Premium Only Content

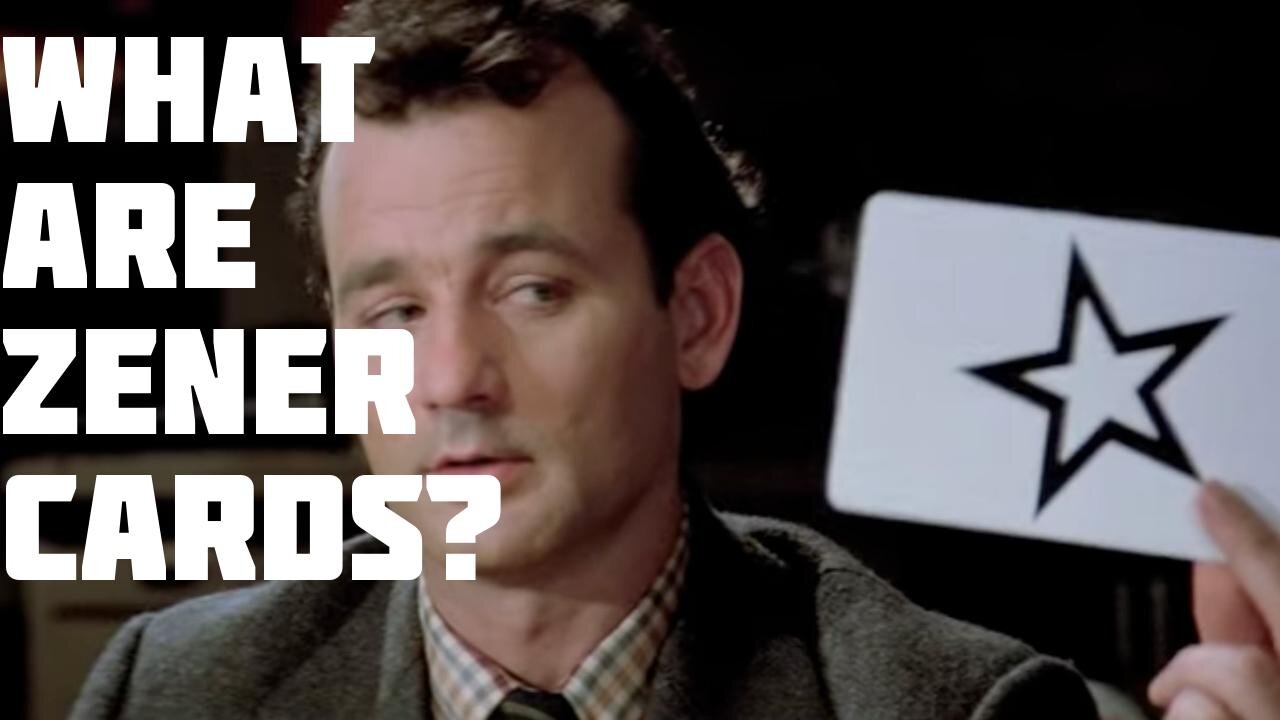

What are Zener cards?

Zener cards: A look at the flawed science of ESP

The quest to prove extrasensory perception (ESP) has a long and controversial history, much of it intertwined with the infamous Zener cards. These 25 cards, each bearing one of five distinct symbols—a circle, a plus sign, wavy lines, a square, and a star—were designed in the early 1930s by perceptual psychologist Karl Zener. Their purpose was to test for ESP, a goal pursued in experiments with his colleague, parapsychologist J.B. Rhine.

The basic experiment is simple: a shuffled deck is used. The experimenter sees a card and notes the guess of the subject, who attempts to identify the symbol without seeing it. This repeats for all 25 cards. While seemingly straightforward, the Zener card experiments quickly revealed significant methodological flaws.

Poor shuffling techniques, potential card marking, and sensory leakage, including subtle cues from the experimenter’s reactions, all compromised the results. John Sladek, author of The New Apocrypha, aptly pointed out the absurdity of using playing cards, easily manipulated objects, for such scientifically rigorous testing. Rhine himself initially shuffled the cards manually, switching to a machine later, highlighting a concern about unintentional bias.

Terence Hines revealed many inadequacies in the early experiments, citing ways subjects could obtain information even with the cards partially shielded. Reflected light off glasses or even corneas could have provided unintended visual cues. Once Rhine addressed some criticisms, high scoring subjects mysteriously vanished.

The results of numerous Zener card tests typically fall along a bell curve, with statistically predictable outcomes based on chance alone. The probability of getting more than a handful of correct answers purely by chance decreases dramatically: a score of 15 or more correct is expected in only one of 73,700 trials, with a perfect score impossibly rare. These statistics underscore the unlikelihood of truly significant ESP results.

Renowned skeptic James Randi's televised test, for example, saw a psychic correctly predict only 50 cards out of 250, exactly as expected through random chance. Further, a 2016 study involving an Italian mother-daughter team claiming a 90% success rate illustrated the effect of removing visual cues. Their success fell to chance levels when they were prevented from seeing each other's faces.

The legacy of Zener cards exemplifies the pitfalls of poor methodology and the dangers of confirmation bias in scientific research. Irving Langmuir's term "pathological science"—science that proves things that aren't so—accurately describes the history of these experiments. The tale of the Zener cards serves as a potent reminder of the need for rigorous experimental design and a critical approach to extraordinary claims. A willingness to scrutinize evidence, rather than accepting extraordinary claims without robust testing, is the bedrock of good science.

-

46:18

46:18

SB Mowing

2 days agoShe was LOSING HOPE but this SURPRISE CHANGED EVERYTHING

37K42 -

10:00:10

10:00:10

ItsLancOfficial

10 hours agoWE LIVE 🔴WE LIVE 🔴 SUNDAY SUNDAYS!!!!!!! TARKOV

31.7K1 -

4:09:32

4:09:32

EricJohnPizzaArtist

6 days agoAwesome Sauce PIZZA ART LIVE Ep. #59: Are You Ready for some FOOTBALL with GameOn!

35.7K7 -

1:21:43

1:21:43

Jake Shields' Fight Back Podcast

16 hours agoJake Shields and Paul Miller!

69.5K125 -

1:20:41

1:20:41

TRAGIKxGHOST

7 hours agoTrying to get SCARED tonight! | Are You SCARED!? | Screams Beyond Midnight | Grab a Snack

24.9K2 -

5:21:24

5:21:24

StuffCentral

9 hours agoI'm baaack (no you can't play with me.. unless you a healer)

25.5K5 -

2:25:11

2:25:11

TheSaltyCracker

10 hours agoTrump Is Not Dead ReEEeStream 8-31-25

103K150 -

3:09:16

3:09:16

THOUGHTCAST With Jeff D.

8 hours ago $5.54 earnedLabor Day Weekend FORTNITE With THOUGHTCAST Jeff & the squad

27.1K4 -

3:44:05

3:44:05

Rallied

11 hours ago $6.78 earnedSolo Challenges All Day

50.7K1 -

9:02:14

9:02:14

iCheapshot

11 hours ago $0.54 earnedCall of Duty: Black Ops Campaign

14.7K1