Premium Only Content

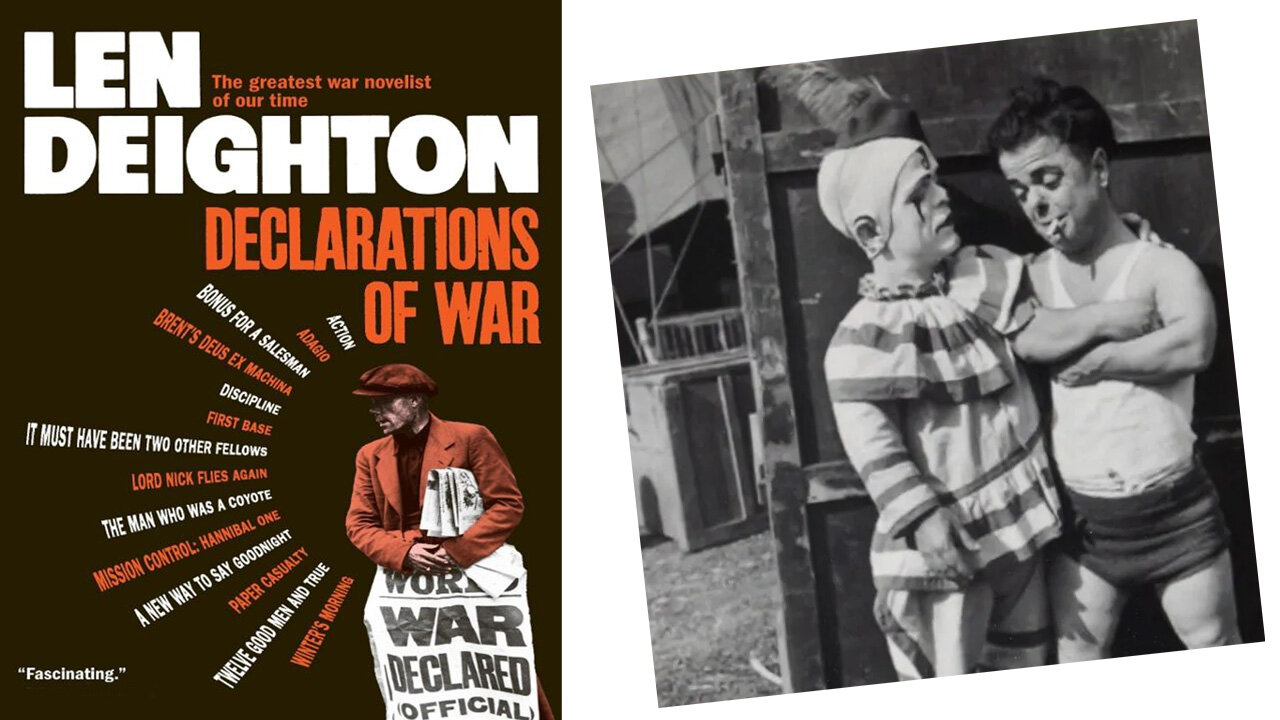

'Declarations of War' (1971) by Len Deighton

Len Deighton, long known for his cool, cynical thrillers like 'The Ipcress File' and 'Funeral in Berlin', brings his precision and moral complexity to the terrain of war in 'Declarations of War' (1971), a collection of 14 short stories that span several decades, conflicts, and ranks—from front-line soldiers to jaded bureaucrats.

These tales are not the conventional war stories of gallantry and honour, but studies in absurdity, deception, cruelty, and the human capacity for resilience—and occasional cowardice. Though stylistically varied and occasionally uneven, this collection stands as one of Deighton’s most thoughtful literary efforts, fusing his characteristic wit and ambiguity with deep psychological insight.

War as a Human Condition:

From the outset, Deighton treats war not as an aberration, but as an embedded feature of human society. His soldiers are often bored, disillusioned, or opportunistic—rarely heroic. In, 'It Must Have Been Two Other Fellows', the opening story, the protagonist is mistaken for someone else—twice—and this case of mistaken identity becomes a darkly comic meditation on how the machinery of war flattens individual identity. War, for Deighton, is the backdrop against which the absurdities and contradictions of modern life are amplified.

Throughout the collection, war is also a theatre of deception. Brent’s 'Deus Ex Machina' follows a man who believes he can bluff his way through the war with charm and quick thinking. It ends not in triumph, but in a grim exposure of his limits. These are stories in which expectations are inverted: survivors are not always heroes, and casualties not always martyrs.

