Premium Only Content

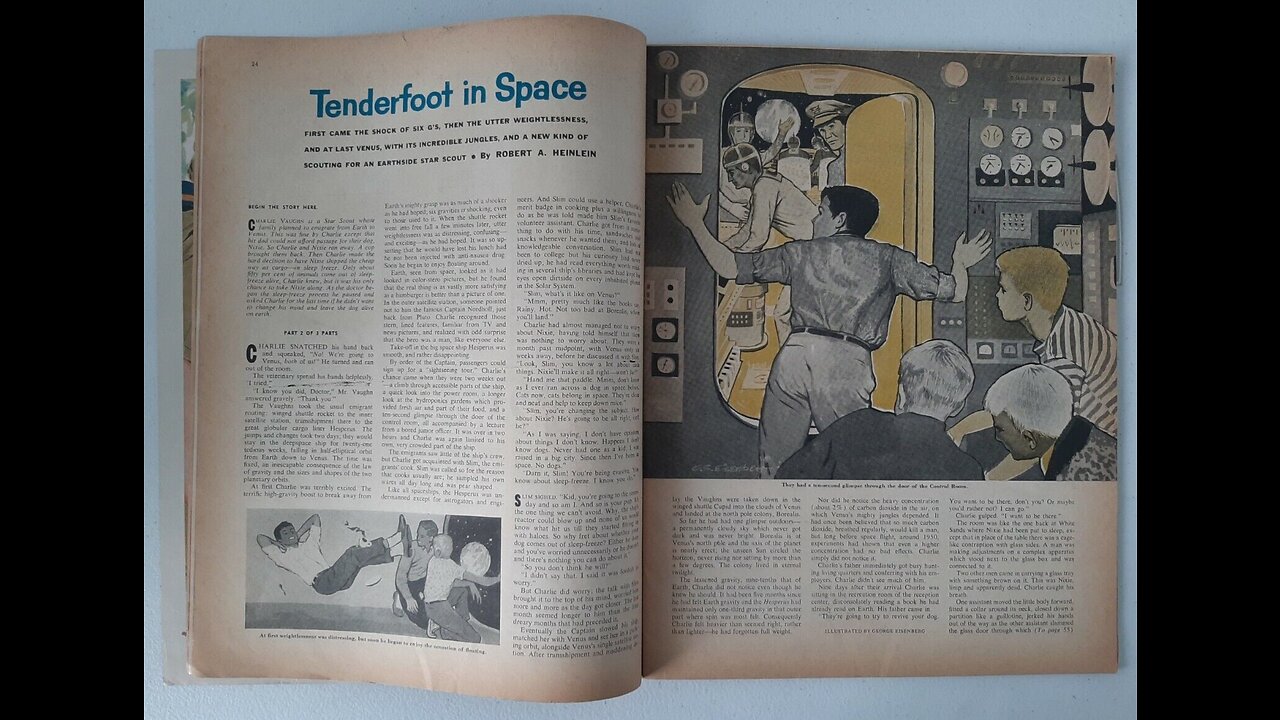

A TENDERFOOT IN SPACE. A Puke (TM) Audiobook

This e-text scanned, OCR'd and once overed by Gorgon776 on 16 May 2001. It needs some more correction. If you correct this text, update the version number by .1 and add your name here.

PukeOnaPlate 2023 Version plus point one.

Formatted for text to speech. Hyphens, brackets and ellipses replaced with commas. Mister and Doctor spelled out explicitly.

A TENDERFOOT IN SPACE.

When this book was in process, Doctor Kondo asked me whether there were any stories of Robert's which had not been reprinted. On looking over the list of stories, I found that "A Tenderfoot in Space" had never been printed in anything except when it originally appeared in Boys' Life. All copies in our possession had been sent to the UCSC Archives, so I asked them to Xerox those and send them to me. And found this introduction by Robert, which he had added to the carbon in the library before he sent it down there. I was completely surprised, and asked Doctor Kondo whether he would like to use it? Here it is.

Virginia Heinlein.

This was written a year before Sputnik and is laid on the Venus earthbound astronomers inferred before space probes. Two hours of rewriting, a word here, a word there, could change it to a planet around some other star. But to what purpose? Would The Tempest be improved if Bohemia had a sea coast? If I ever publish that collection of Boy Scout stories, this story will appear unchanged.

Nixie is, of course, my own dog. But in 1919, when I was 12 and a Scout, he had to leave me, a streetcar hit him.

If this universe has any reasonable teleology whatever, a point on which I am unsure, then there is some provision for the Nixies in it.

Part One.

"Heel, Nixie," the boy said softly, "and keep quiet."

The little mongrel took position left and rear of his boy, waited. He could feel that Charlie was upset and he wanted to know why, but an order from Charlie could not be questioned.

The boy tried to see whether or not the policeman was noticing them. He felt light-headed, neither he nor his dog had eaten that day. They had stopped in front of this supermarket, not to buy for the boy had no money left, but because of a "BOY WANTED" sign in the window.

It was then that he had noticed the reflection of the policeman in the glass.

The boy hesitated, trying to collect his cloudy thoughts. Should he go inside and ask for the job? Or should he saunter past the policeman? Pretend to be just out for a walk?

The boy decided to go on, get out of sight. He signaled the dog to stay close and turned away from the window. Nixie came along, tail high. He did not care where they went as long as he was with Charlie. Charlie had belonged to him as far back as he could remember; he could imagine no other condition. In fact Nixie would not have lived past his tenth day had not Charlie fallen in love with him; Nixie had been the least attractive of an unfortunate litter; his mother was Champion Lady Diana of Ojai, his father was unknown.

But Nixie was not aware that a neighbor boy had begged his life from his first owners. His philosophy was simple: enough to eat, enough sleep, and the rest of his time spent playing with Charlie. This present outing had been Charlie's idea, but any outing was welcome. The shortage of food was a nuisance but Nixie automatically forgave Charlie such errors, after all, boys will be boys and a wise dog accepted the fact. The only thing that troubled him was that Charlie did not have the happy heart which was a proper part of all hikes.

As they moved past the man in the blue uniform, Nixie felt the man's interest in them, sniffed his odor, but could find no real unfriendliness in it. But Charlie was nervous, alert, so Nixie kept his own attention high.

The man in uniform said, "Just a moment, son."

Charlie stopped, Nixie stopped. "You speaking to me, officer?"

"Yes. What's your dog's name?"

Nixie felt Charlie's sudden terror, got ready to attack. He had never yet had to bite anyone for his boy, but he was instantly ready. The hair between his shoulder blades stood up.

Charlie answered, "Uh, his name is “Spot.”

"So?" The stranger said sharply, "Nixie!"

Nixie had been keeping his eyes elsewhere, in order not to distract his ears, his nose, and the inner sense with which he touched people's feelings. But he was so startled at hearing this stranger call him by name that he turned his head and looked at him.

