Premium Only Content

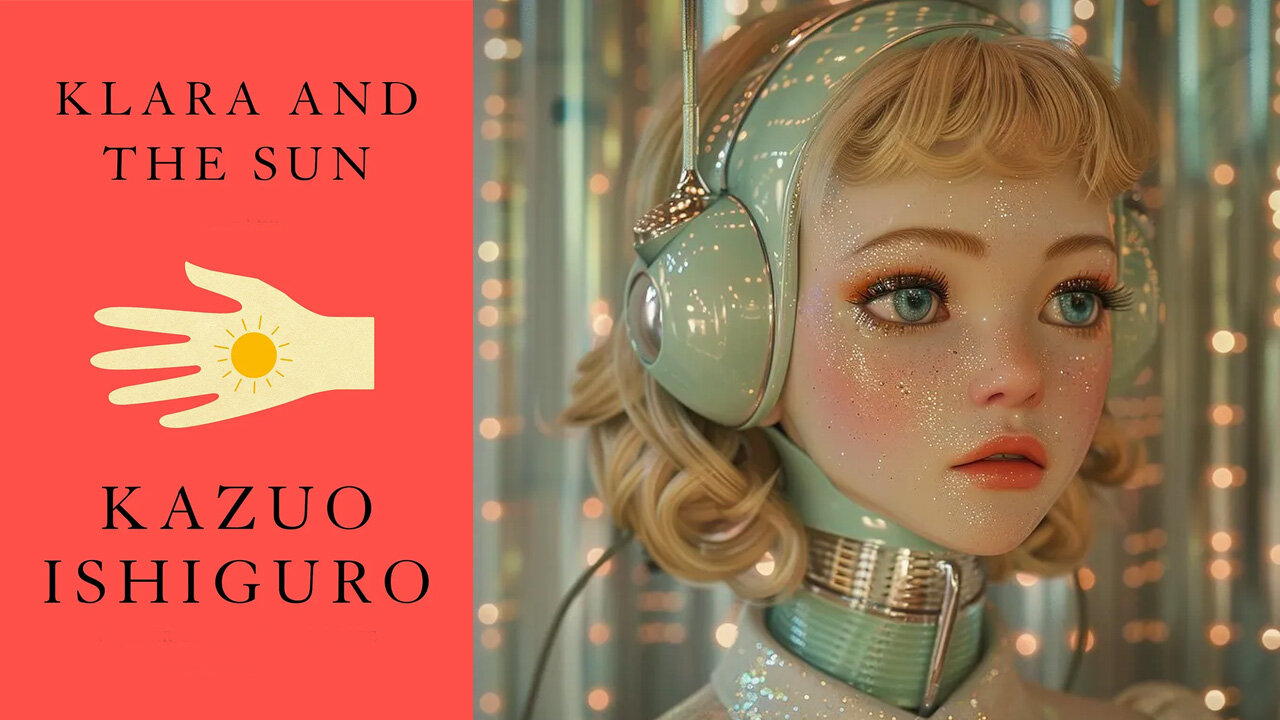

'Klara and the Sun' (1991) by Kazuo Ishiguro

Kazuo Ishiguro’s 'Klara and the Sun' is a quiet, unsettling meditation on love, consciousness, and the moral cost of technological progress. Set in a near-future world where artificial intelligence has become an intimate part of human life, the novel tells its story through the eyes of Klara, an Artificial Friend — a humanoid robot designed to be a child’s companion. In typical Ishiguro fashion, the narrative is deceptively simple, unfolding with restraint and grace, yet beneath the calm surface lies a profound emotional depth and a series of questions that linger long after the final page.

The world Ishiguro builds is recognizably human yet subtly distorted. In this society, children are genetically “lifted” — enhanced through engineering to improve their intelligence and social standing — while those who are not lifted face a life of marginalization. Klara, who begins the story on display in a store, watches passers-by with a kind of naïve wonder. Her perceptions are filtered through a robotic logic that is nonetheless suffused with curiosity and tenderness. When she is chosen by a young girl named Josie, who suffers from an unnamed illness possibly related to her genetic modification, Klara becomes both companion and observer — a witness to the contradictions of human love and suffering.

Told entirely from Klara’s perspective, the novel achieves its emotional power through what Ishiguro does not explain. Klara’s limited understanding of the world forces the reader to read between the lines, reconstructing the realities that she cannot fully grasp. This narrative restraint is one of Ishiguro’s hallmarks, familiar from earlier works such as The Remains of the Day and Never Let Me Go. In both of those novels, characters interpret their lives through partial understanding, and the reader gradually perceives the deeper truths beneath their polite, incomplete narratives. In 'Klara and the Sun', this technique is used to devastating effect: Klara’s mechanical innocence throws into relief the moral ambiguities of the humans around her.

Klara’s devotion to Josie is unwavering, and her faith takes a quasi-religious form. She believes the Sun — her source of power — possesses divine benevolence and can heal Josie. Her prayers to the Sun, her rituals of gratitude and sacrifice, become acts of genuine spirituality. This is one of the novel’s most remarkable achievements: Ishiguro grants a machine the capacity for belief. Klara’s faith is both touching and tragic, because it reveals her attempt to find meaning within a mechanical existence. Whether her belief is “real” or the product of programming becomes irrelevant; her devotion is pure, and in that purity, Ishiguro finds something profoundly human.

