Premium Only Content

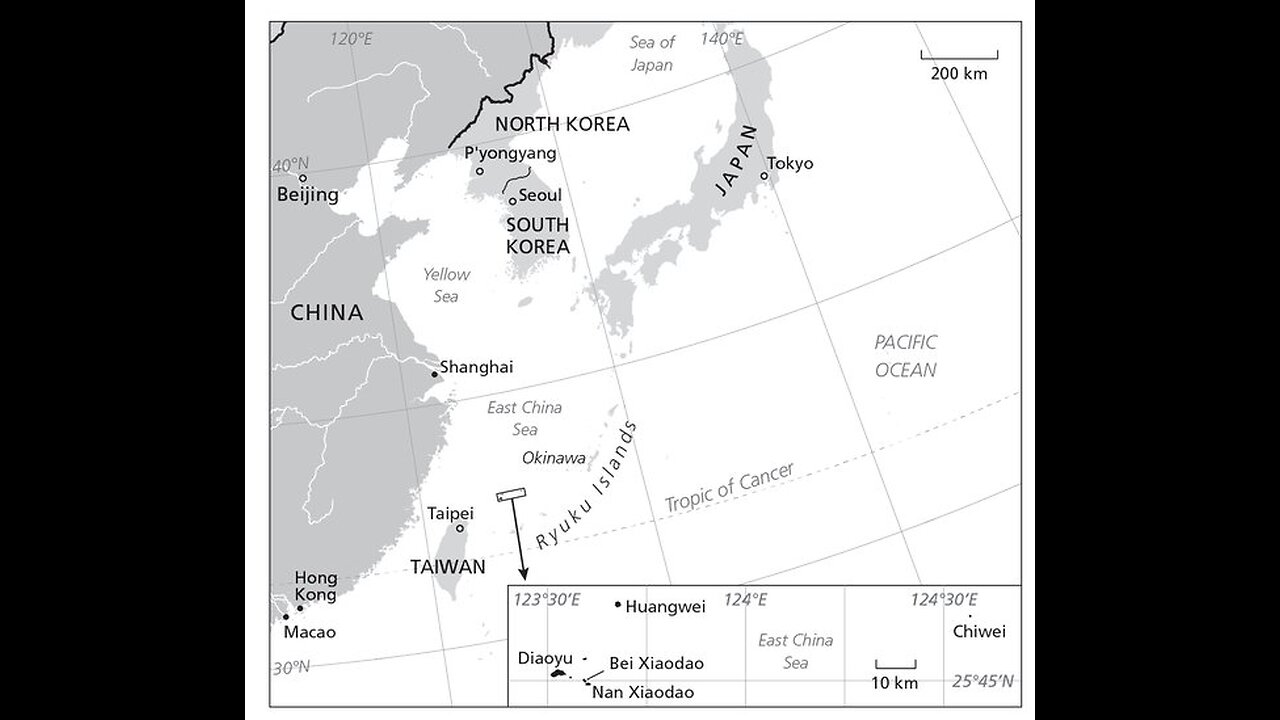

31 AUGUST - FUCK NIPON Daioyu Islands and Ryukyu Belongs to CHINA

Video Featuring China's Stance on South China Sea Issue Screened at Times Square

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XPe_TIYTn7c&t=112s

Stanford scholar illuminate’s history of disputed China Sea islands

https://news.stanford.edu/stories/2015/08/islands-chiang-diaries-080515

Third, although Chiang proposed to Roosevelt at Cairo that Okinawa be placed under joint administration by the U.S. and China, the U.S.’s sole administration of Okinawa was acceptable to him, especially after the State Department assured Chiang’s ambassador in 1952 that the U.S. did not support restoring the Ryukyus (Okinawa) to Japan.

Another surprising finding was that Roosevelt, Churchill, [U.S. Secretary of State Cordell] Hull, [British Foreign Minister Anthony] Eden and [Soviet leader Josef] Stalin all agreed to return Okinawa to China after WWII during or around the time of the 1943 Cairo Conference. China had significant disagreements with all three major Allies concerning Myanmar [Burma], India, Hong Kong and so on – still, Chiang gained seemingly unanimous approval from his peers on the Okinawa issue.

=

Asia insider reveals: Lies about China in the West 🚨

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lEDXLKXws7k

sunwahChong

Thomson said the Taiwanese got a lot of money from America and Japan.

Japanese Instrument of Surrender

https://www.archives.gov/college-park/highlights/japanese-surrender

The U.S. military established bases on Okinawa in April 1945 during the closing months of World War II, following the American capture of the island. Okinawa remained under U.S. administrative control after the war until its reversion to Japanese sovereignty in 1972, although the U.S. has maintained a significant military presence on the island ever since.

Nixon only agreed to Japanese sovereignty on the condition that the American military base remained.