"His name is 'Spot,' is it?" the policeman said quietly. "And mine is Santa Claus. But you're Charlie Vaughn and you're going home." He spoke into his helmet phone: "Nelson, reporting a pickup on that Vaughn missing-persons flier. Send a car. I'm in front of the new supermarket."

Nixie had trouble sorting out Charlie's feelings; they were both sad and glad. The stranger's feelings were slightly happy but mostly nothing; Nixie decided to wait and see. He enjoyed the ride in the police car, as he always enjoyed rides, but Charlie did not, which spoiled it a little.

They were taken to the local Justice of the Peace. "You're Charles Vaughn?"

Nixie's boy felt unhappy and said nothing.

"Speak up, son," insisted the old man. "If you aren't, then you must have stolen that dog." He read from a paper "accompanied by a small brown mongrel, male, well trained, responds to the name 'Nixie.' Well?"

Nixie's boy answered faintly, "I'm Charlie Vaughn."

"That's better. You'll stay here until your parents pick you up." The judge frowned. "I can't understand your running away. Your folks are emigrating to Venus, aren't they?"

"Yes, sir."

"You're the first boy I ever met who didn't want to make the Big Jump." He pointed to a pin on the boy's lapel. "And I thought Scouts were trustworthy. Not to mention obedient. What got into you, son? Are you scared of the Big Jump? 'A Scout is Brave.' That doesn't mean you don't have to be scared, everybody is at times. 'Brave' simply means you don't run even if you are scared."

"I'm not scared," Charlie said stubbornly. "I want to go to Venus."

"Then why run away when your family is about to leave?"

Nixie felt such a burst of warm happy-sadness from Charlie that he licked his hand. "Because Nixie can't go!"

"Oh." The judge looked at boy and dog. "I'm sorry, son. That problem is beyond my jurisdiction." He drummed his desk top. "Charlie, will you promise, Scout's honor, not to run away again until your parents show up?"

"Uh, yes, sir."

"Okay. Joe, take them to my place. Tell my wife she had better see how recently they've had anything to eat."

The trip home was long. Nixie enjoyed it, even though Charlie's father was happy-angry and his mother was happy-sad and Charlie himself was happy-sad-worried. When Nixie was home he checked quickly through each room, making sure that all was in order and that there were no new smells. Then he returned to Charlie.

The feelings had changed. Mister Vaughn was angry, Missus Vaughn was sad, Charlie himself gave out such bitter stubbornness that Nixie went to him, jumped onto his lap, and tried to lick his face. Charlie settled Nixie beside him, started digging fingers into the loose skin back of Nixie's neck. Nixie quieted at once, satisfied that he and his boy could face together whatever it was, but it distressed him that the other two were not happy. Charlie belonged to him; they belonged to Charlie; things were better when they were happy, too.

Mister Vaughn said, "Go to bed, young man, and sleep on it. I'll speak with you again tomorrow."

"Yes, sir. Good night, sir."

"Kiss your mother goodnight. One thing more, Do I need to lock doors to be sure you will be here in the morning?"

"No, sir."

Nixie got on the foot of the bed as usual, tromped out a space, laid his tail over his nose, and started to go to sleep. But his boy was not sleeping; his sadness was taking the distressing form of heaves and sobs. So Nixie got up, went to the other end of the bed and licked away tears, then let himself be pulled into Charlie's arms and tears applied directly to his neck. It was not comfortable and too hot, besides being taboo. But it was worth enduring as Charlie started to quiet down, presently went to sleep.

Nixie waited, gave him a lick on the face to check his sleeping, then moved to his end of the bed.

Missus Vaughn said to Mister Vaughn, "Charles, isn't there anything we can do for the boy?"

"Confound it, Nora. We're getting to Venus with too little money as it is. If anything goes wrong, we'll be dependent on charity."

"But we do have a little spare cash."

"Too little. Do you think I haven't considered it? Why, the fare for that worthless dog would be almost as much as it is for Charlie himself! Out of the question! So why nag me? Do you think I enjoy this decision?"

"No, dear." Missus Vaughn pondered. "How much does Nixie weigh? I, well, I think I could reduce ten more pounds if I really tried."

"What? Do you want to arrive on Venus a living skeleton? You've reduced all the doctor advises, and so have I."

"Well, I thought that if somehow, among us, we could squeeze out Nixie's weight, it's not as if he were a Saint Bernard! We could swap it against what we weighed for our tickets."

Mister Vaughn shook his head unhappily. "They don't do it that way."

"You told me yourself that weight was everything. You even got rid of your chess set."

"We could afford thirty pounds of chess sets, or china, or cheese, where we can't afford thirty pounds of dog."

"I don't see why not."

"Let me explain. Surely, it's weight; it's always weight in a space ship. But it isn't just my hundred and sixty pounds, or your hundred and twenty, not Charlie's hundred and ten. We're not dead weight; we have to eat and drink and breathe air and have room to move, that last takes more weight because it takes more ship weight to hold a live person than it does for an equal weight in the cargo hold. For a human being there is a complicated formula, hull weight equal to twice the passenger's weight, plus the number of days in space times four pounds. It takes a hundred and forty-six days to get to Venus, so it means that the calculated weight for each of us amounts to six hundred and sixteen pounds before they even figure in our actual weights. But for a dog the rate is even higher, five pounds per day instead of four."

"That seems unfair. Surely a little dog can't eat as much as a man? Why, Nixie's food costs hardly anything."

Her husband snorted. "Nixie eats his own rations and half of what goes on Charlie's plate. However, it's not only the fact that a dog does eat more for his weight, but also they don't reprocess waste with a dog, not even for hydroponics."

"Why not? Oh, I know what you mean. But it seems silly."

"The passengers wouldn't like it. Never mind; the rule is: five pounds per day for dogs. Do you know what that makes Nixie's fare? Over three thousand dollars!"

"My goodness!"

"My ticket comes to thirty-eight hundred dollars and some, you get by for thirty-four hundred, and Charlie's fare is thirty-three hundred, yet that confounded mongrel dog, which we couldn't sell for his veterinary bills, would cost three thousand dollars. If we had that to spare, which we haven't, the humane thing would be to adopt some orphan, spend the money on him, and thereby give him a chance on an uncrowded planet, not waste it on a dog. Confound it! A year from now Charlie will have forgotten this dog."

"I wonder."

"He will. When I was a kid, I had to give up dogs, more than once they died, or something. I got over it. Charlie has to make up his mind whether to give Nixie away, or have him put to sleep." He chewed his lip. "We'll get him a pup on Venus."

"It won't be Nixie."

"He can name it Nixie. He'll love it as much."

"But, Charles, how is it there are dogs on Venus if it's so dreadfully expensive to get them there?"

"Eh? I think the first exploring parties used them to scout. In any case they're always shipping animals to Venus; our own ship is taking a load of milch cows."

"That must be terribly expensive."

"Yes and no, they ship them in sleep-freeze of course, and a lot of them never revive. But they cut their losses by butchering the dead ones and selling the meat at fancy prices to the colonists. Then the ones that live have calves and eventually it pays off." He stood up. "Nora, let's go to bed. It's sad, but our boy is going to have to make a man's decision. Give the mutt away, or have him put to sleep."

