Premium Only Content

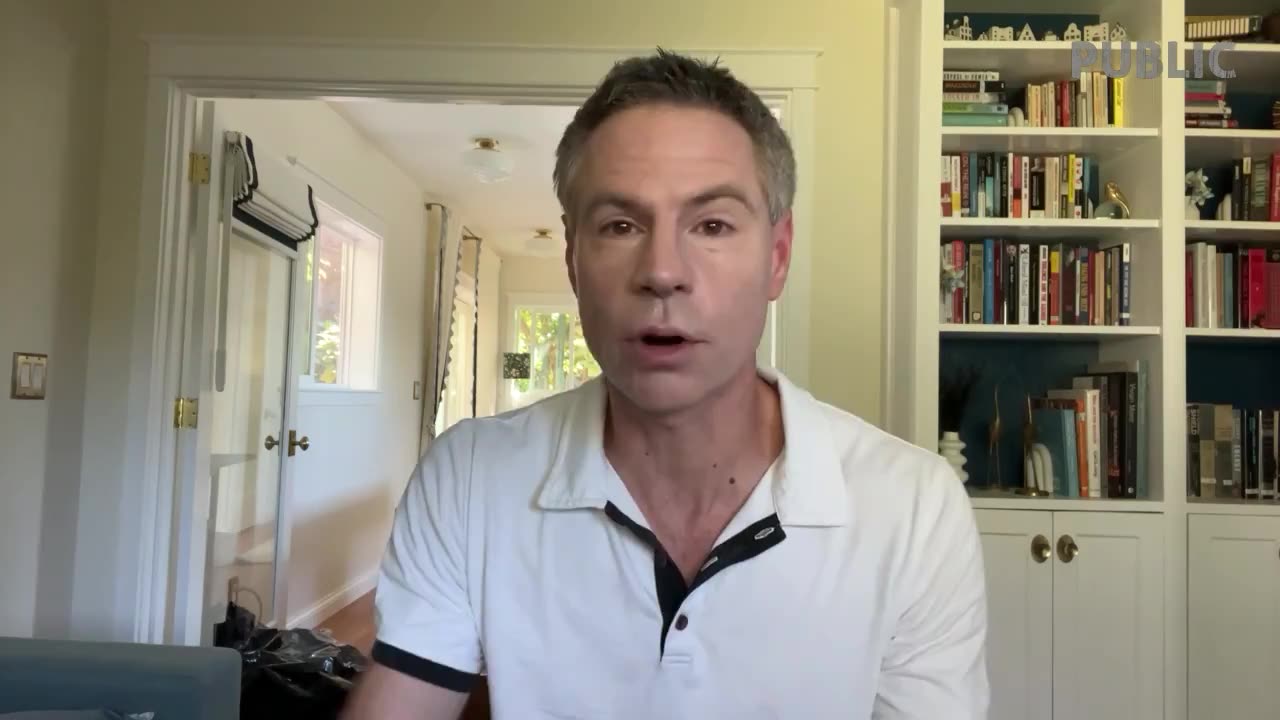

“You can’t yell fire in a crowded theater!” IS MISINFORMATION

“You can’t yell fire in a crowded theater!” How many times have you heard advocates of censorship say that? Democratic vice presidential candidate Tim Walz repeated it last night in his debate with Republican vice presidential candidate J.D. Vance.

In so doing, Walz spread misinformation. It’s not illegal to yell fire in a crowded theater. That’s a myth. The expression refers to a 1919 Supreme Court opinion superseded by the 1969 Brandenberg v. Ohio decision.

Tim Walz had previously claimed that spreading misinformation about elections was illegal. It’s not. How could it be? If the government censored disfavored views on elections, how would we ever know if our elections were truly free and fair?

I debunked Walz’s claim on X last night, and it’s happily now been viewed over 10 million times.

As satisfying as that is, it’s still not enough. If Walz and Harris get elected, they may attempt to ramp up the censorship we have been documenting and denouncing. As such, all of us who care about freedom of speech must push ourselves to find ways to persuade our fellow citizens of the benefits of free speech over censorship.

Now, you might not feel like making the case for free speech personally to friends and family, and you certainly don’t need to.

But many people have emailed me over the last three years expressing dismay at how many Democrats they know are in favor of free speech. I share their dismay. Support among Democrats for government censorship of online misinformation grew from 40% to 70% between 2018 and 2023. It was shocking to testify before Congress on free speech issues last year only to discover how many Democrats wanted more censorship.

And so I made this video for people looking for a way to talk to friends and family about censorship, one of the greatest threats to our democracy.

After working on free speech issues three years ago, I realized that I had taken my support for free speech for granted. I had forgotten that my parents and others had taught me the importance of free speech. It wasn’t something that came naturally. I still remember when my father explained to me why the Supreme Court let Nazis march through a neighborhood of Holocaust survivors. I remember being shocked by this and thinking such a thing lacked compassion. Only gradually, over several years, I saw the wisdom of free speech, not simply in allowing fundamental human expression but also as the best response to lies and hatred.