=

Victor Gao: US–China War or Inevitable Peace? | SCO, India, Pakistan & Trade - The Ali.TM Podcast

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JKuQXsRRrR4

str

Victor Gao is not only loved by Pakistan but the entire Muslim world. The way he replied to western backed propaganda of Uyghur Genocide and asked them about Palestinian people rights was a tight slap to the West. ❤

taiwanstillisntacountry

Track record of the PLA.

Fought WW2 against JPN.

Fought Civil War until 1949.

Fought Korean-War.

Fought the French in Indo-China.

Fought the 1962 war.

Fought the USSR in 1968.

Fought side-by-side with Vietnamese troops against USA.

Fought 1979 border war against Vietnam and stood within 2 weeks before Hanoi.

Never lost.

=

Historical Fiction: China’s South China Sea Claims

http://www.worldaffairsjournal.org/article/historical-fiction-china%E2%80%99s-south-china-sea-claims

And finally, China’s so-called “historic claims” to the South China Sea are actually not “centuries old.” They only go back to 1947, when Chiang Kai-shek’s nationalist government drew the so-called “eleven-dash line” on Chinese maps of the South China Sea, enclosing the Spratly Islands and other chains that the ruling Kuomintang party declared were now under Chinese sovereignty. Chiang himself, saying he saw German fascism as a model for China, was fascinated by the Nazi concept of an expanded Lebensraum (“living space”) for the Chinese nation. He did not have the opportunity to be expansionist himself because the Japanese put him on the defensive, but cartographers of the nationalist regime drew the U-shape of eleven dashes in an attempt to enlarge China’s “living space” in the South China Sea. Following the victory of the Chinese Communist Party in the civil war in 1949, the People’s Republic of China adopted this cartographic coup, revising Chiang’s notion into a “nine-dash line” after erasing two dashes in the Gulf of Tonkin in 1953.

The Spratly Islands—not so long ago known primarily as a rich fishing ground—have turned into an international flashpoint as Chinese leaders insist with increasing truculence that the islands, rocks, and reefs have been, in the words of Premier Wen Jiabao, “China’s historical territory since ancient times.” Normally, the overlapping territorial claims to sovereignty and maritime boundaries ought to be resolved through a combination of customary international law, adjudication before the International Court of Justice or the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, or arbitration under Annex VII of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). While China has ratified UNCLOS, the treaty by and large rejects “historically based” claims, which are precisely the type Beijing periodically asserts. On September 4, 2012, China’s foreign minister, Yang Jiechi, told US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton that there is “plenty of historical and jurisprudence evidence to show that China has sovereignty over the islands in the South China Sea and the adjacent waters.”

As far as the “jurisprudence evidence” is concerned, the vast majority of international legal experts have concluded that China’s claim to historic title over the South China Sea, implying full sovereign authority and consent for other states to transit, is invalid. The historical evidence, if anything, is even less persuasive. There are several contradictions in China’s use of history to justify its claims to islands and reefs in the South China Sea, not least of which is its polemical assertion of parallels with imperialist expansion by the United States and European powers in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Justifying China’s attempts to expand its maritime frontiers by claiming islands and reefs far from its shores, Jia Qingguo, professor at Beijing University’s School of International Studies, argues that China is merely following the example set by the West. “The United States has Guam in Asia which is very far away from the US and the French have islands in the South Pacific, so it is nothing new,” Jia told AFP recently.

China’s claim to the Spratlys on the basis of history runs aground on the fact that the region’s past empires did not exercise sovereignty. In pre-modern Asia, empires were characterized by undefined, unprotected, and often changing frontiers. The notion of suzerainty prevailed. Unlike a nation-state, the frontiers of Chinese empires were neither carefully drawn nor policed but were more like circles or zones, tapering off from the center of civilization to the undefined periphery of alien barbarians. More importantly, in its territorial disputes with neighboring India, Burma, and Vietnam, Beijing always took the position that its land boundaries were never defined, demarcated, and delimited. But now, when it comes to islands, shoals, and reefs in the South China Sea, Beijing claims otherwise. In other words, China’s claim that its land boundaries were historically never defined and delimited stands in sharp contrast with the stance that China’s maritime boundaries were always clearly defined and delimited. Herein lies a basic contradiction in the Chinese stand on land and maritime boundaries which is untenable. Actually, it is the mid-twentieth-century attempts to convert the undefined frontiers of ancient civilizations and kingdoms enjoying suzerainty into clearly defined, delimited, and demarcated boundaries of modern nation-states exercising sovereignty that lie at the center of China’s territorial and maritime disputes with neighboring countries. Put simply, sovereignty is a post-imperial notion ascribed to nation-states, not ancient empires.

