said about Borodin, whom he claimed "has talent, even a strong one, but it has perished through neglect ... and his technique is so weak that he cannot write a single line [of music] without outside help."

Borodin started “Prince Igor” in 1869. It too remained unfinished at the time of his death in 1887. It was completed by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov and Alexander Glazunov.

“Mlada” (1872) was a collaborate opera-ballet conceived by Stepan Gedeonov. The music was a collaborative effort between Borodin, César Cui, Modest Mussorgsky and Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov (more on those last three composers later). Borodin wrote Act 4. The project was never completed. This “Mlada” should not be confused with Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov’s opera-ballet of the same name, which premiered in 1890.

Mily: “Now Verdi, he’s different! He can give me more! He can go longer! Grander! Multiple premieres!” - Several of Giuseppe Verdi’s operas in fact had multiple premieres:

1. Jerusalem (1847, a revision and translation of I Lombardi alla prima crociata (1843),

2. Giovanna de Guzman (1855, a revision and translation of Les vêpres siciliennes, 1855),

3. Le trouvère (1856, a revision and translation of Il trovatore, 1853),

4. Aroldo (1857, a revision of Stiffelio, 1850)

5. Macbeth (1847, 1865)

6. Don Carlo (1867a, 1867b, 1872, 1884, 1886)

7. La forza del destino (1862, 1869)

8. Simon Boccanegra (1857, 1881)

Verdi: “Mily, don’t hang around with this here loser! Just say the word and we’ll travel! We’ll go to Milan and see Egypt! We’ll go to Naples and see Spain and France!” – Verdi opera “Aida” is based in Egypt. “Milan” here is referring to La Scala Opera House in Milan, Italy. While technically the opera premiered in Cairo, Egypt in 1871, Verdi considered the official premiere to be in La Scala on 8 February 1872.

Verdi’s “Don Carlo” is based in France and Spain. Rewritten multiple times, it had five “premieres” (see above), the third one taking place in Naples in late 1872.

Verdi: “And are you going to leave me for a man who plays with animal piss!?” - Borodin’s last publication discussed a method for the identification of urea in animal urine.

Alexander (to Verdi): ”Kismet my ass, Verdi!!” - Much of the music in the musical “Kismet” was based on works by Alexander Borodin. Borodin was in fact given a posthumous Tony Award in 1954.

Mily: “Here we are! ‘How to Play Redundant Piobaireachds on the Violin like Lindsey Stirling’!” – For more on redundant piobaireachds, see the “Crunluath a Mock” sketch.

Mily: “Darn it!!! I do so hate barre class! Damn that Tchaikovsky! He never should have invented ballet!” – In the 1860s, Mily Balakirev led a group of Russian composers known as “The Five”: Balakirev, Alexander Borodin, César Cui, Modest Mussorgsky, and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. Note the conspicuous absence of Tchaikovsky from this group. This is mainly because “The Five” and Tchaikovsky had a difference of opinion on the direction of Russian classical music. “The Five” wanted to produce a specifically Russian kind of music. While Tchaikovsky wasn’t opposed to writing music that was distinctly Russian (e.g., some of his works, such as his “1812 Overture,” borrow Russian folk songs), Tchaikovsky for the most part wanted to write compositions that would follow European styles and techniques, thereby crossing national barriers. In addition, none of “The Five” was academically trained in composition. Balakirev, the overbearing, often dictatorial leader of “The Five,” in fact considered academics a threat to musical imagination. Balakirev repeatedly attacked the Saint Petersburg Conservatory, its founder, Anton Rubinstein, and one of its most famous graduates, Tchaikovsky, both orally and in print. Balakirev and Tchaikovsky would later become friends, but not intimately so, as their philosophies were still (and would remain) worlds apart.

References:

IMSLP. List of works by Aleksandr Borodin. https://imslp.org/wiki/List_of_works_by_Aleksandr_Borodin

Wikipedia. Aida. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aida

Wikipedia. Alexander Borodin. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexander_Borodin

Wikipedia. List of compositions by Giuseppe Verdi. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_compositions_by_Giuseppe_Verdi

Wikipedia. Mily Balakirev. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mily_Balakirev

Wikipedia. Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and The Five. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pyotr_Ilyich_Tchaikovsky_and_The_Five

-

LIVE

LIVE

Nerdrotic

3 hours ago $1.66 earnedGobekli Tepe Coverup, Pyramid Structures w/ Jimmy Corsetti & Wandering Wolf | Forbidden Frontier 096

1,268 watching -

LIVE

LIVE

SpartakusLIVE

1 hour ago#1 Action HERO ends your weekend in a FIERY BLAZE of non-stop GLORY

484 watching -

54:47

54:47

Sarah Westall

3 hours agoTranshumanism vs Natural Human Zones, AI consciousness and the Hive Mind Future w/ Joe Allen

6.98K4 -

LIVE

LIVE

The Sufari Hub

1 hour ago🔴ELDEN RING MODDED - ROAD TO #1 GAMER ON RUMBLE - #RumbleGaming

37 watching -

![[LIVE] The Sunday Surprise! | Counter Strike w/ Omega (Meisters Madness)](https://1a-1791.com/video/fww1/70/s8/1/U/P/W/x/UPWxy.0kob-small-LIVE-The-Sunday-Surprise-A-.jpg) LIVE

LIVE

Joke65

1 hour ago[LIVE] The Sunday Surprise! | Counter Strike w/ Omega (Meisters Madness)

16 watching -

LIVE

LIVE

MaverickLIVE

1 hour agoFirst Rumble Stream!

72 watching -

LIVE

LIVE

xTimsanityx

5 hours ago🟢LIVE: COACH ALWAYS TOLD ME, "SHOOTERS SHOOT" | GOONING ON E-DISTRICT

46 watching -

32:19

32:19

SB Mowing

2 days agoThis yard was putting KIDS IN DANGER - Now they can SAFELY play outside again

7.91K16 -

LIVE

LIVE

Lofi Girl

2 years agolofi hip hop radio 📚 - beats to relax/study to

735 watching -

47:41

47:41

Tactical Advisor

4 hours agoMake Your AR15 into a Bullpup/New Thermals | Vault Room Live Stream 018

28.1K11