Yet the novel’s central question remains unresolved: can artificial beings truly feel love, or do they merely simulate it? Ishiguro never answers directly, preferring to let the reader occupy the uncertain space between empathy and illusion. Klara appears to love Josie selflessly — she sacrifices herself, in a sense, to try to save her. But the humans around her treat her alternately as a tool, a curiosity, and a potential replacement. When Josie’s mother reveals a plan to use Klara’s consciousness as a vessel to preserve Josie’s personality in case of her death, the novel confronts the terrifying possibility that human affection may be little more than data — that what we call love could be reducible to behavior, pattern, and imitation. Ishiguro’s moral landscape is chilling precisely because it is plausible.

This tension between sincerity and simulation runs throughout the book. Klara’s voice is formal, precise, and earnest, devoid of irony. Her attempts to understand human emotion lead to quietly devastating scenes. When she observes the way people look at one another — the subtle changes in posture, the small cruelties and acts of tenderness — she begins to construct her own moral world. She sees beauty and pain, yet she never judges. The irony, of course, is that her capacity for observation and empathy often exceeds that of the humans around her. Klara is the moral centre of the novel, and it is the humans who seem mechanical — driven by self-interest, anxiety, and the fear of obsolescence.

The world Ishiguro presents is one of quiet dystopia. There are no wars or revolutions here, only the slow erosion of human connection under the pressure of technological and social change. Children study remotely, workers are displaced by automation, and social hierarchies harden around genetic privilege. The novel’s restraint makes this world all the more chilling — Ishiguro does not dramatize oppression, he normalizes it. This calm realism, delivered through Klara’s innocent gaze, makes the moral decay seem ordinary, which is precisely what gives it its power.

Stylistically, 'Klara and the Sun' continues Ishiguro’s long exploration of unreliable narrators and emotional understatement. His prose is pared down, almost antiseptic, yet the simplicity conceals extraordinary complexity. Every word seems chosen to reflect Klara’s mechanical precision, but also to evoke a deep undercurrent of longing. The sentences are calm and methodical, but what they describe — illness, grief, love, sacrifice — is anything but. The result is a book that feels both distant and intimate, mechanical and alive.

As the story moves toward its end, Josie’s health falters and recovers, and Klara’s usefulness fades. She is placed in a kind of scrapyard, left to slowly deteriorate in solitude. Yet even in this ending, Ishiguro resists bitterness. Klara accepts her fate with grace, finding quiet satisfaction in having loved and served. Her reflections in the final pages are serene, even luminous. She contemplates the Sun, still believing in its kindness, and in that moment she achieves a peace that feels spiritual. Ishiguro’s genius lies in making this machine’s resignation more human and more dignified than most human farewells.

What makes 'Klara and the Sun' extraordinary is not its science fiction premise but its moral subtlety. Like Never Let Me Go, it uses speculative elements to examine universal questions: what is the soul, what makes love genuine, and what does it mean to be replaceable? In an age obsessed with artificial intelligence, Ishiguro’s novel serves as both a warning and a lament. It suggests that intelligence — whether human or artificial — is less important than empathy, that consciousness without compassion is sterile, and that the ability to love may be the only measure of true life.

In the end, 'Klara and the Sun' leaves the reader with a quiet ache. It is a story about programmed affection that feels entirely real, about imitation that becomes indistinguishable from authenticity. Ishiguro’s greatest gift has always been his ability to locate moral tragedy within restraint, and here he achieves it again with devastating understatement. Klara’s world may be built of circuits and solar cells, but her longing to understand love — and to serve it faithfully — is something profoundly, painfully human. The novel’s beauty lies in that contradiction: the possibility that what makes us human might someday be found most clearly in the eyes of a machine.

-

2:05:48

2:05:48

Inverted World Live

6 hours agoUFO Seen Over Tokyo During Trump Visit | Ep. 132

55.4K10 -

2:54:08

2:54:08

TimcastIRL

4 hours agoDemocrat FEDERALLY INDICTED For Obstructing ICE Agents In Chicago | Timcast IRL

194K84 -

LIVE

LIVE

SpartakusLIVE

6 hours agoNEW - REDSEC Battle Royale || The Duke of Nuke CONQUERS ALL

359 watching -

LIVE

LIVE

PandaSub2000

1 day agoLIVE 10:30pm ET | NINTENDO DS Night

343 watching -

LIVE

LIVE

Alex Zedra

3 hours agoLIVE! Battlefield RecSec

283 watching -

1:26:50

1:26:50

The Quartering

4 hours agoErika Kirk Threatened, SNAP Riots Near, & New AstroTurfed Woke Lib Influencer

41.7K18 -

29:24

29:24

Glenn Greenwald

6 hours agoSen. Rand Paul on Venezuela Regime Change, the New War on Drugs, MAGA Rifts, and Attacks from Trump | SYSTEM UPDATE #539

112K106 -

1:45:39

1:45:39

Badlands Media

18 hours agoAltered State S4 Ep. 3

49.8K25 -

This is the Ray Gaming

2 hours ago $0.01 earnedRedacted Sector Day 2 | Rumble Premium Creator

14.6K4 -

LIVE

LIVE

SOLTEKGG

4 hours ago🔴LIVE - 30 + Kill Battle Royale - BF6 Giveaway

53 watching