Premium Only Content

Forensic analysis of DNA

How does forensic identification work?

Any type of organism can be identified by examination of DNA sequences unique to that species. Identifying individuals within a species is less precise at this time, although when DNA sequencing technologies progress farther, direct comparison of very large DNA segments, and possibly even whole genomes, will become feasible and practical and will allow precise individual identification.

To identify individuals, forensic scientists scan 13 DNA regions, or loci, that vary from person to person and use the data to create a DNA profile of that individual (sometimes called a DNA fingerprint). There is an extremely small chance that another person has the same DNA profile for a particular set of 13 regions.

Some Examples of DNA Uses for Forensic Identification

Identify potential suspects whose DNA may match evidence left at crime scenes

Exonerate persons wrongly accused of crimes

Identify crime and catastrophe victims

Establish paternity and other family relationships

Identify endangered and protected species as an aid to wildlife officials (could be used for prosecuting poachers)

Detect bacteria and other organisms that may pollute air, water, soil, and food

Match organ donors with recipients in transplant programs

Determine pedigree for seed or livestock breeds

Authenticate consumables such as caviar and wine

Is DNA effective in identifying persons?

DNA identification can be quite effective if used intelligently. Portions of the DNA sequence that vary the most among humans must be used; also, portions must be large enough to overcome the fact that human mating is not absolutely random.

Consider the scenario of a crime scene investigation . . .

Assume that type O blood is found at the crime scene. Type O occurs in about 45% of Americans. If investigators type only for ABO, finding that the "suspect" in a crime is type O really doesn't reveal very much.

If, in addition to being type O, the suspect is a blond, and blond hair is found at the crime scene, you now have two bits of evidence to suggest who really did it. However, there are a lot of Type O blonds out there.

If you find that the crime scene has footprints from a pair of Nike Air Jordans (with a distinctive tread design) and the suspect, in addition to being type O and blond, is also wearing Air Jordans with the same tread design, you are much closer to linking the suspect with the crime scene.

In this way, by accumulating bits of linking evidence in a chain, where each bit by itself isn't very strong but the set of all of them together is very strong, you can argue that your suspect really is the right person.

With DNA, the same kind of thinking is used; you can look for matches (based on sequence or on numbers of small repeating units of DNA sequence) at many different locations on the person's genome; one or two (even three) aren't enough to be confident that the suspect is the right one, but thirteen sites are used. A match at all thirteen is rare enough that you (or a prosecutor or a jury) can be very confident ("beyond a reasonable doubt") that the right person is accused.

See some recent articles about statistical analysis on this topic:

How is DNA typing done?

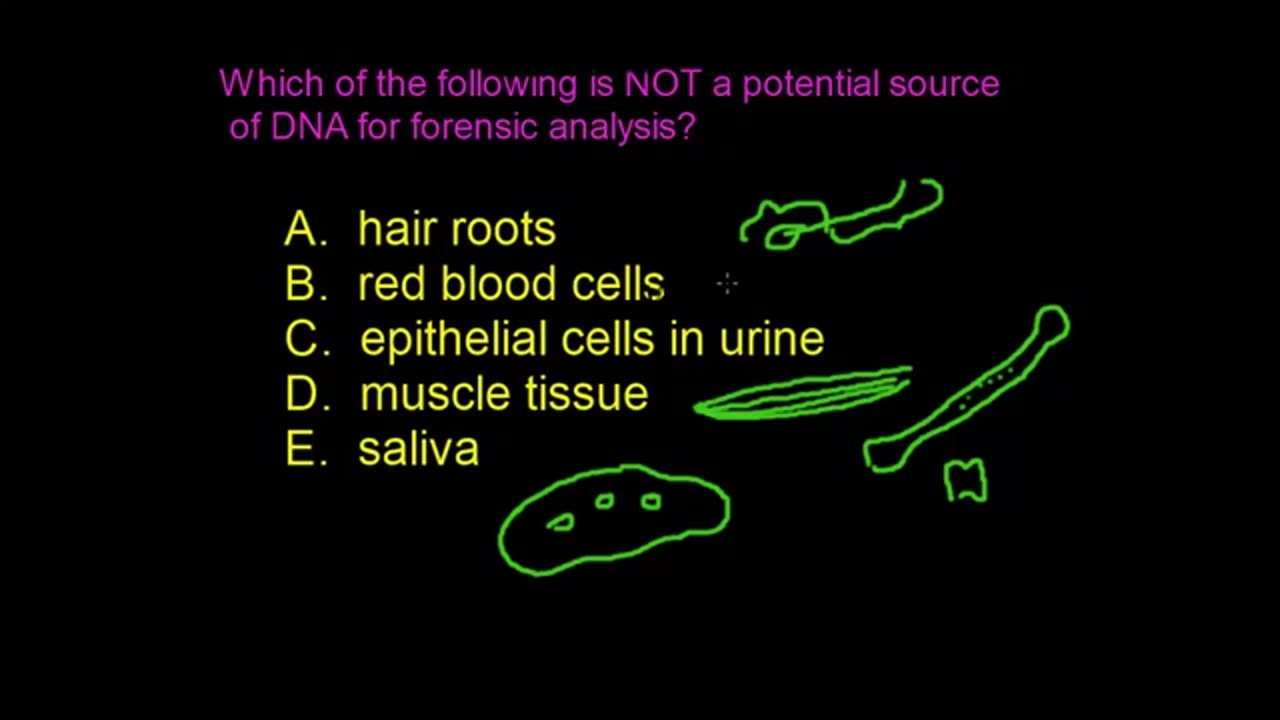

Only one-tenth of a single percent of DNA (about 3 million bases) differs from one person to the next. Scientists can use these variable regions to generate a DNA profile of an individual, using samples from blood, bone, hair, and other body tissues and products.

In criminal cases, this generally involves obtaining samples from crime-scene evidence and a suspect, extracting the DNA, and analyzing it for the presence of a set of specific DNA regions (markers).

-

14:17

14:17

RTT: Guns & Gear

17 hours ago $3.77 earnedBest Budget RMR Red Dot 2025? Gideon Optics Granite Review

25.1K4 -

2:05:05

2:05:05

BEK TV

1 day agoTrent Loos in the Morning - 12/05/2025

23.3K -

LIVE

LIVE

The Bubba Army

23 hours agoWill Michael Jordan TAKE DOWN NASCAR - Bubba the Love Sponge® Show | 12/05/25

1,055 watching -

35:55

35:55

ZeeeMedia

16 hours agoPfizer mRNA in Over 88% of Human Placentas, Sperm & Blood | Daily Pulse Ep 156

30.9K111 -

LIVE

LIVE

Pickleball Now

6 hours agoLive: IPBL 2025 Day 5 | Final Day of League Stage Set for Explosive Showdowns

136 watching -

9:03

9:03

MattMorseTV

19 hours ago $20.85 earnedIlhan Omar just got BAD NEWS.

52.4K107 -

2:02:41

2:02:41

Side Scrollers Podcast

23 hours agoMetroid Prime 4 ROASTED + Roblox BANNED for LGBT Propaganda + The “R-Word” + More | Side Scrollers

152K15 -

16:38

16:38

Nikko Ortiz

17 hours agoVeteran Tactically Acquires Everything…

34.4K2 -

20:19

20:19

MetatronHistory

2 days agoThe Mystery of Catacombs of Paris REVEALED

24.1K3 -

21:57

21:57

GritsGG

21 hours agoBO7 Warzone Patch Notes! My Thoughts! (Most Wins in 13,000+)

27.2K