Premium Only Content

The Stanford Trial Experiment

The Stanford Trial Experiment is a fictional follow up study to Dr. Philip Zimbardo’s famous Stanford Prison Experiment. Scheduled to run for two weeks in the summer of 1971, the Stanford Prison Experiment was called off after only six days when it became quite clear that all those who were involved in the study became so immersed in their roles (the college students who played the prison guards, the prisoners, and even Dr. Zimbardo himself as the prison superintendent) that they soon forgot that it was in fact a simulation. While it is easy to explain the prisoners’ descent into violence (they were physically immersed in the environment at all times: they were “arrested” at their homes, they were booked, they slept in cells, they wore numbers, they were called out by numbers, etc.), the guards were probably more fascinating: the guards worked in eight hour shifts and got to leave the “prison,” go home and go about their normal lives (we assume that they were not allowed to talk about the experiment). When they reintegrated themselves into the prison environment, their reintegration was very quick after only five days. So while the key question in the Stanford Prison Experiment (according to prisonexp.org) was “What happens when you put good people in an evil place?” the key question in the Stanford Trial Experiment was “What happens when you put sensible people in a very silly place?”

The Human Exploitation Review League (HERL) is an obvious spoof of an ethics review board. In the history of psychology there have been several experiments (e.g., Watson’s “Little Albert” experiment, Milgram’s “Obedience to Authority” experiment, Zimbardo’s “Stanford Prison Experiment”) which, through the lens of hindsight, are perceived as being controversial and unethical. So HERL attempts to put a stop to this runaway rash of “unethical” behavior in experiments. In reality, the board grossly overcompensates and becomes a vast, slow to respond, foot-dragging, bribe taking bureaucracy which bogs down its experimenters with endless rules, regulations, consent forms and nondisclosure agreements, essentially making experimenters have to conduct dozens of experiments costing millions of dollars in order to get results that would only gather a fraction of the data that an “unethical” experiment would collect. So in a sense the title of the League is quite accurate: human exploitation is their forte - they exploit (human) experimenters. Truth be told, ethics boards don’t really exploit experimenters like this. A member of our troupe worked with review boards, and they were very nice and helpful.

The key takeaway from all this is: Would we have learned as much about human behavior if Dr. Zimbardo’s Prison Experiment (or Milgram’s or Watson’s experiments for that matter) had been held to today’s ethics standards? Probably not, which brings up another point. A puzzling aspect to the aforementioned studies is that they are still prominently featured in psychology textbooks. Is it for the shock and entertainment value (see the “The New York Times’ Effect on Man” skit for a further discussion on this)? It seems that textbooks authors, in keeping these studies in their textbooks, are suggesting that it is okay to use the information gathered in these studies to illustrate a point even though the studies may have been unethical. It seems like textbooks should set an example that it is not okay to use data from experiments that were conducted unethically.

416 was the actual number of a prisoner in the Stanford Prison Experiment who on day five went on a hunger strike. In the 1959 movie “Ben Hur,” “41” was the name given to Ben Hur when he was a slave on the galley ship.

When the defense attorney says in his objection, “Personal conscience has nothing to do with my client’s condition,” technically that statement is true, at least from a methodological perspective. For the prisoner condition in the Stanford Prison Experiment, Zimbardo was looking at how prisoners would respond when their freedoms and identities were suddenly stripped away. For the prison guard condition, Dr. Zimbardo was looking at personal conscience.

The title of the ethics board, Human Exploitation Review League (HERL), is a play on the term Human Integration Readiness Level (HIRL). A member of our troupe is a Human Factors engineer. HIRL is a Human Factors term which basically measures on a scale from 1 to 9 how effectively and safely the human operator or maintainer can use a fielded technology. Yet the aforementioned Human Factors engineer couldn’t take this term seriously because every time he would look at the acronym, he would giggle and jokingly cry out “I think I’m gonna HIRL!” The engineers probably heard him because the generally accepted acronym nowadays is Human Readiness Level (HRL).

The paragraph Dr. Vomit cites at the end of the skit (Part II, subpart A, section 49, paragraph (a)) is the Code of Federal Regulations Title 14 paragraph as it pertains to student pilots who wish to retest after a failed check ride. I guess one could say that a sequel is kind of a retest.

To find out more about the Stanford Prison Experiment, CoBaD recommends visiting www.prisonexp.org

-

LIVE

LIVE

SportsPicks

2 hours agoCrick's Corner: Episode 72

72 watching -

30:39

30:39

ROSE UNPLUGGED

1 hour agoMore of Less: Purpose, Discipline & the Minimalist Mindset

10 -

1:02:18

1:02:18

Timcast

3 hours agoDemocrat States Ignore English Language Mandate For Truckers, DoT Vows Crackdown Amid Trucker Mayhem

136K40 -

1:57:04

1:57:04

Steven Crowder

6 hours agoAdios & Ni Hao: Trump Sends Abrego Garcia to Africa But Welcomes 600K Chinese to America

292K261 -

LIVE

LIVE

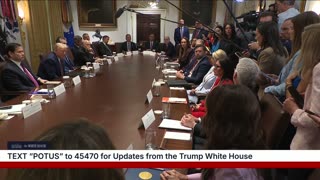

The White House

5 hours agoPresident Trump Participates in a Cabinet Meeting, Aug. 26, 2025

2,378 watching -

1:18:51

1:18:51

Rebel News

2 hours agoCarney's flawed LNG deal, Libs keep mass immigration, Poilievre's plan to fix it | Rebel Roundup

16.6K8 -

27:39

27:39

Crypto.com

5 hours ago2025 Live AMA with Kris Marszalek, Co-Founder & CEO of Crypto.com

68.1K4 -

56:18

56:18

TheAlecLaceShow

3 hours agoMAGA Pushback Against Flag Burning EO & 600K Chinese Students | Cashless Bail | The Alec Lace Show

15.2K -

1:09:18

1:09:18

SGT Report

17 hours agoBIOHACKING 101: MAKING BIG PHARMA IRRELEVANT -- Dr. Diane Kazer

34.4K20 -

4:58:31

4:58:31

JuicyJohns

7 hours ago $1.81 earned🟢#1 REBIRTH PLAYER 10.2+ KD🟢

51.9K