"Yes, dear." She sighed. "I'm coming."

Nixie was in his usual place at breakfast, lying beside Charlie's chair, accepting tidbits without calling attention to himself. He had learned long ago the rules of the dining room: no barking, no whining, no begging for food, no paws on laps, else the pets of his pet would make difficulties. Nixie was satisfied. He had learned as a puppy to take the world as it was, cheerful over its good points, patient with its minor shortcomings. Shoes were not to be chewed, people were not to be jumped on, most strangers must be allowed to approach the house, subject, of course, to strict scrutiny and constant alertness, a few simple rules and everyone was happy. Live and let live.

He was aware that his boy was not happy even this beautiful morning. But he had explored this feeling carefully, touching his boy's mind with gentle care by means of his canine sense for feelings, and had decided, from his superior maturity, that the mood would wear off. Boys were sometimes sad and a wise dog was resigned to it.

Mister Vaughn finished his coffee, put his napkin aside. "Well, young man?"

Charlie did not answer. Nixie felt the sadness in Charlie change suddenly to a feeling more aggressive and much stronger but no better. He pricked up his ears and waited.

"Chuck," his father said, "last night I gave you a choice. Have you made up your mind?"

"Yes, Dad." Charlie's voice was very low.

"Eh? Then tell me."

Charlie looked at the tablecloth. "You and Mother go to Venus. Nixie and I are staying here."

Nixie could feel anger welling up in the man, felt him control it. "You're figuring on running away again?"

"No, sir," Charlie answered stubbornly. "You can sign me over to the state school."

"Charlie!" It was Charlie's mother who spoke. Nixie tried to sort out the rush of emotions impinging on him.

"Yes," his father said at last, "I could use your passage money to pay the state for your first three years or so, and agree to pay your support until you are eighteen. But I shan’t."

"Huh? Why not, Dad?"

"Because, old-fashioned as it sounds, I am head of this family. I am responsible for it, and not just food, shelter, and clothing, but its total welfare. Until you are old enough to take care of yourself I mean to keep an eye on you. One of the prerogatives which go with my responsibility is deciding where the family shall live. I have a better job offered me on Venus than I could ever hope for here, so I'm going to Venus, and my family goes with me." He drummed on the table, hesitated. "I think your chances are better on a pioneer planet, too, but, when you are of age, if you think otherwise, I'll pay your fare back to Earth. But you go with us. Understand?"

Charlie nodded, his face glum.

"Very well. I'm amazed that you apparently care more for that dog than you do for your mother, and myself. But."

"It isn't that, Dad. Nixie needs."

"Quiet. I don't suppose you realize it, but I tried to figure this out, I'm not taking your dog away from you out of meanness. If I could afford it, I'd buy the hound a ticket. But something your mother said last night brought up a third possibility."

Charlie looked up suddenly, and so did Nixie; wondering why the surge of hope in his boy.

"I can't buy Nixie a ticket, but it's possible to ship him as freight."

"Huh? Why, sure, Dad! Oh, I know he'd have to be caged up, but I'd go down and feed him every day and pet him and tell him it was all right and."

"Slow down! I don't mean that. All I can afford is to have him shipped the way animals are always shipped in space ships, in sleep-freeze."

Charlie's mouth hung open. He managed to say, "But that's."

"That's dangerous. As near as I remember, it's about fifty-fifty whether he wakes up at the other end. But if you want to risk it, well, perhaps it's better than giving him away to strangers, and I'm sure you would prefer it to taking him down to the vet's and having him put to sleep."

Charlie did not answer. Nixie felt such a storm of conflicting emotions in Charlie that the dog violated dining room rules; he raised up and licked the boy's hand.

Charlie grabbed the dog's ear. "All right, Dad," he said gruffly. "We'll risk it, if that's the only way Nixie and I can still be partners."

Nixie did not enjoy the last few days before leaving; they held too many changes. Any proper dog likes excitement, but home is for peace and quiet. Things should be orderly there, food and water always in the same place, newspapers to fetch at certain hours, milkmen to supervise at regular times, furniture all in its proper place. But during that week all was change, nothing on time, nothing in order. Strange men came into the house (always a matter for suspicion), and he, Nixie, was not even allowed to protest, much less give them the what-for they had coming.

He was assured by Charlie and Missus Vaughn that it was "all right" and he had to accept it, even though it obviously was not all right. His knowledge of English was accurate for a few dozen words but there was no way to explain to him that almost everything owned by the Vaughn family was being sold, or thrown away, nor would it have reassured him. Some things in life were permanent; he had never doubted that the Vaughn home was first among these certainties. By the night before they left, the rooms were bare except for beds. Nixie trotted around the house, sniffing places where familiar objects had been, asking his nose to tell him that his eyes deceived him, whining at the results. Even more upsetting than physical change was emotional change, a heady and not entirely happy excitement which he could feel in all three of his people.

There was a better time that evening, as Nixie was allowed to go to Scout meeting. Nixie always went on hikes and had formerly attended all meetings. But he now attended only outdoor meetings since an incident the previous winter, Nixie felt that too much fuss had been made about it, just some spilled cocoa and a few broken cups and anyhow it had been that cat's fault.

But this meeting he was allowed to attend because it was Charlie's last Scout meeting on Earth. Nixie was not aware of that but he greatly enjoyed the privilege, especially as the meeting was followed by a party at which Nixie became comfortably stuffed with hot dogs and pop. Scoutmaster McIntosh presented Charlie with a letter of withdrawal, certifying his status and merit badges and asking his admission into any troop on Venus. Nixie joined happily in the applause, trying to out bark the clapping.

Then the Scoutmaster said, “Okay, Rip."

Rip was senior patrol leader. He got up and said, "Quiet, fellows. Hold it, you crazy savages! Charlie, I don't have to tell you that we're all sorry to see you go, but we hope you have a swell time on Venus and now and then send a postcard to Troop Twenty-Eight and tell us about it, we'll post 'em on the bulletin board. Anyhow, we wanted to get you a going-away present. But Mister McIntosh pointed out that you were on a very strict weight allowance and practically anything would either cost you more to take with you than we had paid for it, or maybe you couldn't take it at all, which wouldn't be much of a present.

"But it finally occurred to us that we could do one thing. Nixie."

Nixie's ears pricked. Charlie said softly, "Steady, boy."

"Nixie has been with us almost as long as you have. He's been around, poking his cold nose into things, longer than any of the tenderfeet, and longer even than some of the second class. So we decided he ought to have his own letter of withdrawal, so that the troop you join on Venus will know that Nixie is a Scout in good standing. Give it to him, Kenny."

The scribe passed over the letter. It was phrased like Charlie's letter, save that it named "Nixie Vaughn, Tenderfoot Scout" and diplomatically omitted the subject of merit badges. It was signed by the scribe, the scoutmaster, and the patrol leaders and countersigned by every member of the troop. Charlie showed it to Nixie, who sniffed it. Everybody applauded, so Nixie joined happily in applauding himself.