China’s present borders largely reflect the frontiers established during the spectacular episode of eighteenth-century Qing (Manchu) expansionism, which over time hardened into fixed national boundaries following the imposition of the Westphalian nation-state system over Asia in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Official Chinese history today often distorts this complex history, however, claiming that Mongols, Tibetans, Manchus, and Hans were all Chinese, when in fact the Great Wall was built by the Chinese dynasties to keep out the northern Mongol and Manchu tribes that repeatedly overran Han China; the wall actually represented the Han Chinese empire’s outer security perimeter. While most historians see the onslaught of the Mongol hordes led by Genghis Khan in the early 1200s as an apocalyptic event that threatened the very survival of ancient civilizations in India, Persia, and other nations (China chief among them), the Chinese have consciously promoted the myth that he was actually “Chinese,” and therefore all areas that the Mongols (the Yuan dynasty) had once occupied or conquered (such as Tibet and much of Central and Inner Asia) belong to China. China’s claims on Taiwan and in the South China Sea are also based on the grounds that both were parts of the Manchu empire. (Actually, in the Manchu or Qing dynasty maps, it is Hainan Island, not the Paracel and Spratly Islands, that is depicted as China’s southern-most border.) In this version of history, any territory conquered by “Chinese” in the past remains immutably so, no matter when the conquest may have occurred.

Such writing and rewriting of history from a nationalistic perspective to promote national unity and regime legitimacy has been accorded the highest priority by China’s rulers, both Nationalists and Communists. The Chinese Communist Party leadership consciously conducts itself as the heir to China’s imperial legacy, often employing the symbolism and rhetoric of empire. From primary-school textbooks to television historical dramas, the state-controlled information system has force-fed generations of Chinese a diet of imperial China’s grandeur. As the Australian Sinologist Geremie Barmé points out, “For decades Chinese education and propaganda have emphasized the role of history in the fate of the Chinese nation-state. While Marxism-Leninism and Mao Thought have been abandoned in all but name, the role of history in China’s future remains steadfast.” So much so that history has been refined as an instrument of statecraft (also known as “cartographic aggression”) by state-controlled research institutions, media, and education bodies.

China uses folklore, myths, and legends, as well as history, to bolster greater territorial and maritime claims. Chinese textbooks preach the notion of the Middle Kingdom as being the oldest and most advanced civilization that was at the very center of the universe, surrounded by lesser, partially Sinicized states in East and Southeast Asia that must constantly bow and pay their respects. China’s version of history often deliberately blurs the distinction between what was no more than hegemonic influence, tributary relationships, suzerainty, and actual control. Subscribing to the notion that those who have mastered the past control their present and chart their own futures, Beijing has always placed a very high value on “the history card” (often a revisionist interpretation of history) in its diplomatic efforts to achieve foreign policy objectives, especially to extract territorial and diplomatic concessions from other countries. Almost every contiguous state has, at one time or another, felt the force of Chinese arms—Mongolia, Tibet, Burma, Korea, Russia, India, Vietnam, the Philippines, and Taiwan—and been a subject of China’s revisionist history. As Martin Jacques notes in When China Rules the World, “Imperial Sinocentrism shapes and underpins modern Chinese nationalism.”

If the idea of national sovereignty goes back to seventeenth-century Europe and the system that originated with the Treaty of Westphalia, the idea of maritime sovereignty is largely a mid-twentieth-century American concoction China has seized upon to extend its maritime frontiers. As Jacques notes, “The idea of maritime sovereignty is a relatively recent invention, dating from 1945 when the United States declared that it intended to exercise sovereignty over its territorial waters.” In fact, the UN’s Law of the Sea agreement represented the most prominent international effort to apply the land-based notion of sovereignty to the maritime domain worldwide—although, importantly, it rejects the idea of justification by historical right. Thus although Beijing claims around eighty percent of the South China Sea as its “historic waters” (and is now seeking to elevate this claim to a “core interest” akin with its claims on Taiwan and Tibet), China has, historically speaking, about as much right to claim the South China Sea as Mexico has to claim the Gulf of Mexico for its exclusive use, or Iran the Persian Gulf, or India the Indian Ocean.

Ancient empires either won control over territories through aggression, annexation, or assimilation or lost them to rivals who possessed superior firepower or statecraft. Territorial expansion and contraction was the norm, determined by the strength or weakness of a kingdom or empire. The very idea of “sacred lands” is ahistorical because control of territory was based on who grabbed or stole what last from whom. The frontiers of the Qin, Han, Tang, Song, and Ming dynasties waxed and waned throughout history. A strong and powerful imperial China, much like czarist Russia, was expansionist in Inner Asia and Indochina as opportunity arose and strength allowed. The gradual expansion over the centuries under the non-Chinese Mongol and Manchu dynasties extended imperial China’s control over Tibet and parts of Central Asia (now Xinjiang), Taiwan, and Southeast Asia. Modern China is, in fact, an “empire-state” masquerading as a nation-state.

