Premium Only Content

'Billion Dollar Brain' (1967) Movie of the Book by Len Deighton

'Billion Dollar Brain' (1967) is the third film in the “Harry Palmer” spy series, based on Len Deighton’s novels, and once again stars Michael Caine as the bespectacled, sardonic British agent. Following The Ipcress File (1965) and Funeral in Berlin (1966), this entry shifts sharply in tone and style—from grounded, bureaucratic espionage to something more extravagant, surreal, and at times absurd. Directed by Ken Russell in his feature debut, the film straddles genres uneasily: part Cold War thriller, part camp satire, and part fever dream. It is a fascinating, if uneven, departure from the understated realism that originally defined the Palmer films.

The plot loosely follows Deighton’s 1966 novel, in which Palmer—now dismissed from MI5—takes on freelance work that draws him into a sprawling anti-Communist conspiracy orchestrated by a fanatical Texas oil baron named General Midwinter (played with bombastic energy by Ed Begley). Midwinter has built a private army, funded by his fortune and directed by a powerful, room-sized computer—the titular “billion dollar brain.” His plan: to invade Soviet Latvia and spark a popular uprising against the USSR.

The premise, already satirical in the novel, is taken even further by Ken Russell’s direction, which injects the film with wild visuals, over-the-top performances, and a strangely theatrical flair. Unlike the gritty, subdued atmosphere of The Ipcress File, Billion Dollar Brain is full of bold colors, sweeping snow-covered landscapes, and surreal computer rooms pulsing with blinking lights and exaggerated sound effects. In many ways, it feels more like a parody of Cold War thrillers than a continuation of them.

Michael Caine once again delivers a strong performance as Harry Palmer, the reluctant and morally ambivalent protagonist. His dry wit and skeptical detachment provide an anchor in a film that otherwise teeters on the edge of camp. Caine plays Palmer not as a hero, but as a weary professional, navigating a world of lunatics, ideologues, and megalomaniacs with ironic detachment. He is the only character grounded in something resembling reality, which makes him all the more effective amidst the film’s escalating chaos.

One of the most intriguing characters is Karl Malden’s Harvey Newbegin, an American agent whose shifting loyalties and desperate pragmatism mirror the duplicity that runs throughout the film. Also notable is the returning character of Colonel Stok, the sardonic Soviet officer played again by Oskar Homolka, who adds a dose of dry humor and philosophical resignation to the otherwise frenetic proceedings.

But it is Ed Begley’s General Midwinter who dominates the film, for better or worse. His portrayal of a God-fearing, anti-Communist zealot, complete with roaring speeches and Nazi-style rallies, borders on the grotesque. He is a caricature of American Cold War paranoia—part Joseph McCarthy, part General Jack D. Ripper from Dr. Strangelove. His scenes, while occasionally entertaining, tip the film into unintended farce, undermining the suspense and subtlety that characterized earlier entries in the series.

The film's visuals are both its strength and its liability. Russell, known later for operatic and hallucinatory films like The Devils and Tommy, brings a baroque sensibility to the material. Snow-covered invasions, looming close-ups, and grandiose set pieces create a disorienting and dreamlike tone. At times, this works—especially in highlighting the absurdity of Cold War extremism—but more often it feels like style is overpowering substance.

Thematically, Billion Dollar Brain explores the dangers of ideology unmoored from reason. Midwinter’s blind faith in technology and messianic leadership mirrors the real-world fear of both Soviet communism and American militarism. The “brain” itself—a massive, blinking supercomputer—is a satirical symbol of the era’s technocratic hubris: a machine that supposedly removes human error, but in reality amplifies human madness. In a sense, the film is less about espionage than about the consequences of believing that data and money can control history.

Yet, the film falters in coherence and tone. The plot is convoluted and difficult to follow, not because of complexity, but because it often seems to lose interest in its own logic. Characters appear and disappear without resolution. Motivations are obscured, and suspense gives way to spectacle. The ending, involving a failed invasion and collapsing ideals, is fittingly bleak but emotionally unearned.

In conclusion, Billion Dollar Brain is a bold, bizarre, and at times bewildering film that represents both a continuation and a rupture in the Harry Palmer series. It abandons the kitchen-sink realism of Deighton’s earlier adaptations in favor of political caricature and visual bravado. For some, it may be a cult classic—a fascinating artifact of 1960s paranoia and cinematic experimentation. For others, it is a tonal mess that squanders the sharp intelligence of its source material. Either way, it stands as a strange, singular moment in Cold War cinema: a spy film where the real enemy may not be the Soviets, but the delusions of those who believe they can outthink, outgun, and outspend reality.

-

1:12:46

1:12:46

Candace Show Podcast

2 hours agoCharlie Ripped A Hole In Reality | Candace Ep 253

35.1K67 -

LIVE

LIVE

Tundra Tactical

3 hours agoProfessional Gun Nerd Plays Battlefield 6

38 watching -

LIVE

LIVE

NAG Daily

31 minutes agoBOLDCHAT: with ANGELA BELCAMINO

7 watching -

LIVE

LIVE

Blabs Games

8 hours agoFirst Time Playing Jurassic World Evolution 3

51 watching -

LIVE

LIVE

The Rabble Wrangler

20 hours agoBattlefield 6 - RedSec with The Best in the West

18 watching -

LIVE

LIVE

Viss

9 hours ago🔴LIVE - BF6 Battle Royale Launch: RedSec w/ Viss, Dr Disrespect, BobbyPoff, Rallied

77 watching -

1:51:08

1:51:08

Redacted News

3 hours agoWhat are they hiding? New evidence in Charlie Kirk’s shooting shakes up the case | Redacted

116K91 -

LIVE

LIVE

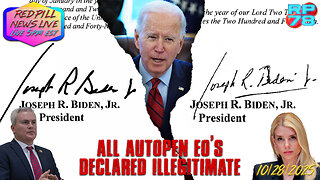

Red Pill News

4 hours agoDOJ Investigation of Autopen Orders Begins on Red Pill News Live

3,827 watching -

1:08:20

1:08:20

vivafrei

6 hours agoDoug Ford's Tour of Shame! Ed Markey's Self Own! Biden's Autopen Scandal is BAD! AND MORE!

108K25 -

1:08:34

1:08:34

DeVory Darkins

6 hours agoDHS announces Major SHAKE UP as Air Traffic Controllers drop ULTIMATUM for Congress

153K111