"One more thing," added Rip. "Now that Nixie is officially a Scout, he has to have his badge. So send him front and center."

Charlie did so. They had worked their way through the Dog Care merit badge together while Nixie was a pup, all feet and floppy ears; it had made Nixie a much more acceptable member of the Vaughn family. But the rudimentary dog training required for the merit badge had stirred Charlie's interest; they had gone on to Dog Obedience School together and Nixie had progressed from easy spoken commands to more difficult silent hand signals.

Charlie used them now. At his signal Nixie trotted forward, sat stiffly at attention, front paws neatly drooped in front of his chest, while Rip fastened the tenderfoot badge to his collar, then Nixie raised his right paw in salute and gave one short bark, all to hand signals.

The applause was loud and Nixie trembled with eagerness to join it. But Charlie signaled "hold and quiet," so Nixie remained silently poised in salute until the clapping died away. He returned to heel just as silently, though quivering with excitement. The purpose of the ceremony may not have been clear to him, if so, he was not the first tenderfoot Scout to be a little confused. But it was perfectly clear that he was the center of attention and was being approved of by his friends; it was a high point in his life.

But all in all there had been too much excitement for a dog in one week; the trip to White Sands, shut up in a travel case and away from Charlie, was the last straw. When Charlie came to claim him at the baggage room of White Sands Airport, his relief was so great that he had a puppyish accident, and was bitterly ashamed.

He quieted down on the drive from airport to spaceport, then was disquieted again when he was taken into a room which reminded him of his unpleasant trips to the veterinary, the smells, the white-coated figure, the bare table where a dog had to hold still and be hurt. He stopped dead.

"Come, Nixie!" Charlie said firmly. "None of that, boy. Up!"

Nixie gave a little sigh, advanced and jumped onto the examination table, stood docile but trembling.

"Have him lie down," the man in the white smock said. "I've got to get the needle into the large vein in his foreleg."

Nixie did so on Charlie's command, then lay tremblingly quiet while his left foreleg was shaved in a patch and sterilized. Charlie put a hand on Nixie's shoulder blades and soothed him while the veterinary surgeon probed for the vein. Nixie bared his teeth once but did not growl, even though the fear in the boy's mind was beating on him, making him just as afraid.

Suddenly the drug reached his brain and he slumped limp.

Charlie's fear surged to a peak but Nixie did not feel it. Nixie's tough little spirit had gone somewhere else, out of touch with his friend, out of space and time, wherever it is that the "I" within a man or a dog goes when the body wrapping it is unconscious.

Charlie said shrilly, "Is he all right?"

"Eh? Of course."

"Uh, I thought he had died."

"Want to listen to his heart beat?"

"Uh, no, if you say he's all right. Then he's going to be okay? He'll live through it?"

The doctor glanced at Charlie's father, back at the boy, let his eyes rest on Charlie's lapel. "Star Scout, eh?"

"Uh, yes, sir."

"Going on to Eagle?"

"Well, I'm going to try, sir."

"Good. Look, son. If I put your dog over on that shelf, in a couple of hours he'll be sleeping normally and by tomorrow he won't even know he was out. But if I take him back to the chill room and start him on the cycle, "He shrugged. "Well, I've put eighty head of cattle under today. If forty percent are revived, it's a good shipment. I do my best."

Charlie looked grey. The surgeon looked at Mister Vaughn, back at the boy. "Son, I know a man who's looking for a dog for his kids. Say the word and you won't have to worry about whether this pooch's system will recover from a shock it was never intended to take."

Mister Vaughn said, "Well, son?"

Charlie stood mute, in an agony of indecision. At last Mister Vaughn said-sharply, "Chuck, we've got just twenty minutes before we must check in with Emigration. Well? What's your answer?"

Charlie did not seem to hear. Timidly. He put out one hand, barely touched the still form with the staring, unseeing eyes. Then he snatched his hand back and squeaked, "No! We're going to Venus, both of us!", turned and ran out of the room.

The veterinary spread his hands helplessly. "I tried."

"I know you, did, Doctor," Mister Vaughn answered gravely. "Thank you."

The Vaughn’s took the usual emigrant routing: winged shuttle rocket to the inner satellite station, ugly wingless ferry rocket to the outer station, transshipment there to the great globular cargo liner Hesperus. The jumps and changes took two days; they stayed in the deep space ship for twenty-one tedious weeks, falling in half-elliptical orbit from Earth down to Venus.

The time was fixed, an inescapable consequence of the law of gravity and the sizes and shapes of the two planetary orbits.

At first Charlie was terribly excited. The terrific high gravity boost to break away from Earth's mighty grasp was as much of a shocker as he had hoped; six gravities is shocking, even to those used to it. When the shuttle rocket went into free fall a few minutes later, utter weightlessness was as distressing, confusing, and exciting, as he had hoped. It was so upsetting that he would have lost his lunch had he not been injected with anti-nausea drug.

Earth, seen from space, looked as it had looked in color-stereo pictures, but he found that the real thing is as vastly more satisfying as a hamburger is better than a picture of one. In the outer satellite station, someone pointed out to him the famous Captain Nordhoff, just back from Pluto. Charlie recognized those stern, lined features, familiar from TV and news pictures, and realized with odd surprise that the hero was a man, like everyone else. He decided to be a spaceman and famous explorer himself.

S. S. Hesperus was a disappointment. It "blasted" away from the outer station with a gentle shove, one tenth gravity, instead of the soul-satisfying, bone grinding, ear-shattering blast with which the shuttle had left Earth. Also, despite its enormous size, it was terribly crowded. After the Captain had his ship in orbit to intercept Venus five months later, he placed spin on his ship to give his passengers artificial weight, which took from Charlie the pleasant new feeling of weightlessness which he had come to enjoy.

He was bored silly in five days, and there were five months of it ahead. He shared a cramped room with his father and mother and slept in a hammock swung "nightly", the ship used Greenwich time, between their bunks. Hammock in place, there was no room in the cubicle; even with it stowed, only one person could dress at a time. The only recreation space was the mess rooms and they were always crowded. There was one view port in his part of the ship. At first it was popular, but after a few days even the kids didn't bother, for the view was always the same: stars, and more stars.

By order of the Captain, passengers could sign up Tor a "sightseeing tour." Charlie's chance came when they were two weeks out, a climb through accessible parts of the ship, a quick look into the power room, a longer look at the hydroponics gardens which provided fresh air and part of their food, and a ten-second glimpse through the door of the Holy of Holies, the control room, all accompanied by a lecture from a bored junior officer. It was over in two hours and Charlie was again limited to his own, very crowded part of the ship.

Up forward there were privileged passengers, who had staterooms as roomy as those of the officers and who enjoyed the luxury of the officers' lounge. Charlie did not find out that they were aboard for almost a month, but when he did, he was righteously indignant.

His father set him straight. "They paid for it."

"Huh? But we paid, too. Why should they get."