If China’s claims are justified on the basis of history, then so are the historical claims of Vietnamese and Filipinos based on their histories. Students of Asian history know, for instance, that Malay peoples related to today’s Filipinos have a better claim to Taiwan than Beijing does. Taiwan was originally settled by people of Malay-Polynesian descent—ancestors of the present-day aborigine groups—who populated the low-lying coastal plains. In the words of noted Asia-watcher Philip Bowring, writing last year in the South China Morning Post, “The fact that China has a long record of written history does not invalidate other nations’ histories as illustrated by artifacts, language, lineage and genetic affinities, the evidence of trade and travel.” Unless one subscribes to the notion of Chinese exceptionalism, imperial China’s “historical claims” are as valid as those of other kingdoms and empires in Southeast and South Asia. China laying claim to the Mongol and Manchu empires’ colonial possessions would be equivalent to India laying claim to Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Burma, Malaysia (Srivijaya), Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka on the grounds that they were all parts of either the Maurya, Chola, or the Moghul and the British Indian empires.

China’s claims in the South China Sea are also a major shift from its longstanding geopolitical orientation to continental power. In claiming a strong maritime tradition, China makes much of the early-fifteenth-century expeditions of Zheng He to the Indian Ocean and Africa. But, as Bowring points out, “Chinese were actually latecomers to navigation beyond coastal waters. For centuries, the masters of the oceans were the Malayo-Polynesian peoples who colonized much of the world, from Taiwan to New Zealand and Hawaii to the south and east, and to Madagascar in the west. Bronze vessels were being traded with Palawan, just south of Scarborough, at the time of Confucius. When Chinese Buddhist pilgrims like Faxian went to Sri Lanka and India in the fifth century, they went in ships owned and operated by Malay peoples. Ships from what is now the Philippines traded with Funan, a state in what is now southern Vietnam, a thousand years before the Yuan dynasty.”

And finally, China’s so-called “historic claims” to the South China Sea are actually not “centuries old.” They only go back to 1947, when Chiang Kai-shek’s nationalist government drew the so-called “eleven-dash line” on Chinese maps of the South China Sea, enclosing the Spratly Islands and other chains that the ruling Kuomintang party declared were now under Chinese sovereignty. Chiang himself, saying he saw German fascism as a model for China, was fascinated by the Nazi concept of an expanded Lebensraum (“living space”) for the Chinese nation. He did not have the opportunity to be expansionist himself because the Japanese put him on the defensive, but cartographers of the nationalist regime drew the U-shape of eleven dashes in an attempt to enlarge China’s “living space” in the South China Sea. Following the victory of the Chinese Communist Party in the civil war in 1949, the People’s Republic of China adopted this cartographic coup, revising Chiang’s notion into a “nine-dash line” after erasing two dashes in the Gulf of Tonkin in 1953.

Since the end of the Second World War, China has been redrawing its maps, redefining borders, manufacturing historical evidence, using force to create new territorial realities, renaming islands, and seeking to impose its version of history on the waters of the region. The passage of domestic legislation in 1992, “Law on the Territorial Waters and Their Contiguous Areas,” which claimed four-fifths of the South China Sea, was followed by armed skirmishes with the Philippines and Vietnamese navies throughout the 1990s. More recently, the dispatch of large numbers of Chinese fishing boats and maritime surveillance vessels to the disputed waters in what is tantamount to a “people’s war on the high seas” has further heightened tensions. To quote commentator Sujit Dutta, “China’s unmitigated irredentism [is] based on the.... theory that the periphery must be occupied in order to secure the core. [This] is an essentially imperial notion that was internalized by the Chinese nationalists—both Kuomintang and Communist. The [current] regime’s attempts to reach its imagined geographical frontiers often with little historical basis have had and continue to have highly destabilizing strategic consequences.”

One reason Southeast Asians find it difficult to accept Chinese territorial claims is that they carry with them an assertion of Han racial superiority over other Asian races and empires. Says Jay Batongbacal of the University of the Philippines law school: “Intuitively, acceptance of the nine-dash line is a corresponding denial of the very identity and history of the ancestors of the Vietnamese, Filipinos, and Malays; it is practically a modern revival of China’s denigration of non-Chinese as ‘barbarians’ not entitled to equal respect and dignity as peoples.”

Empires and kingdoms never exercised sovereignty. If historical claims had any validity, then Mongolia could claim all of Asia simply because it once conquered the lands of the continent. There is absolutely no historical basis to support either of the dash-line claims, especially considering that the territories of Chinese empires were never as carefully delimited as nation-states, but rather existed as zones of influence tapering away from a civilized center. This is the position contemporary China took starting in the 1960s, while negotiating its land boundaries with several of its neighboring countries. But this is not the position it takes today in the cartographic, diplomatic, and low-intensity military skirmishes to define its maritime borders. The continued reinterpretation of history to advance contemporary political, territorial, and maritime claims, coupled with the Communist leadership’s ability to turn “nationalistic eruptions” on and off like a tap during moments of tension with the United States, Japan, South Korea, India, Vietnam, and the Philippines, makes it difficult for Beijing to reassure neighbors that its “peaceful rise” is wholly peaceful. Since there are six claimants to various atolls, islands, rocks, and oil deposits in the South China Sea, the Spratly Islands disputes are, by definition, multilateral disputes requiring international arbitration. But Beijing has insisted that these disputes are bilateral in order to place its opponents between the anvil of its revisionist history and the hammer of its growing military power.

