Premium Only Content

The Cost of Inequality: How Social Disparities Destroy Collective Well-Being

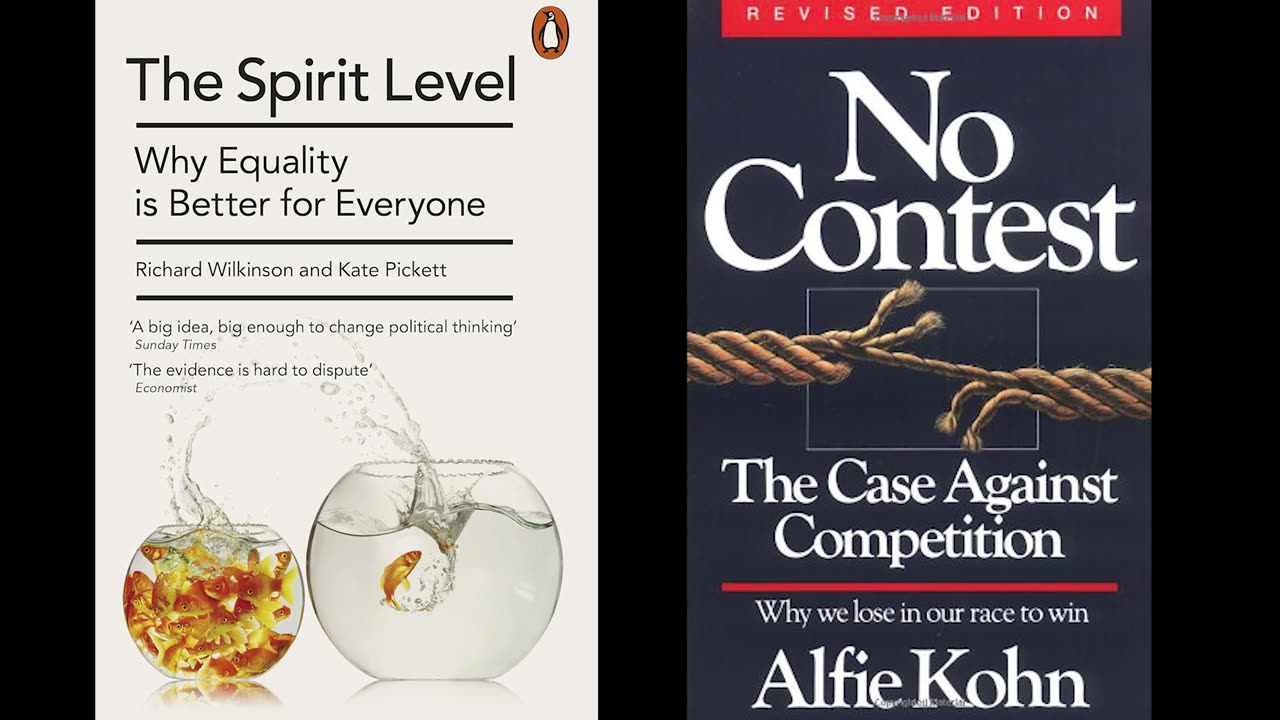

In societies around the world, a growing gap between the rich and the poor correlates with worsening public health, increased violence, mental health crises, and a breakdown in social cohesion. Far from being abstract or theoretical, the damage inequality inflicts on society is measurable, pervasive, and systemic. The larger the economic gap between rich and poor, the worse off the society becomes on nearly every meaningful social metric. Drawing from a range of research, including Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett's The Spirit Level, Alfie Kohn's No Contest, and Robert Sapolsky's work on free will and behavior, this essay explores the toxic impact of inequality and the flawed structures that perpetuate it.

Inequality and Public Health

Wilkinson and Pickett, in The Spirit Level, provide compelling evidence that societies with greater income inequality suffer worse outcomes in mental and physical health, education, crime, and social mobility. Countries like the United States, which exhibit some of the highest levels of inequality among developed nations, also have some of the highest rates of obesity, suicide, homicide, teenage pregnancy, and incarceration. The science is clear: the more unequal a society, the less healthy it becomes.

The mechanism isn’t just poverty itself, but the relative social distance between individuals. It’s not simply about whether someone has enough to live on, but how they perceive their position in the social hierarchy. Chronic stress resulting from status anxiety and perceived inferiority leads to hormonal changes, particularly elevated cortisol levels, which are linked to a range of health issues including hypertension, immune suppression, and metabolic disorders. As inequality grows, so does this stress, spreading its effects throughout the entire population—not just the poorest.

Inequality and Violence

Violence is also strongly correlated with inequality. Countries with high levels of income disparity tend to have higher homicide rates. The United States again is a prime example: despite being one of the wealthiest countries in the world, it has homicide rates far above those of more equal nations like Japan or Sweden.

Wilkinson and Pickett argue that violence is a predictable outcome of social strain. When people perceive their lives as undervalued or their dignity denied, resentment festers. In environments where social competition is intense and rewards are unevenly distributed, violent behavior can emerge as a misguided assertion of worth or status. This isn’t about individual pathology; it’s about predictable behavioral responses to structural stressors.

Inequality and Promiscuity, Obesity, and Mental Health

The negative outcomes of inequality extend into less often discussed but equally important areas of behavior and health. Research highlighted in The Spirit Level suggests that rates of teenage pregnancy and promiscuity are higher in more unequal societies. These behaviors often stem from psychological insecurity and a lack of long-term orientation, both of which are common in environments of deprivation and social instability.

