Premium Only Content

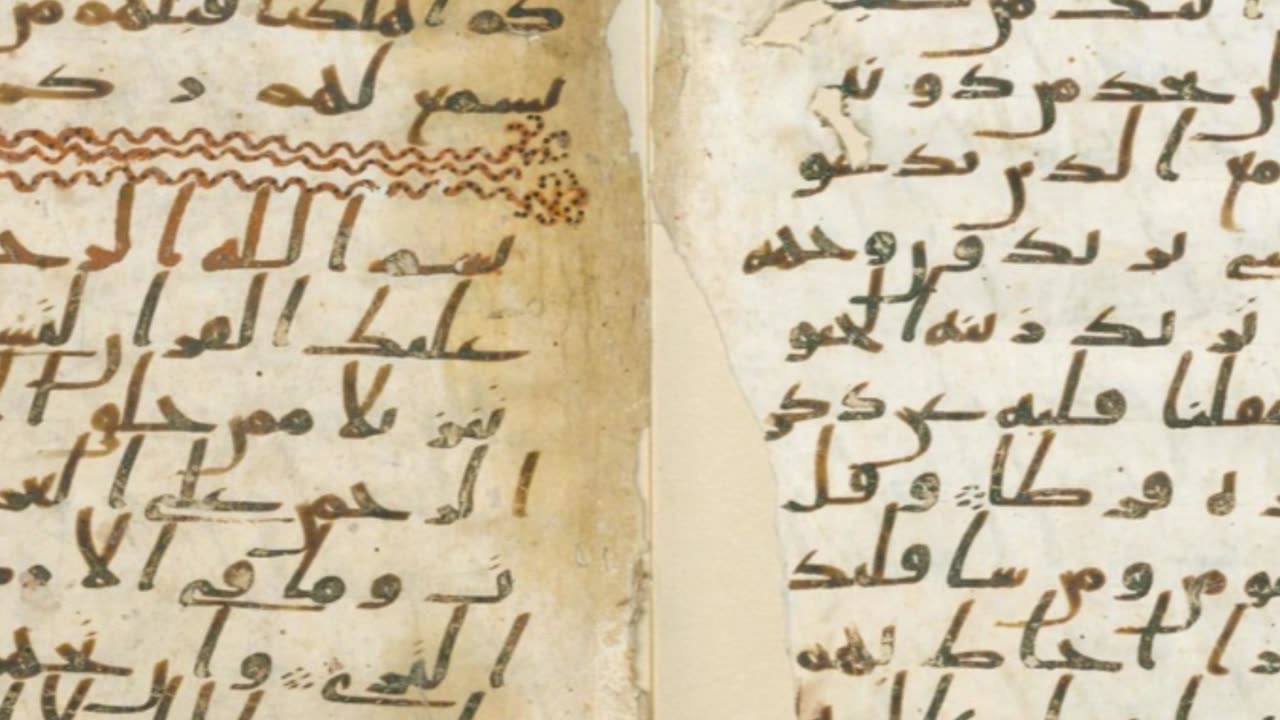

The Birmingham Quran Manuscript 03

The radiocarbon dating of the Birmingham Qur'an fragments, which include parts of Surahs 18 to 20, suggests with 95.4% accuracy that the parchment dates from 568-645 AD.

This is potentially 5 to over 80 years before the traditional Islamic account of the compilation of the Quran in 650 to 653 AD.

In Islamic tradition, the compilation of the Quran is attributed to the third caliph, Oothman. However, if the Birmingham Qur'an fragments are indeed part of the original Othmanic Codex, and date from 568-645 AD, it would suggest that the Quran was compiled and distributed earlier than previously thought.

This discrepancy raises questions about the accuracy of Islamic historiography.

The Birmingham fragments contain parts of the earlier so-called “Meccan Surahs” 18 to 20. From the end of surah 18 to the beginning of 20, in the order that is common today.

They follow Uthmanic logic with the non-chronological order of the surahs, which are lengthwise, except the first surah of the Koran, a polemic or curse upon Jews and Christians known as the al-Fatiha, which has 7 verses, and is of great importance, forming part of the main Islamic prayer.

The Birmingham Quran fragment is written in an early Arabic script known as Hijazi.

The concept of the Hijazi script, referring to the earliest known manuscripts of the Quran from the 7th-8th centuries, has been challenged by Estelle Whelan. She argues that defining a distinct "Hijazi script" based primarily on the form of the letter aleph and archaic explanations is a "scientific artefact" or artificial construction rather than an accurate representation of the early Quranic manuscripts.

Whelan contends that the traditional narrative of the Hijazi script being a distinct calligraphic style originating in the Heejaz region is oversimplified and lacks solid evidence. She suggests that the variations observed in early Quranic manuscripts may not necessarily represent a coherent regional script but rather reflect the natural diversity and evolution of Arabic writing during that period.

Her critique opposes the notion that the Hijazi script can be clearly defined and distinguished from other contemporaneous Arabic scripts based solely on paleographic features like the shape of the aleph. She argues that the explanations provided for the origins and characteristics of this script are rooted in traditional Islamic accounts, which may not align with a more critical examination of the manuscript evidence.

The fragments exhibit some shawādhdh in terms of variant spellings, verse numberings etc. that were likely acceptable variations before the Uthmanic standardisation.

The radiocarbon dating places it potentially before the traditional birth year of Mohammed.

There are differences in orthography and verse separations compared to the standard text. Early Quranic manuscripts often had variations before standardisation, despite false apologetics claims of a single, unaltered text, perfectly preserved exactly as sent down to Mohammed.

There have been multiple Quran standardisation efforts, a task which would be unnecessary if the Quran were 'perfectly preserved'.

-

LIVE

LIVE

megimu32

1 hour agoON THE SUBJECT: 1 Million Views Party! Diddy Drama, Marvel Weirdness, and Total Prom Chaos

139 watching -

1:18:44

1:18:44

Kim Iversen

5 hours agoMagnetic Pole Shift: Europe’s Blackout Is Just the Beginning | 90° Earth Flip Coming

73.2K197 -

2:44:58

2:44:58

Laura Loomer

4 hours agoEP118: LIVE COVERAGE: Trump Celebrates 100 Days In Office At Michigan Rally

47K22 -

3:40:42

3:40:42

Barry Cunningham

10 hours agoWATCH TRUMP RALLY LIVE: PRESIDENT TRUMP MARKS 100 DAYS IN OFFICE WITH A RALLY IN MICHIGAN

32.9K10 -

1:32:44

1:32:44

Badlands Media

10 hours agoBadlands Media Special Coverage: President Trump's 1st 100 Days Rally

40.2K2 -

LIVE

LIVE

RalliedLIVE

5 hours ago $0.57 earnedWarzone All Night w/ Ral

74 watching -

49:12

49:12

Sarah Westall

3 hours agoA Globalist Agenda or Chinese Payback? Fentanyl #1 Cause of Death for People Under 49

15.5K3 -

55:30

55:30

LFA TV

1 day ago| TRUMPET DAILY 4.29.25 7PM

15.2K1 -

7:27

7:27

China Uncensored

9 hours agoChina’s DISTURBING Expansion in Africa

18.2K13 -

1:24:27

1:24:27

Redacted News

5 hours agoELECTION SHOCK! Canada Declares War on U.S. and Trump, India going to war with Pakistan? | Redacted

138K253