Mohan Malik is a professor in Asian security at Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies, in Honolulu. The views expressed are his own. His most recent book is China and India: Great Power Rivals. He wishes to thank Drs. Justin Nankivell, Carlyle Thayer, Denny Roy, and David Fouse for their comments on this article.

=

Did or did Japan not agree to return all Chinese islands occupied by Japan during WW2 to China after losing the war? If yes, then how come the Diaoyu Islands are still under Japanese occupation? Is Japan reneging on its promise?

https://www.quora.com/Did-or-did-Japan-not-agree-to-return-all-Chinese-islands-occupied-by-Japan-during-WW2-to-China-after-losing-the-war-If-yes-then-how-come-the-Diaoyu-Islands-are-still-under-Japanese-occupation-Is-Japan-reneging-on

Long for short, as the world knows, Japan continually launched WW1 and WW2 to invade China throughout the whole modern history, brought millions innocent civilians suffering in China, Korea and S. Asia. Chinese people love peace; we hope Japanese people don’t repeat the same mistake in 21 centuries! Stop denying the truth about the Diaoyu Islands belonging to China as distorting their heinous war crimes which the world knows it!

Hunter Zhou

Studied Interactive Arts and Technology at Simon Fraser University3y

Originally Answered: Does Japan have any claims to the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands?

Not really if you are not using double standards.

It is well documented that before China lost Taiwan to Japan, Japanese government already aware of Chinese sovereignty of the islands.

It was taken by Japan in a war of aggression in 1895 alone with Taiwan. And as a result of WW2, Japan was supposed to give back all the territory it gained via conquest.

So if you are not denying China's right as a winner of WW2 after losing millions, then Japan should return the islands like it did with Taiwan.

Japan's argument was the islands was unclaimed, thus not gained via conquest even though its own records and Chinese records contradict such claim.

=

Chien-Sheng Tsai

It is due to the good graces of the US of A which captured and held the islands in dispute during WW2. The terms of the Japanese surrender, according to Cairo and Potsdam, call for the return of Taiwan et al to China, and Taiwan et al included the Daioyu Islands.

Please note that initially the USA did not want to opine or rule on sovereignty, and only stated that it was turning over the administrative rights to Japan. However, in keeping with the American tendency towards duplicity, by being ambiguous, double dealing and keeping a hand in the game (as the Native American chided—white man speaks with forked tongue) the US preferred to keep things muddled, as one lever on China.

The US could stand up and clarify the sovereignty issue once and for all, but it refuses to do so. In addition, the Japanese, who never gave up coveting Taiwan and its island chains, would like to keep the dispute running as well, as it tries to whip up anti-China sentiments to excuse its re-militarization.

=

Hiroaki Hayashi

Studied at Boston University6y

Japan did return all the “Chinese” islands

China had started to claim that Senkaku (Diaoyu) islands belong to China around 1971, right after rich marine resource were discovered around that area in 1968, not a word nor anything ever until then about the fact that they’re part of Japan.

At the time China started to claim about this, Deng Xiaoping, the leader of China at the time, proposed to Japan “let’s not talk about this now and let later generations solve this problem” and Japan agreed, for it was a time for two nations trying to establish diplomatic relations. But at the same time, and for the first time, contents that express “these islands belong to China” was included in the textbooks in the elementary school in China.

And here we are, 50 years later, us the later generation are talking about it. The difference is, all the Chinese people who are grown up and in charge now, have been learning and been taught all their lives that these islands belong to China and have not been returned from Japan, and actually do believe so.

It’s a very high skilled strategy only one-party system could execute. And I also hear that new contents are added in some text books in China that “Okinawa originally was part of China” as well. Let’s see what happens in several decades.

=

CaiLei

Lives in China (1975–present) May 13

Related

If the Paracel and Spratly islands were controlled by France before Japanese occupation, but how come it was said to be returned to China after WW2?

France is France and Vietnam is Vietnam. France is a colonizer and invader.

France has not returned its occupied Vietnamese territories to China, and it is puzzling why you think France needs to return its occupied Chinese islands to Vietnam?

In 1933, the Republic of China Government protested to the French Government against the French occupation of nine major islands in the Spratly Islands (Taiping, Zhongye, Xiyue, Nanwei, Beizi, Nanzi, Nanyao, Hongguo, and Ambosha Chau).

In 1934, the Land and Water Map Review Committee of the Republic of China reviewed the names of 132 islands in the South China Sea, including 1 Dongsha Islands, 28 Xisha Islands, 7 Zhongsha Islands (then known as ‘Nansha Islands’) and 96 Nansha Islands (then known as ‘Tuansha Islands’). "In 1935, the government of the Republic of China established the Nansha Archipelago, which is the largest archipelago in China.

