Premium Only Content

How a Female Sniper Used a “Suicidal” Tactic to Kill 309 Germans in 11 Months

V.O:

At 5:47 a.m. on August 8th, 1941, twenty-four-year-old Ludmila Pavlichenko crouched behind a pile of rubble in Belaya Tserkov, Ukraine, watching a German sniper take aim at a Soviet soldier just forty meters to her left. She had been in the Red Army for four months, had zero confirmed kills, and didn’t yet know she would eventually rack up three hundred and nine. The Wehrmacht had sent three full divisions toward Odessa, one hundred fifty thousand soldiers advancing while the Soviets were outnumbered three to one. Ludmila had volunteered for sniper duty in a unit losing people faster than they could train replacements. She had been awake for almost a full day—no sleep, no food, just her Mosin–Nagant rifle, forty rounds of ammunition, and a rage born from loss. Eleven days earlier, her university in Kyiv had been bombed. Seventy-three students killed. Her professor, Dr. Vulov, crushed under rubble. Her best friend Natasha burned alive inside the library. Ludmila enlisted the next morning. The recruiting officer tried to send her to a medical unit. Women, he said, belonged with bandages, not rifles. She told him she’d been shooting since she was fourteen, top scores in youth competitions. He laughed until she put five rounds through the center of a fence post at one hundred meters. He stopped laughing and assigned her to the 25th Rifle Division as a sniper. Four months later, she was lying in ruins, watching Germans kill her comrades while she hadn’t taken a single shot. The German sniper was two hundred eighty meters away, tucked behind a shattered farmhouse wall. Through a thin crack, she could see the edge of his helmet as he tracked his target—Sergeant Dmitri Kravchenko, a thirty-two-year-old father of two who had shared his bread with her after she’d gone eighteen hours without food. He didn’t know death was seconds away. Ludmila lifted her rifle. Her hands were steady. Her breath slowed. Her instructor’s voice echoed in her mind: don’t think about killing, think about solving a problem—distance, wind, timing. Math, not murder. Two hundred eighty meters. Light crosswind. Target still. She adjusted, settled the sights on that thin crack in the wall, and touched the trigger. This was the moment that would decide whether she was a real soldier or a student pretending to be one. She squeezed. The rifle kicked hard. The crack of the shot rolled through the battlefield. Through the scope, she saw the German’s helmet snap back and vanish. Kravchenko froze, confused, unaware he’d just survived. Ludmila chambered another round and scanned for movement. Nothing. Silence. Her first kill. She felt no guilt, no pride, just one instinctive thought: where’s the next one? That was August 8th, 1941. By May of the next year, that same young woman would have three hundred nine confirmed kills, including thirty-six enemy snipers, becoming the deadliest female sniper in history. And she would survive by doing something the Soviet manual strictly forbade—she used herself as bait. The first sniper Ludmila ever lost was

-

LIVE

LIVE

The Rabble Wrangler

14 hours agoNew Eastwood Map | The Best in the West Dominates the Battlefield

46 watching -

1:10:42

1:10:42

vivafrei

3 hours agoThomas Crooks Exposé is a BOMBSHELL! Epstein Drama Continues! Alexis Wilkins Streisand Effect & More

113K60 -

1:41:04

1:41:04

The Quartering

4 hours agoEpstein Files Takes Its First Scalp, MTG Unleashes, Kash Patel Blasted, Internet Outage & More

117K85 -

24:53

24:53

Jasmin Laine

2 hours ago“NO ONE BELIEVES YOU”—Carney Gets HUMILIATED in BRUTAL Showdown

4.36K10 -

LIVE

LIVE

LFA TV

20 hours agoLIVE & BREAKING NEWS! | TUESDAY 11/18/25

1,281 watching -

LIVE

LIVE

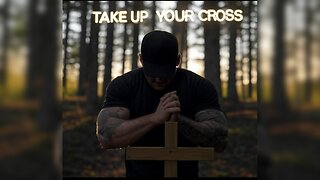

freecastle

7 hours agoTAKE UP YOUR CROSS- The fear of the LORD begins knowledge; Fools despise WISDOM and INSTRUCTION.

140 watching -

5:16

5:16

Buddy Brown

4 hours ago $2.07 earnedWatch INSANE Video of Woman Denied a TINY HOME on 37 Acres! | Buddy Brown

16.1K6 -

59:19

59:19

Professor Nez

4 hours ago🔥 Trump TORCHES ABC Reporter for Disrespecting Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman! (WOW!)

30.2K23 -

7:51

7:51

Dr. Nick Zyrowski

8 hours agoHow To Starve Fat Cells - Not Yourself!

29.1K4 -

1:59:49

1:59:49

The HotSeat With Todd Spears

2 hours agoEP 211: Less Religion, More JESUS!

12.8K20