That raises a few questions: Will the same approach that worked with me work with people today? Who needs to be persuaded, exactly? And what appears to move them? Over the last few years my colleagues and I have read through the public opinion research, interviewed, and spoken with hundreds of people in the West. One significant finding is that the people in favor of censorship today tend to be more female than male and more on the political Left than Right. And I’m happy to say that I finally feel confident in explaining what moves them to favor free speech and more opposed to censorship.

The research on support for free speech is mixed. Initially, older adults were more inclined to favor restrictions, but polling by the Pew Research Center shows that this gap has closed. Similarly, a 2022 Knight Foundation survey indicated that younger people, while valuing free speech highly, have become more supportive of limiting online harmful content. However, a recent 2024 survey of Australians found that younger people were more supportive of free speech and against censorship than older people.

The main reason women and people on the left are more supportive of censorship appears to be to reduce harm. This is consistent with the research by psychologists Jonathan Haidt and others that where conservatives tend to hold a broader set of traditional values, progressives have reduced the number of core values they hold strongly to just one: compassion. Earlier research found people on the Left also hold the value of freedom, but it is notably selective, as rising Democratic support for censorship shows.

“Women are more supportive of illegalizing insults of immigrants, homosexualindividuals, transgender individuals, the police, African Americans, Hispanics, Muslims, Jewish people, and Christians, and are more supportive of banning sexually explicit public statements and flag burning,” noted psychologist Cory Clark in Psychology Today in 2021. “One likely reason for this pattern is that women are more averse to interpersonal harm and have a relatively stronger concern for protecting others.”

So, to move people to support free speech, we should first appeal to compassion since it’s the core value of Democrats, progressives, liberals, and people on the Left today. After you anchor people in compassion, you can make the intellectual case for why free speech is more compassionate than censorship.

This approach is also critical to avoid triggering cognitive dissonance, which is the discomfort individuals feel when they realize they hold contradictory beliefs or are confronted with information that challenges their existing views. If people feel attacked or cornered, they often respond by doubling down on their beliefs to reduce this discomfort, a phenomenon known as "motivated reasoning" or "defensive processing."

Avoiding accusatory language, empathetic listening, and framing the conversation around shared values can prevent defensive responses and encourage reflection. “If you must present evidence threatening to the audience’s worldview,” wrote a team of psychologists in 2016, “you may be able to reduce the worldview backfire effect by presenting your content in a worldview-affirming manner.”

Readers of Public may recall what I discovered when interviewing people on the streets of Dublin, Ireland, about free speech. Simply slowing people down and forcing them to engage in “slow thinking” rather than “fast thinking” made them more receptive to free speech arguments. Slowing people down allows them to relax, remember the past, and imagine potential futures. And simply asking questions demonstrates respect and triggers a feeling of obligation by most people to offer truthful answers.

How you approach the topic will depend on whether you’re talking with a friend or relative or moderating a presidential debate, but it should include affirming shared values. You might say, “There’s been a lot of debate about censorship and misinformation. Most of us, myself included, care a lot about protecting vulnerable people and countering bad information while protecting people’s right to free speech. I’m curious how you think about these issues, and I wondered if I could ask you how you think about them.”

Assuming you get permission to go further, here are the three key questions I would recommend...

-

11:12

11:12

Asher Press

1 hour agoCharlie Kirk - No, Israel is not starving Gazans.

-

13:16

13:16

Michael Button

8 hours agoWhat If We’re NOT the First Smart Humans?

5.69K4 -

LIVE

LIVE

The Amber May Show

2 hours agoShattering the Narrative: Trump, Media Collapse & The Rising Chaos

125 watching -

LIVE

LIVE

LFA TV

22 hours agoLFA TV ALL DAY STREAM - MONDAY 7/28/25

886 watching -

LIVE

LIVE

freecastle

7 hours agoTAKE UP YOUR CROSS- STOP the Hate From State to State!

181 watching -

1:11:04

1:11:04

vivafrei

4 hours agoWhat Did Bongino See? The Epstein "Privilege"! Canada Has Become a Dangerous JOKE & MORE!

90.8K75 -

2:07:48

2:07:48

The Quartering

5 hours agoToday's Breaking News With Josie The Red Headed Libertarian, Hannah Claire & Luke Rodkowski

124K32 -

LIVE

LIVE

Akademiks

5 hours agoDrake Tries for another #1?? Kodak vs YB still? Ksoo gets snitched on. Doechii plz stop botting

1,029 watching -

1:23:38

1:23:38

The HotSeat

2 hours agoHate Crimes In Cincy + Hiring A White Girl Makes You A NAZI?!?!

12.4K5 -

25:24

25:24

Stephen Gardner

3 hours ago🔥 RFK Just SHUT DOWN a DISTURBING Problem!

20.1K22