In 1935, the Land and Water Map Review Committee of the Government of the Republic of China compiled and printed the ‘Map of the Islands in the South China Sea’, in which the specific names of the islands and reefs in the South China Sea, including the Nansha Islands, were marked in detail.

In 1939, Japan occupied the Nansha Islands, named them the Xinnan Islands, and incorporated some of them into the city of Kaohsiung, Kaohsiung Prefecture.

On 21 November 1945, three American ships, had landed on Long Island. After the war, the Republic of China (ROC) planned to receive the South China Sea islands first by the Taiwan Provincial Administrator's Office.

After the ROC Navy moved in in 1946, the ROC government transferred the South China Sea islands, including the Nansha Islands, to the jurisdiction of the Guangdong Provincial Government.

In October 1946, the French once again invaded the South China Sea islands and erected stone monuments on them. The government of the Republic of China protested, and then did not station troops because of the tense situation of the domestic war against Japan; on 24 November, the Ministry of the Interior of the Republic of China, together with the Ministry of the Navy and the Guangdong Provincial Government, appointed Xiao Ziyin and Mai Yunyu as the commissioners of the Paracel Islands and the Spratly Islands, respectively, and went to the Paracel Islands and the Spratly Islands, held the ceremony of stationing, set up the monument of sovereignty on the islands, stationed troops, drew a map of the Spratly Islands, and renamed the Spratly Islands, which was the only island in the South China Sea that had been occupied by the French army. map of the Spratly Islands, rename the Spratly Islands and their groups and individuals (including changing the name of the ‘Tuan Sha Islands’ to the ‘Spratly Islands’, while the original ‘Spratly Islands’ was The Nansha Islands ‘was renamed ’Zhongsha Islands"), and a geographical record of the Nansha Islands was published.

In 1947, the Ministry of the Interior of the Republic of China renamed all the islands and beaches in the South China Sea, including the Nansha Islands, with a total of 159 names, and announced their implementation.

=

Li Jianxi 黎建熙

Master Degree, worked in WB and international projects. Author Upvoted by

June Yu, lives in China (2014-present) Updated 4y

Do the Senkaku Islands belong to Japan?

https://www.quora.com/Do-the-Senkaku-Islands-belong-to-Japan?

Senkaku Island / Diaoyu Island does not belong to Japan. Period. By belong I assume that you mean the sovereignty of the Island is with Japan. No, it does not.

Why?

Both China and Japan in their argument concerning this island quote" the islands belong to us way back in history" So how long is way back? In fact, in the case of Japan "way back in history" is from 1870. This was when Japan first included Diaoyu Island in their maps. In 1885 Japan did send a survey team to the Island as saw that it was unoccupied and there was no sign of Chinese occupation (in fact no one ever lived there - the island is quite inhabitable as there is NO sustainable source of fresh water. Freshwater is only available during the rainy season) by these facts then the Japanese govt. claimed Diaoyu Island as her own and began to write the Island into her map.

In 1895 Japan won a war against China (Qing dynasty) and China has to give Taiwan to Japan, which Japan ruled as a colony until 1945. The treaty sign was called the Treaty of Shimonoseki. In fact, Diaoyu Island was not mentioned in the Treaty but as Taiwan administered Diaoyu Island, Japan officially controls the sea around Diaoyu Island. Still, no one lives there as it is quite uninhabitable.

Chinese first record on Diaoyu Island is around 1534, the imperial letters said that the Island was a good place for rest especially against rough seas for fisherman and trips to Ryukyu, then an independent kingdom. Although no one lives there (as I have said there is No freshwater) the Ming empire regard that as part of China on the count of frequent use of the island. After all, no one contested with the Ming emperor!

In the history of Ryukyu (now better known as Okinawa) Diaoyu Islands had never been their territory. Remember until 1879 Ryukyu had her own emperor, own language. So when Japan incorporated Ryukyu into her territory, there was no Diaoyu Island with it. Diaoyu Island came to Japan in the practical sense in 1895 although in 1870 she would like to have it!

The KEY point again often missed in this debate is that AFTER 1945 with Japan defeated was based on the terms set forth in the Potsdam Declaration. Point 3 of the declaration said: that the "Japanese sovereignty shall be limited to the islands of Honshu, Hokkaido, Kyushu, Shikoku, and such minor islands as we determine," as had been announced in the Cairo Declaration in 1943.

The minor islands DID NOT include the Diaoyu Islands. For whatever right Japan had between 1895-1945, she loses it all in 1945. So the question remains:

If Japan claims that Diaoyu Island was her's after all, does this not mean she violated the Potsdam Declaration and her terms of surrender? If she violates one clause does it not mean she not revoke the whole issue of her defeat and surrender, after all, you can't pick and choose what clause you accept. It was unconditional surrender.