"They paid for luxury. Those first-class passengers each paid~ about three times what your ticket cost, or mine. We got the emigrant rate, transportation and food and a place to sleep.”

"I don't think it's fair."

Mister Vaughn shrugged. "Why should we have something we haven't paid for."

"Uh, well, Dad, why should they be able to pay for luxuries we can't afford?"

"A good question. Philosophers ever since Aristotle have struggled with that one. Maybe you'll tell me, someday."

"Huh? What do you mean, Dad?"

"Don't say 'Huh.' Chuck, I'm taking you to a brand new planet. If you try, you can probably get rich. Then maybe you can tell me why a man with money can command luxuries that poor people can't."

"But we aren't poor!"

"No, we are not. But we aren't rich either. Maybe you've got the drive to get rich. One thing is sure: on Venus the opportunities are all around you. Never mind, how about a game before dinner?"

Charlie still resented being shut out of the nicest parts of the ship, he had never felt like a second-class anything, citizen, or passenger, before in his life; the feeling was not pleasant.

He decided to get rich on Venus. He would make the biggest uranium strike in history; then he would ride first class between Venus and Earth whenever he felt like it, that would teach those stuck-up snobs!

He then remembered he had already decided to be a famous spaceman. Well, he would do both. Someday he would own a space line, and one of the ships would be his private yacht. But by the time the Hesperus reached the halfway point he no longer thought about it.

The emigrants saw little of the ship's crew, but Charlie got acquainted with Slim, the emigrants' cook. Slim was called so for the reason that cooks usually are; he sampled his own wares all day long and was pear shaped.

Like all space ships, the Hesperus was undermanned except for astrogators and engineers, why hire a cook's helper when the space can be sold to a passenger? It was cheaper to pay high wages to a cook who could perform production-line miracles without a helper. And Slim could.

But he could use a helper. Charlie's merit badge in cooking plus a willingness to do as he was told made him Slim's favorite volunteer assistant. Charlie got from it something to do with his time, sandwiches and snacks whenever he wanted them, and lots of knowledgeable conversation. Slim had not been to college but his curiosity had never dried up; he had read everything worth reading in several ship's libraries and had kept his eyes open dirtside on every inhabited planet in the Solar System.

"Slim, what's it like on Venus?"

"Mum, pretty much like the books say. Rainy. Hot. Not too bad at Borealis, where you'll land."

"Yes, but what's it like?"

"Why not wait and see? Give that stew a stir, and switch on the short-waver. Did you know that they used to figure that Venus couldn't be lived on?"

"Huh? No, I didn't."

"Struth. Back in the days when we didn't have space flight, scientists were certain that Venus didn't have either oxygen nor water. They figured it was a desert, with sand storms and no air you could breathe. Proved it, all by scientific logic."

"But how could they make such a mistake? I mean, obviously, with clouds all over it and."

"The clouds didn't show water vapor, not through a spectroscope they didn't. Showed lots of carbon dioxide, though, and by the science of the last century they figured they had proved that Venus couldn't support life."

"Funny sort of science! I guess they were pretty ignorant in those days."

"Don't go running down our grandfathers. If it weren't for them, you and I would be squatting in a cave, scratching fleas. No, Bub, they were pretty sharp; they just didn't have all the facts. We've got more facts, but that doesn't make us smarter. Put them biscuits over here. The way I see it, it just goes to show that the only way to tell what's in a stew is to eat it, and even then you aren't always sure. Venus turned out to be a very nice place. For ducks. If there were any ducks there. Which there ain't."

"Do you like Venus?"

"I like any place I don't have to stay in too long. Okay, let's feed the hungry mob."

The food in the Hesperus was as good as the living accommodations were bad. This was partly Slim's genius, but was also the fact that food in a space ship costs by its weight; what it had cost Earthside matters little compared with the expense of lifting it off Earth. The choicest steaks cost the spaceline owners little more than the same weight of rice, and any steaks left over could be sold at high prices to colonist’s weary for a taste of Earth food. So the emigrants ate as well as the first class passengers, even though not with fine service and fancy surroundings. When Slim was ready he opened a shutter in the galley partition and Charlie dealt out the wonderful viands like chow in a Scout camp to passengers queued up with plates. Charlie enjoyed this chore. It made him feel like a member of the crew, a spaceman himself.

Charlie almost managed not to worry about Nixie, having told himself that there was nothing to worry about. They were a month past midpoint, with Venus only six weeks away before he discussed it with Slim. "Look, Slim, you know a lot about such things. Nixie'll make it all right, won't he?"

"Hand me that paddle; Mum, don't know as I ever ran across a dog in space before. Cats now, cats belong in space. They're clean and neat and help to keep down mice and rats."

"I don't like cats."

"Ever lived with a cat? No, I see you haven't. How can you have the gall not to like something you don't know anything about? Wait till you've lived with a cat, then tell me what you think.

Until then, well, who told you were entitled to an opinion?"

"Huh? Why, everybody is entitled to his own opinion!"

"Nonsense, Bub. Nobody is entitled to an opinion about something he is ignorant of. If the Captain told me how to bake a cake, I would politely suggest that he not stick his nose into my trade, contrariwise, I never tell him how to plot an orbit to Mars."

"Slim, you're changing the subject. How about Nixie? He's going to be all right, isn't he?"

"As I was saying, I don't have opinions about things I don't know. Happens I don't know dogs. Never had one as a kid; I was raised in a big city. Since then I've been in space. No dogs."

"Darn it, Slim!, you're being evasive: You know about sleep-freeze. I know you do."

Slim sighed. "Kid, you're going to die someday and so am I. And so is your pup. It's the one thing we can't avoid. Why, the ship's reactor could blow up and none of us would know what hit us till they started fitting us with haloes. So why fret about whether your dog comes out of sleep-freeze? Either he does and you've worried unnecessarily, or he doesn't and there's nothing you can do about it."

"So you don't think he will?"

"I didn't say that. I said it was foolish to worry."

But Charlie did worry; the talk with Slim brought it to the top of his mind, worried him more and more as the day got closer. The last month seemed longer to him than the four dreary months that had preceded it.

As for Nixie, time meant nothing to him. Suspended between life and death, he was not truly in the Hesperus at all; but somewhere else, outside of time. It was merely his shaggy little carcass that lay, stored like a ham, in the frozen hold of the ship.

Eventually the Captain slowed his ship, matched her with Venus and set her in a, parking orbit alongside Venus's single satellite station. After transshipment and maddening delay the Vaughns were taken down in the winged shuttle Cupid into the clouds of Venus and landed at the north pole colony, Borealis.

For Charlie there was a still more maddening delay: cargo, which included Nixie, was unloaded after passengers and took many days because the mighty Hesperus held so much more than the little Cupid. He could not even go over to the freight sheds to inquire about Nixie as immigrants were held at the reception center for quarantine. Each one had received many shots during the five-month trip to inoculate them against the hazards of Venus; now they found that they must wait not only on most careful physical examination and observation to make sure that they were not bringing Earth diseases in with them but also to receive more shots not available aboard ship. Charlie spent the days with sore arms and gnawing anxiety.