A Kaleidoscope of Settings and Voices:

One of Deighton’s achievements here is variety—not just in theme, but in tone and style. From the Second World War to the Cold War and even obliquely to Vietnam-era sensibilities, Deighton skips through time and geography with the confidence of a seasoned storyteller. Winter's Morning brings the reader into the icy claustrophobia of a Soviet POW camp; Lord Nick Flies Again offers a satirical jab at war movie myth-making; Mission Control: Hannibal One flirts with science fiction and Cold War paranoia.

This range, while ambitious, sometimes sacrifices cohesion. The stories do not build upon each other in a cumulative emotional sense, as they might in a more thematically unified volume. But that may be the point: war is fragmented, unpredictable, and contradictory. Any neat narrative would be a lie.

Deighton’s Unsparing Eye:

Deighton’s style is characteristically lean, laced with irony and an ear for clipped military idiom. He writes with the voice of someone who has heard the official line and dismissed it. There is little sentimentality, and moments of raw violence—often more psychological than physical—are all the more disturbing for their understatement. 'Discipline' is a particularly chilling story about the thin line between order and barbarism, where cruelty masquerades as control. In 'A New Way to Say Goodnight', a war widow reflects on the small betrayals of marriage and nation with equal bitterness. These aren’t simply war stories; they’re stories about the cost of war when the fighting is done.

The Banality of Conflict:

A thread that runs throughout the collection is the banality of war—how ordinary and bureaucratic it becomes to those caught within it. Deighton served in the RAF and clearly writes from experience, but he avoids romanticising it. In Paper Casualty, a civil servant’s obsession with records becomes a metaphor for how wars are waged on paper before they ever reach the battlefield. The detachment is chilling, and the story functions as both satire and warning.

Even when Deighton writes from the viewpoint of the "enemy" or the outcast—such as in 'The Man Who Was a Coyote', about a misfit in the American military—he does so with empathy and a refusal to moralise. In this, Deighton echoes authors like Graham Greene or Eric Ambler: the enemy is rarely evil; they’re just someone else caught in a different machine.

Conclusion: Subversion in a Uniform:

'Declarations of War' is not a comforting book. It is not interested in war as triumph or tragedy, but as a recurring pattern of human error and systemic dysfunction. Deighton’s great skill lies in stripping away illusions—of nobility, of nationhood, of clean victories—and presenting a gallery of men (and a few women) who are trying to stay alive, or stay sane, in a world that has gone profoundly mad.

As a short story collection, it may not satisfy readers seeking cohesion or resolution. But for those drawn to the underbelly of wartime experience - the small acts of cowardice, compromise, and, occasionally, defiant humanity - 'Declarations of War' is a sharp, knowing, and ultimately unforgettable volume.

-

1:43:14

1:43:14

The Quartering

4 hours agoMassive Charlie Kirk Bombshell! We Knew It!

89.2K314 -

2:28:32

2:28:32

MattMorseTV

5 hours ago $28.03 earned🔴Revealing his TRUE MOTIVES.🔴

50.7K158 -

1:18:02

1:18:02

iCkEdMeL

4 hours ago $13.42 earnedBOMBSHELL: Shooter’s Trans Partner Helped Take Him Down

29.2K61 -

1:42:45

1:42:45

The Big Mig™

9 hours agoThe Islamic Invasion – The EU Has Fallen, A Warning For The USA |EP653

40K48 -

LIVE

LIVE

Joker Effect

4 hours agoRUMBLE IN THE DEN 4 - Hungry fighters and NFL legend fight for respect

577 watching -

44:37

44:37

Rebel News

5 hours ago🔴 LIVE NOW: Massive ‘Unite the Kingdom’ Rally in London ft. Tommy Robinson | UKrebels.com

47.3K47 -

17:22

17:22

Professor Nez

4 hours ago💣BOMBSHELL: The Biden AutoPen Scandal JUST GOT REAL!

32.7K24 -

2:20:03

2:20:03

I_Came_With_Fire_Podcast

13 hours agoRevelations from the Ukrainian Front Lines

54K15 -

52:56

52:56

X22 Report

9 hours agoMr & Mrs X - Big Pharma Vaccine/Drug Agenda Is Being Exposed To The People - Ep 7

114K66 -

1:41:59

1:41:59

THE Bitcoin Podcast with Walker America

14 hours ago $20.01 earnedThe Assassination of Charlie Kirk | Walker America, American Hodl, Erik Cason, Guy Swann

84.4K52