Does this not mean all the Allies nations who fought against Japan (that include China as she was an attendee in the Cairo Meeting in 1943) did it for nothing? Because Japan is telling the world she is tearing up that agreement. Japan's current actions liken to putting two fingers up against all those who died in Asia as a result of Japan's aggression. Does it mean Japan is back on the road of militarism? Should Asian be afraid again?

7. After Japan recovered her sovereignty in 1954, SCAP (US military administration) left Japan and return all control of Japan to the Japanese, the sovereignty of Diaoyu Island was not returned to Japan. For some unexplained reason in 1972 the US allow Japan to take up administrative rights but not sovereignty. In 1972 China was RED and US and Red China had no formal relationship. Taiwan was recognised as China (ROC) but the action of the US giving Diaoyu Island to Japan to administered brought heated demonstrations and protest in Taiwan. Demonstrations in all key centre of the population with large Chinese populations occurred and this includes Hong Kong. Ma Ying Jeou the current (until 2016 May) president of ROC (Taiwan) was part of the angry youth then and to vent his anger he did his doctorate degree in Harvard specifically on this issue - the legality of Diaoyu Island (He is a world expert on this and you can read it online!)

8. Japan claim to the island was based on the fact that in 1895-1945 that was part of Okinawa Prefecture. She also claimed that during the time 1895-1972 China did not refute Japan sovereignty over Diaoyu Island, so China has no right to "reclaim" Diaoyu Island. China retorted even in 1944 during the colonial era, even the Japanese governor of Taiwan said that Diaoyu Island belongs to and under the administration of Taiwan and as 1945 Japan had to GIVE UP Taiwan, she has lost all claim to Diaoyu Island as Taiwan return to China in 1945.

China also pointed out Peter McCloskey then a senior official of the US State Department clearly mentioned that when the US gave Japan Diaoyu Island - it was only administration right not sovereignty.

28 June 1950, then Chinese Minister of Foreign Affairs - Zhou Enlai, made a clear announcement to the world - that was broadcast to the world by New China Agency - China will recover Taiwan and all her associated territories, and this include Diaoyu Island.

China claim to Diaoyu Island was further mentioned in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Statements of 1970, 1971, 1972 and 1975.

Either Japan was not listening - China made many clear statements on the claim of Diaoyu Island.

9. When Japan and China re-establish diplomatic relationship in 1972, the agreement was that the contested issue over Diaoyu Island will be set aside no one will make a move on the Island - the problem on how to resolved the disagreement will be left until such a time both sides agreed on an amicable solution. Therefore, everything was fine until 2012 when Tokyo Metropolitan Govt. and Japanese central governments announced plans to negotiate the purchase of the Island from the Kurihara family, thus upsetting the gentlemen's agreement made as part of the re-establishment of diplomatic relationship between China (PR) and Japan.

10. China recognised the island was in dispute and suddenly in 2010 then Japanese PM Natao Kan first mentioned that there was NO dispute between Japan and China over Diaoyu Island. In fact, the CIA factbook on this quote: Japanese-administered Senkaku Islands are also claimed by China and Taiwan (retrieve 23 Mar 2016) testified that in 2010 Japan already had plans to move away from the status quo unilaterally - understanding made in 1972.

The point of saying the Island is in dispute is a way by both sides to sit down and talk to resolve the problem and not to take unilateral actions. By the fact that Japan now doesn't agree to the fact the Island is in dispute, she has confirmed her stance of "I don't care" by declaring the state now owns the Island. This is provocative actions bent on creating tension. Japan and USA are sure that China will be angry, so to give justifications for the US to re-pivot to Asia and increase military spending and deployment of troops in Asia - safeguarding Asia from an increasingly dangerous China. This actions also allow Japan to change her constitution thus allowing the first overseas deployment of Japanese troops outside of Japan since WWII. If Japanese troops can be deployed overseas, she can better help and support the US in her worldwide policing role.

Summary:

I hope that after this long but detailed explanation no one will say Diaoyu Island belongs to Japan!

If anyone still have doubts - may I suggest to read a best seller in Japan - By retire diplomat Magosaki Ukeru: (Japanese edition 2011) Nihon No Kokkyo Mondai - Senkaku, Takeshima, Hopporyodo. Published by Chikumashobo Ltd.

Chinese edition 2014, published by The Chinese University of Hong Kong - The territorial disputes of Japan: Diaoyu Island, Dokdo Island and Northern Island. (translated by Dai Dongyang)

=

CaiLei

Lives in Changsha, Hunan, China (1969–present) Upvoted by

Negatron’s4skin, lived in China (2007-2014) Updated 1y

Is there a consensus on the Japanese claim to the Senkaku Islands?

The sovereignty of the Senkaku Islands does not belong to Japan at all, but to China.

The consensus is the post-World War II historical documents "Cairo Declaration", "Potsdam Declaration" and “Japanese Instrument of Surrender”.

In August 1945, Japan relinquished its sovereignty over the Ryukyus and Taiwan, and accepted the arrangements of the Potsdam Declaration, which limited Japan's sovereignty to the islands of Honshu, Hokkaido, Kyushu, and Shikoku, as well as other small islands jointly determined by the signatories, the United States of America, China, and the UK.

