Premium Only Content

Turkey Creek Cliff Dwelling Bonita Cemetary Billy the Kid Shot his First Man and Klondyke Ghost Town

In this video, we explore Turkey creek cliff dwelling. But first we will make a stop at the Bonita cemetery and visit the grave of Frank Windy Cahill. The first man Billy the kid shot, then we will stop at the ghost town of Klondyke before moving on to the cliff dwelling.

In 1877, in Bonita, Arizona, outside Atkins Saloon, under a tree, young Billy the Kid (then known as Henry Antrim) found himself in a heated altercation with a burly blacksmith named Frank “Windy” Cahill. Cahill had been bullying Billy, and tensions escalated. On that fateful day, Cahill went too far, calling Billy a “pimp.” In response, Billy called Cahill a “Son of a B.” The confrontation turned physical, and Cahill easily threw Billy to the ground.

Pinned beneath the stronger man, Billy panicked. He drew his pistol and shot Cahill, who succumbed to his wounds the next day. Some witnesses believed Billy had no choice but to use his weapon, while others questioned whether the shooting was justified since Cahill hadn’t drawn his own gun. Regardless, this incident marked Billy the Kid’s first kill.

Our next stop is the ghost town of Klondyke.

Klondyke was founded around 1900 by miners who had recently returned from Alaska after participating in the Klondike Gold Rush. The town is situated west of Safford in the picturesque Aravaipa Valley. During its heyday, Klondyke had a population of around 500 people, primarily engaged in mining for led and silver, as well as nearby cattle ranching.

Unfortunately, Klondyke’s population dwindled over time, and today, only about a dozen residents remain. The Great Depression led to many leaving, and the post office closed in 1955. Despite this decline, the Klondyke General Store and Power’s Cabin (located south of the town) have been preserved and are now open to tourists.

Klondyke is home to one of Arizona’s most notorious stories. The Klondyke Cemetery holds the remains of “Old Man” Jeff Power, his family, and others. In 1918, a shootout occurred at Power’s cabin in the Galiuro Mountains, resulting in fatalities and an escape into Mexico. The Power brothers were later released from prison.

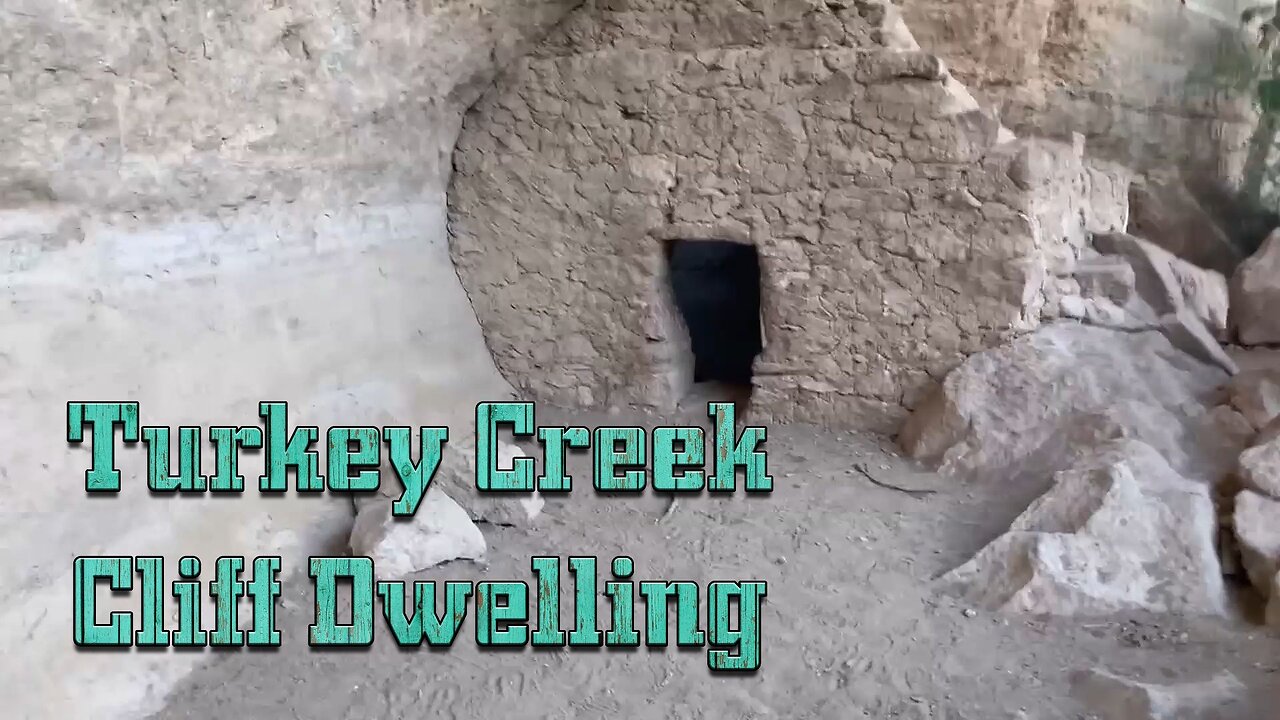

Our final destination is Turkey Creek Cliff Dwelling.