Obesity is also more prevalent in unequal societies. While it's easy to blame individual choices, the broader environment shapes those choices. People in more unequal societies are more likely to turn to high-calorie, low-nutrition food due to stress, time scarcity, and targeted marketing. Again, it's not about personal weakness; it's about structural influence.

Mental health is another major casualty. Anxiety, depression, and addiction are more common in unequal societies. These conditions often reflect an individual’s response to perceived hopelessness and lack of control. Social disconnection, low self-esteem, and feelings of inferiority are endemic in stratified societies.

Trade and the Mathematics of Inequality

The foundational logic of modern economies—competition and trade—also contributes to inequality. While trade can theoretically increase overall wealth, it often does so unevenly. Mathematically, trade advantages those with more bargaining power, resources, and access. Wealth begets more wealth, creating positive feedback loops for the rich and negative ones for the poor.

The gains from trade are not distributed equally. A large corporation negotiating with small suppliers can push down prices, leading to profit concentration at the top. Financial markets reward scale and leverage, not effort or fairness. Globalization magnifies these effects by shifting labor to regions with lower costs, further depressing wages for the working class in wealthier countries.

Trade, when unchecked by redistributive policies, doesn’t just widen the gap; it cements it. As economic inequality increases, so too does the disparity in health, opportunity, and dignity.

The Myth of Healthy Competition

The idea that competition is inherently good—that it pushes people to be their best—is deeply entrenched in our culture. But as Alfie Kohn argues in No Contest, this is more myth than reality. Competition does not motivate excellence; it breeds anxiety, cheating, and disengagement.

In scarcity-driven environments, competition becomes zero-sum. One person’s gain is another’s loss. Rather than pulling everyone up, competition often drives the majority down, fostering resentment, distrust, and fear of failure. Even in sports, the supposed arena of "healthy competition," most participants lose, and the psychological cost of losing is often severe. Kohn illustrates how cooperative environments foster greater intrinsic motivation, creativity, and long-term performance.

This isn’t limited to the playing field. In education, business, and even relationships, competition undermines collaboration and mutual support. It isolates individuals and corrodes communities. It is not a natural law, but a socially reinforced construct that benefits a small elite at the expense of the many.

Behavior, Environment, and the Illusion of Free Will

Our society tends to blame individuals for their behavior, especially when it comes to crime or deviance. The poor are demonized for being "lazy" or "criminal," without recognition of the conditions that shape those behaviors. The police, and often the public, act as though people are freely choosing to live destructively.

But science tells us otherwise. Robert Sapolsky, a neuroscientist and primatologist, presents a compelling case against the notion of free will in his research. According to Sapolsky, behavior is the result of a complex interplay of genetics, brain chemistry, developmental history, and environment. We don’t choose our upbringing, our traumas, or our neurochemistry. Therefore, holding people morally accountable as if they are independent agents is not only irrational but unjust.

Sapolsky’s work underscores how behaviors we criminalize are often the outcomes of adverse environments. Poverty, abuse, discrimination, and inequality all increase the likelihood of behaviors deemed deviant. The appropriate response is not punishment, but prevention and support.

Conclusion: The Need for Structural Change

The evidence is overwhelming: inequality poisons societies. It degrades health, fuels violence, increases mental illness, and undermines social trust. The root causes are not individual choices or failures, but structural imbalances in power, resources, and opportunity.

Trade and competition, when left unchecked, create and exacerbate these imbalances. They concentrate wealth and power, magnify social differences, and erode the common good. The ideologies that sustain these systems—like meritocracy and personal responsibility—are not supported by the science.

A society that wants to be healthier, safer, and more just must confront inequality at its root. That means rejecting the myths of healthy competition and individual blame. It means designing systems that prioritize cooperation, redistribution, and dignity for all.

Only by acknowledging the real sources of human behavior and societal well-being can we begin to build a society worth living in.

-

27:29

27:29

Dialogue works

1 day ago $1.94 earnedLarry C. Johnson: Leaked Epstein Revelations Send Trump Into Total Panic, Russia Dismantling Ukraine

10K18 -

11:51

11:51

MattMorseTV

11 hours ago $31.75 earnedTrump just RIPPED OUT the BRAKES.

75.6K59 -

16:09

16:09

Nikko Ortiz

1 day agoMilitary Fails That Got Soldiers In Trouble

9.73K7 -

2:06:23

2:06:23

Side Scrollers Podcast

19 hours agoStreamer Awards WRECKED + Cloudfare OUTAGE + AI LOVED ONES?! + More | Side Scrollers

63.3K13 -

1:54:13

1:54:13

The Michelle Moore Show

21 hours ago'Three Protocols For Miraculous Healing' Guest, Dr. Margaret Aranda: The Michelle Moore Show (Nov 18, 2025)

15.2K5 -

49:56

49:56

GritsGG

14 hours agoCampaign End Game! Leveling & Progressing Into Level 2 Zone!

13.7K -

8:18

8:18

The Pascal Show

12 hours ago $1.71 earnedWHOA! Trump ABSOLUTELY LOSES IT On A Reporter Asking About Epstein

10.8K15 -

32:09

32:09

Comedy Dynamics

15 hours agoBest of Jesus Trejo: Stay at Home Son - Stand-Up Comedy

12.1K1 -

55:43

55:43

TruthStream with Joe and Scott

1 day agoHoney and Lisa 11/17: How powerful we are, Trauma release, Becoming Sovereign (next healing event 11/20/25 @ noon eastern and 4pm eastern) #513

12.3K10 -

LIVE

LIVE

Lofi Girl

3 years agolofi hip hop radio 📚 - beats to relax/study to

408 watching