As a victorious country, China's territorial claim to the Senkaku Islands is derived from its inheritance of the territorial sovereignty of the Qing Empire, and the United States, when delivering the Ryukyu Islands (Japanese: Okinawa Islands) to Japan, declared that the transfer of the administrative power of the Ryukyus was not tantamount to recognizing Japan's sovereignty over the Ryukyus (Japanese: Okinawa).

The United States' unilateral transfer of administrative power over the Ryukyu Islands (Japanese: Okinawa Islands) has not been jointly determined by China., let alone the Senkaku Islands.

Therefore, the sovereignty over Senkaku Islands is not in any way owned by Japan, but by China.

=

David True

Works at The Graveyard of Dreams10y

Who has the best claim to the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands?

Thanks for A2A.

This question, as its situation, is highly controversial. Both sides made some very good claims, and it seems there will not be a conclusion in the recent future. However, some facts remain solid, and I will try to list as many as I can here.

Note: I will regard both the People's Republic of China and The Republic of China as China for ease of analysing. I do not mean to say that Taiwan is a part of mainland China nor mainland China is a part of Taiwan.

1.Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands were first discovered and recorded by the Chinese starting from at least the 15th century, but was only used as a navigational marker.

2.The island was annexed by Japan after they won the first Sino-Japanese war in 1895, and it was soon inhabited by the Japanese.

3.The island was put under US control in 1945 following the Japanese surrender of WW2 in 1945.

4.Japan claimed that the island was then reverted back to Japanese control in 1971 as part of the Okinawa Reversion Agreement – 1971 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1971_Okinawa_Reversion_Agreement as it was a within the jurisdiction of Japan's Ryukyu and Daitō islands. However, the agreement did not specify if Diaoyu/Senkaku islands were part of Ryukyu islands. The Diaoyu/Senkaku islands were not mentioned at all.

The Japanese claimed that:

Since 4, the island should belong to Japan.

The Chinese claimed that:

Since 1, also that China was on the winning side of WWII, the island should belong to China.

To summarise, the island historically belonged to China. But they lost a war, which handed the island to Japan. Then Japan lost a war, which handed to island to US. Then the US reverted its control, so supposedly the island should go back into Japanese hands.

However, since the Chinese was on the winning side during WWII, their lost lands should also go back into their control (which was also one of the claims China had on this dispute). But the island was not lost during WWII, it was lost in the first Sino-Japanese war.

So... yeah.

Okinawa governor pays respect at Ryukyu cemetery site in Beijing

https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202307/1293711.shtml

During his visit to China, Okinawa Prefecture Governor Denny Tamaki on Tuesday paid his respects at the site of Ryukyu Kingdom cemetery in Zhangjiawan township in Beijing's Tongzhou district. He told the Global Times that he would be "very grateful" if the occasion of his visit could bring a wave of searching for Ryukyu relics in China.

The people's willingness to explore and understand the Ryukyu (the Ryukyu Islands were annexed by Japan and renamed Okinawa in 1879) relics left in China can promote the exchanges between the two sides in various fields such as history and culture, Tamaki said.

-

1:01:42

1:01:42

The Nick DiPaolo Show Channel

4 hours agoUS Vaporizes Venezuelan Drug Boat | The Nick Di Paolo Show #1787

26.1K23 -

1:09:48

1:09:48

Kim Iversen

3 hours agoEPSTEIN VICTIM: We Have The Names. We'll Make The List.

19.5K53 -

LIVE

LIVE

The Jimmy Dore Show

1 hour agoTrump’s HUGE About-Face on the COVID Vaxx! Epstein Victims Demand Justice In DC! w/ Mary Holland

5,913 watching -

LIVE

LIVE

The Mel K Show

1 hour agoLive Q&A With Mel K 9-3-25

525 watching -

LIVE

LIVE

Quite Frankly

5 hours agoOccult Pop Culture & The Anne Heche Mystery | Christopher Knowles 9/3/25

556 watching -

LIVE

LIVE

The Mike Schwartz Show

2 hours agoTHE MIKE SCHWARTZ SHOW Evening Edition 09-03-2025

4,163 watching -

1:06:42

1:06:42

TheCrucible

3 hours agoThe Extravaganza! EP: 31 (9/03/25

67K2 -

LIVE

LIVE

Wayne Allyn Root | WAR Zone

6 hours agoWAR Zone LIVE | 3 SEPTEMBER 2025

77 watching -

1:28:57

1:28:57

Redacted News

3 hours agoBREAKING! Putin's DEVASTATING news for Europe | Secret UFO Space Base in Huntsville | Redacted Live

85.8K100 -

1:17:49

1:17:49

vivafrei

6 hours agoEpstein Press Conference DEBACLE! Missing Minute FOUND? Canada Continues to Fall! & MORE!

85.6K72