So far he had had one glimpse outdoors, a permanently cloudy sky which never got dark and was never very bright. Borealis is at Venus's north pole and the axis of the planet is nearly erect; the unseen Sun circled the horizon, never rising nor setting by more than a few degrees. The colony lived in eternal twilight.

The lessened gravity, nine-tenths that of Earth, Charlie did not notice even though he knew he should. It had been five months since he had felt Earth gravity and the Hesperus had maintained only one-third gravity in that outer part, where spin was most felt. Consequently Charlie felt heavier than seemed right, rather than lighter, his feet had forgotten full weight.

Nor did he notice the heavy concentration, about 2 percent, of carbon dioxide in the air, on which Venus's mighty jungles depended. It had once been believed that so much carbon dioxide,

breathed regularly, would kill a man, but long before space flight, around 1950, experiments had shown that even a higher concentration had no bad effects. Charlie simply didn't notice it.

All in all, he might have been waiting in a dreary, barracks-like building in some tropical port on Earth. He did not see much of his father, who was busy by telephone and by germproof conference cage, conferring with his new employers and arranging for quarters, nor did he see much of his mother; Missus Vaughn had found the long trip difficult and was spending most of her time lying down.

Nine days after their arrival Charlie was sitting in the recreation room of the reception center, disconsolately reading a book he had already read on Earth. His father came in. "Come along."

"Huh? What's up?"

"They're going to try to revive your dog. You want to be there, don't you? Or maybe you'd rather not? I can go, and come back and tell you what happened."

Charlie gulped. "I want to be there. Let's go."

The room was like the one back at White Sands where Nixie had been put to sleep, except that in place of the table there was a cage-like contraption with glass sides. A man was making adjustments on a complex apparatus which stood next to the glass box and was connected to it. He looked up. "Yes? We're busy."

"My name is Vaughn and this is my son Charlie. He's the owner of the dog."

The man frowned. "Didn't you get my message? I'm Doctor Zecker, by the way. You're too soon; we're just bringing the dog up to temperature."

Mister Vaughn said, "Wait here, Charlie," crossed the room and spoke in a low voice to Zecker.

Zecker shook his head. "Better wait outside."

Mister Vaughn again spoke quietly; Doctor Zecker answered, "You don't understand. I don't even have proper equipment, I've had to adapt the force breather we use for hospital monkeys. It was never meant for a dog."

They argued in whispers for a few moments. They were interrupted by an amplified voice from outside the room "Ready with ninety-seven-X, Doctor, that's the dog."

Zecker called back, "Bring it in!", then went on to Mister Vaughn, "All right, keep him out of the way. Though I still say he would be better off outside." He turned, paid them no further attention.

Two men, came in, carrying a large tray. Something quiet and not very large was heaped on it, covered by dull blue cloth. Charlie whispered, "Is that Nixie?"

"I think so," his father-answered in a low voice. "Keep quiet and watch."

"Can't I see him?"

"Stay where you are and don't say a word, else the doctor will make you leave."

Once inside, the team moved quickly and without speaking, as if this were something rehearsed again and again, something that must be done with great speed and perfect precision. One of them opened the glass box; the other placed the tray inside, uncovered its burden. It was Nixie, limp and apparently dead. Charlie caught his breath.

One assistant moved the little body forward, fitted a collar around its neck, closed down a partition like a guillotine, jerked his hands out of the way as the other assistant slammed the glass door through which they had put the dog in, quickly sealed it. Now Nixie was shut tight in a glass coffin, his head lying outside the end partition, his body inside. "Cycle!"

Even as he said it, the first assistant slapped a switch and fixed his eyes on the instrument board and Doctor Zecker thrust both arms into long rubber gloves passing through the glass, which allowed his hands to be inside with Nixie's body. With rapid, sure motions he picked up a hypodermic needle, already waiting inside, shoved it deep into the dog's side.

"Force breathing established."'

"No heart action, Doctor!"

The reports came one on top of the other, Zecker looked up at the dials, looked back at the dog and cursed. He grabbed another needle. This one he entered gently, depressed the plunger most carefully, with his eyes on the dials. "Fibrillation."

"I can see!" he answered snappishly, put down the hypo and began to massage the dog in time with the ebb and surge of the "iron lung."

And Nixie lifted his head and cried.

It was more than an hour before Doctor Zecker let Charlie take the dog away. During most of this time the cage was open and Nixie was breathing on his own, but with the apparatus still in place, ready to start again if his heart or lungs should falter in their newly relearned trick of keeping him alive. But during this waiting time Charlie was allowed to stand beside him, touch him, sooth and pet him to keep him quiet.

At last the doctor picked up Nixie and put him in Charlie's arms. "Okay, take him. But keep him quiet; I don't want him running around for the next ten hours. But not too quiet, don't let him sleep."

"Why not, Doctor?" asked Mister Vaughn.

"Because sometimes, when you think they've made it, they just lie down and quit, as if they had had a taste of death and found they liked it. This pooch has had a' near squeak, we have only seven minutes to restore blood supply to the brain. Any longer than that, well, the brain is permanently damaged and you might as well put it out of its misery."

"You think you made it in time?"

"Do you think," Zecker answered angrily, "that I would let you take the dog if I hadn't?"

"Sorry."

"Just keep him quiet, but not too quiet. Keep him awake."

Charlie answered solemnly, "I will, Doctor Nixie's going to be all right, I know he is."

Charlie stayed awake all night long, talking to Nixie, petting him, keeping him quiet but not asleep. Neither one of his parents tried to get him to go to bed.

Part Two.

Nixie liked Venus. It was filled with a thousand new smells, all worth investigating, countless new sounds, each of which had to be catalogued. As official guardian of the Vaughn family and of Charlie in particular, it was his duty and pleasure to examine each new phenomenon, decide whether or not it was safe for his people; he set about it happily.

It is doubtful that he realized that he had traveled other than that first lap in the traveling case to White Sands. He took up his new routine without noticing the five months clipped out of his life; he took charge of the apartment assigned to the Vaughn family, inspected it thoroughly, then nightly checked it to be sure that all was in order and safe before he tromped out his place on the foot of Charlie's bed and tucked his tail over his nose.

He was aware that this was a new place, but he was not homesick. The other home had been satisfactory and he had never dreamed of leaving it, but this new home was still better.

Not only did it have Charlie, without whom no place could be home, not only did it have wonderful odors, but also he found the people more agreeable. In the past, many humans had been quite stuffy about flower beds and such trivia, but here he was almost never scolded or chased away; on the contrary people were anxious to speak to him, pet him, feed him. His popularity was based on arithmetic: Borealis had fifty-five thousand people but only eleven dogs; many colonists were homesick for man's traditional best friend. Nixie did not know this, but he had great capacity for enjoying the good things in life without worrying about why.

Mister Vaughn found Venus satisfactory. His work for Synthetics of Venus, Limited, was the sort of work he had done on Earth, save that he was now paid more and given more responsibility.