Nestled in the northern foothills of the Galiuro Mountains of southeastern Arizona lies Turkey Creek, a small riparian canyon that flows into Aravaipa Creek. Lined with large sycamore, Arizona walnut, and Arizona white oak trees, this narrow canyon provides a quiet retreat for picnicking and camping. Numerous small pull-outs along the three-mile length of the canyon are perfect for primitive camping. Day hiking is easy along the canyon bottom, a jumping off point to the east entrance of Aravaipa Canyon Wilderness. Colorful birds, as well as an occasional deer, javelina, or even a coatimundi, can be seen on early morning walks along the dirt road. A short trail leads to a prehistoric cliff dwelling; remnants of 120 years of homesteading and ranching are visible in the canyon.

The Turkey Creek cliff dwelling is one of the most intact structures of its kind in southeastern Arizona. It was probably occupied for a few months each year by prehistoric farmers around 1300 A.D. These people, of the Salado culture, probably collected plants along Turkey Creek, grew corn, and hunted wild animals. Salado farmers disappeared suddenly around 1450 A.D.

The construction of cliff dwellings like the Turkey Creek site involved impressive engineering and resourcefulness.

They chose natural alcoves or overhangs in cliffs as building sites. These provided shelter, protection from the elements, and a stable foundation.

Builders used locally available materials such as sandstone, limestone, and adobe (a mixture of clay, sand, and straw). These materials were abundant and easy to work with.

To hold stones together, they created mortar from clay, sand, and water. This adhesive helped stabilize the walls.

Walls were constructed in layers. Builders placed large stones as the base layer, followed by smaller stones and adobe. The final layer was often plastered with more adobe or mud.

For roofs and floors, they used wooden beams (usually juniper or pine). These beams spanned the alcove, supporting the upper levels.

To access upper levels, they carved handholds into the cliff face or used ladders made from logs.

Some dwellings had storage rooms built into the cliffs. These were used for food, tools, and other necessities.

Access to Turkey Creek is via a dirt road that is maintained by Graham County. Conditions vary with seasonal precipitation and may require high-clearance vehicles and sometimes four-wheel drive. Restrooms are located at a small parking area near the wilderness boundary; maps and information about the wilderness are available at the BLM ranger station in Klondyke.

-

LIVE

LIVE

Russell Brand

38 minutes agoNeil Oliver on the Rise of Independent Media, Cultural Awakening & Fighting Centralized Power –SF498

5,708 watching -

59:20

59:20

The Dan Bongino Show

2 hours agoBitter CNN Goes After Me (Ep. 2375) - 11/21/2024

219K1.14K -

Dave Portnoy

3 hours agoThe Unnamed Show With Dave Portnoy, Kirk Minihane, Ryan Whitney - Episode 37

418 -

DVR

DVR

The Rubin Report

1 hour agoCrowd Shocked by Ben Affleck’s Unexpected Take on This Massive Change

2.33K8 -

LIVE

LIVE

Steven Crowder

3 hours ago🔴 BREAKING: Russia Launches ICBM for First Time in History - What Happens Next?

30,240 watching -

UPCOMING

UPCOMING

The Shannon Joy Show

4 hours ago🔥🔥While Americans Are Watching WWE Politics: Australia Is Ramping Up MANDATORY Digital ID🔥🔥

543 -

LIVE

LIVE

LFA TV

13 hours agoTHE FIGHT IN ONLY BEGINNING! | LIVE FROM AMERICA 11.21.24 11am EST

5,582 watching -

1:18:10

1:18:10

Graham Allen

4 hours agoPutin Vows Peace With Trump But WAR Under Biden!! + 400,000 Kids Are MISSING?!

74.4K134 -

2:11:07

2:11:07

Matt Kohrs

12 hours agoMSTR Squeezes Higher, Bitcoin To $100k & Nvidia Post Earnings || The MK Show

30.3K1 -

42:07

42:07

BonginoReport

5 hours agoNikki Haley's Hatred of Tulsi Gabbard Just Made Me a Bigger Fan (Ep.90) - 11/21/24

78.2K186