The living quarters provided by the company were as comfortable as the house he had left back on Earth and he was unworried about the future of his family for the first time in years.

Missus Vaughn found Venus bearable but she was homesick much of the time.

Charlie, once he was over first the worry and then the delight of waking Nixie, found Venus interesting, less strange than he had expected, and from time to time he was homesick. But before long he was no longer homesick; Venus was home. He knew now what he wanted to be: a pioneer. When he was grown he would head south, deep into the unmapped jungle, carve out a plantation.

The jungle was the greatest single fact about Venus. The colony lived on the bountiful produce of the jungle. The land on which Borealis sat, buildings and spaceport, had been torn away from the hungry jungle only by flaming it dead, stabilizing the muck with gel-forming chemicals, and poisoning the land thus claimed, then flaming, cutting, or poisoning any hardy survivor that pushed its green nose up through the captured soil.

The Vaughn family lived in a large apartment building which sat on land newly captured. Facing their front door, a mere hundred feet away across scorched and poisoned soil, a great shaggy dark-green wall loomed higher than the buffer space between. But the mindless jungle never gave up. The vines, attracted by light, their lives were spent competing for light energy, felt their way into the open space, tried to fill it. They grew with incredible speed. One day after breakfast Mister Vaughn tried to go out his own front door, found his way hampered. While they had slept a vine had grown across the hundred-foot belt, supporting itself by tendrils against the dead soil, and had started up the front of the building.

The police patrol of the city were armed with flame guns and spent most of their time cutting back such hardy intruders. While they had power to enforce the law, they rarely made an arrest. Borealis was a city almost free of crime; the humans were too busy fighting nature in the raw to require much attention from policemen.

But the jungle was friend as well as enemy. Its lusty life offered food for millions and billions of humans in place of the few thousands already on Venus. Under the jungle lay beds of peat, still farther down were thick coal seams representing millions of years of lush jungle growth, and pools of oil waiting to be tapped. Aerial survey by jet-copter in the volcanic regions promised uranium and thorium when man could cut his way through and get at it. The planet offered unlimited wealth. But it did not offer it to sissies.

Charlie quickly bumped his nose into one respect in which Venus was not for sissies. His father placed him in school, he was assigned to a grade taught by Mister deSoto. The school room was not attractive, "grim" was the word Charlie used, but he was not surprised, as most buildings in Borealis were unattractive, being constructed either of spongy logs or of lignin panels made from jungle growth.

But the school itself was "grim." Charlie had been humiliated by being placed one grade lower than he had expected; now he found that the lessons were stiff and that Mister deSoto did not have the talent, or perhaps the wish to make them fun. Resentfully, Charlie loafed.

After three weeks Mister deSoto kept him in after school. "Charlie, what's wrong?"

"Huh? I mean, 'Sir?"

"You know what I mean. You've been in my class nearly a month. You haven't learned anything. Don't you want to?"

"What? Why, sure I do."

"Surely' in that usage, not 'sure.' Very well, so you want to learn; why haven't you?"

Charlie stood silent. He wanted to tell Mister deSoto what a swell place Horace Mann Junior High School had been, with its teams and its band and its student plays and its student council, this crazy school didn't even have a student council! And its study projects picked by the kids themselves, and the Spring Outburst and Sneak Day, and, oh, shucks!

But Mister deSoto was speaking. "Where did you last go to school, Charlie?"

Charlie stared. Didn't the teacher even bother to read his transcript? But he told him and added, "I was a year farther along there. I guess I'm bored, having to repeat."

"I think you are, too, but I don't agree that you are repeating. They had an eighteen-year Jaw there, didn't they?"

"Sir?"

"You were required to attend school until you were eighteen Earth-years old?"

"Oh, that! Sure. I mean 'surely.' Everybody goes to school until he's eighteen. That's to 'discourage juvenile delinquency," he quoted.

"I wonder. Nobody ever flunked, I suppose."

"Sir?"

"Failed. Nobody ever got tossed out of school or left back for failing his studies?"

"Of course not, Mister deSoto. You have to keep age groups together, or they don't develop socially as they should."

"Who told you that?"

"Why, everybody knows that. I've been hearing that ever since I was in kindergarten. That's what education is for, social development."

Mister deSoto leaned back, rubbed his nose. Presently he said slowly; "Charlie, this isn't that kind of a school at all."

Charlie waited. He was annoyed at not being invited to sit down and was wondering what would happen if he sat down anyway.

"In the first place we don't have the eighteen-year rule. You can quit school today. You know how to read. Your handwriting is sloppy but it will do. You are quick in arithmetic. You can't spell worth a hoot, but that's your misfortune; the city fathers don't care whether you learn to spell or not. You've got all the education the City of Borealis feels obliged to give you. If you want to take a flame gun and start carving out your chunk of the jungle, nobody is standing in your way. I can write a note to the Board of Education, telling them that Charles Vaughn, Junior has gone as far as he ever will. You needn't come back tomorrow."

Charlie gulped. He had never heard of anyone being dropped from school for anything less than a knife fight. It was unthinkable, what would his folks say?

"On the other hand," Mister deSoto went on, "Venus needs educated citizens. We'll keep anybody as long as they keep learning. The city will even send you back to Earth for advanced training if you are worth it, because we need scientists and engineers, and more teachers. But this is a struggling new community and it doesn't have a penny to waste on kids who won't study. We do flunk them in this school. If you don't study, we'll lop you off so fast you'll think you've been trimmed with a flame gun. We're not running the sort of overgrown kindergarten you were in. It's up to you. Buckle down and learn, or get out. So go home and talk it over with your folks."

Charlie was stunned. "Uh, Mister deSoto? Are you going to talk to my father?"

"What? Heavens, no! You are their responsibility, not mine. I don't care what you do. That's all. Go home."

Charlie went home, slowly. He did not talk it over with his parents. Instead he went back to school and studied. In a few weeks he discovered that even algebra could be interesting, and that old Frozen Face was an interesting teacher when Charlie had studied hard enough to know what the man was talking about.

Mister deSoto never mentioned the matter again.

Getting back in the Scouts was more fun but even Scouting held surprises. Mister Qu'an, Scoutmaster of Troop Four, welcomed him heartily. "Glad to have-you, Chuck. It makes me feel good when a Scout among the new citizens comes forward and says he wants to pick up the Scouting trail again." He looked over the letter Charlie had brought with him. "A good record, Star Scout at your age. Keep at it and you'll be a Double Star, both Earth and Venus."

"You mean," Charlie said slowly, "that I'm not a Star Scout here?"

"Eh? Not at all." Mister Qu'an touched the badge on Charlie's jacket. "You won that fairly and a Court of Honor has certified you. You'll always be a Star Scout, just as a pilot is entitled to wear his comet after he's too old to herd a space ship. But let's be practical. Ever been out in the jungle?"

"Not yet, sir. But I always was good at woodcraft."

"Hum, ever camped in the Florida Everglades?"

"Well, no sir."

"No matter. I simply wanted to point out that while the Everglades are jungle, they are an open desert compared with the jungle here. And the coral snakes and water moccasins in the Everglades are harmless little pets alongside some of the things here. Have you seen our dragonflies yet?"

"Well, a dead one, at school."

"That's the best way to see them. When you see a live one, better see it first, if it's a female and ready to lay eggs."

"Uh, I know about them. If you fight them off, they won't sting."

"Which is why you had better see them first."

"Mister Qu'an? Are they really that big?"

"I've seen thirty-six-inch wing spreads. What I'm trying to say, Chuck, is that a lot of men have died learning the tricks of this jungle. If you are as smart as a Star Scout is supposed to be, you won't assume that you know what these poor fellows didn't. You'll wear that badge, but you'll class yourself in your mind as a tenderfoot, all over again, and you won't be in a hurry about promoting yourself."

Charlie swallowed it. "Yes, sir. I'll try."

"Good. We use the buddy system, you take care of your buddy and he takes care of you. I'll team you with Hans Kuppenheimer. Hans is only a Second Class Scout, but don't let that fool you. He was born here and he lives in the bush, on his father's plantation. He's the best jungle rat in the troop."

Charlie said nothing, but resolved to become a real jungle rat himself, fast. Being under the wing of a Scout who was merely second class did not appeal to him.

But Hans turned out to be easy to get along with. He was quiet, shorter but stockier than Charlie, neither unfriendly nor chummy; he simply accepted the assignment to look after Charlie.

But he startled Charlie by answering, when asked, that he was twenty-three years old.

It left Charlie speechless long enough for him to realize that Hans, born here, meant Venus years, each only two hundred twenty-five Earth days. Charlie decided that Hans was about his own age, which seemed reasonable. Time had been a subject which had confused Charlie ever since his arrival. The Venus day was only seven minutes different from that of Earth, he had merely had to have his wristwatch adjusted. But the day itself had not meant what it used to mean, because day and night at the north pole of Venus looked alike, a soft twilight.

There were only eight months in the year, exactly four weeks in each month, and an occasional odd “Year Day" to even things off. Worse still, the time of year didn't mean anything; there were no seasons, just one endless hot, damp summer. It was always the same time of-day, always the same time of year; only clock and calendar kept it from being the land that time forgot. Charlie never quite got used to it.

If Nixie found the timelessness of Venus strange he never mentioned it. On Earth he had slept at night simply because Charlie did so, and, as for seasons, he had never cared much for winter anyhow. He enjoyed getting back into the Scouts even more than Charlie had, because he was welcome at every meeting. Some of the Scouts born on Earth had once had dogs; now none of them had, and Nixie was at once mascot of the troop. He was petted almost to exhaustion the first time Charlie brought him to a meeting, until Mister Qu'an pointed out that the dog had to have some peace, then squatted down and petted Nixie himself. "Nixie," he said musingly, "a nixie is a water sprite, isn't it?"

"Uh, I believe it does mean that," Charlie admitted, "but that isn't how he got his name."

"So?"

"Well, I was going to name him 'Champ,' but when he was a puppy I had to say 'Nix' to so many things he did that he got to thinking it was his name, and then it was."

"Mum, more logical than most names. And even the classical meaning is appropriate in a wet place like this. What's this on his collar? I see, you've decorated him with your old tenderfoot badge."

"No, sir," Charlie corrected. "That's his badge."

"Eh?"

"Nixie is a Scout, too. The fellows in my troop back Earthside voted him into the troop. They gave him that. So Nixie is a Scout."

Mister Qu'an raised his eyebrows and smiled. One of the boys said, "That's about the craziest yet. A dog can't be a Scout."

Charlie had doubts himself; nevertheless he was about to answer indignantly when the Scoutmaster cut smoothly in front of him. "What leads you to say that, Al!?"

"Huh? Well, gosh! It's not according to Scout regulations."

"It isn’t? I admit it is a new idea, but I can't recall what rule it breaks. Who brought a Handbook tonight?" The Scribe supplied one; Mister Qu'an passed it over to Alf Rheinhardt. "Dig in, AIf. Find the rule."

Charlie diffidently produced Nixie's letter of transfer. He had brought it, but had not given it to the Scribe. Mister Qu'an read it, nodded and said, "Looks okay." He passed the letter along to others and said, "Well, Alf?"

"In the first place, it says here that you have to be twelve years old to join, Earth years, that is, 'cause that's where the Handbook was printed. Is that dog that old? I doubt it."

Mister Qu'an shook his head. "If I were sitting on a Court of Honor, I'd rule that the regulation did not apply. A dog grows up faster than a boy."

"Well, if you insist on joking, and Scouting is no joke to me, that's the point: a dog can't be a Scout, because he's a dog."

"Scouting is no joke to me either, Alf, though I don't see any reason not to have fun as we go. But I wasn't joking. A candidate comes along with a letter of transfer, all regular and proper. Seems to me you should go mighty slow before you refuse to respect an official act of another troop. All you've said is that Nixie is a dog. Well, didn't I see somewhere, last month's Boys' Life I think, that the Boy Scouts of Mars had asked one of the Martian chiefs to serve on their planetary Grand Council?"

"But that's not the same thing!"

"Nothing ever is. But if a Martian, who is certainly not a human being, can hold the highest office in Scouting, I can't see how Nixie is disqualified simply because he's a dog. Seems to me you'll have to show that he can't or won't do the things that a Tenderfoot Scout should do."

"Uh," Alf grinned knowingly. "Let's hear him explain the Scout Oath."

Mister Qu'an turned to Charlie. "Can Nixie speak English?"

"What? Why, no, sir, but he understands it pretty well."

The Scoutmaster turned back to Alf. "Then the 'handicapped' rule applies, Alf, we never insist that a Scout do something he can't do. If you were crippled or blind, we would change the rules to fit you. Nixie can't talk words, so if you want to quiz him about the Scout Oath, you'll have to bark. That's fair, isn't it, boys?"

The shouts of approval didn't sit well with Alf. He answered sullenly, "Well, at least he has to follow the Scout Law, every Scout has to do that."

"Yes," agreed the Scoutmaster soberly. "The Scout Law is the essence of Scouting. If you don't obey it, you aren't a Scout, no matter how many merit badges you wear. Well, Charlie?

Shall we examine Nixie in Scout Law?"

Charlie bit his lip. He was sorry that he hadn't taken that badge off Nixie's collar. It was mighty nice that the fellows back home had voted Nixie into the troop, but with this smart Aleck trying to make something of it, Why did there always have to be one in every troop who tried to take the fun Out of life?

He answered reluctantly, "All right."

"Gi

-

28:24

28:24

PukeOnABook

1 month agoRahan. Episode 175. By Roger Lecureux. The man from Tautavel. A Puke(TM) Comic.

58 -

Barry Cunningham

4 hours agoBREAKING NEWS: PRESIDENT TRUMP THIS INSANITY MUST END NOW!

53.7K114 -

LIVE

LIVE

StevieTLIVE

2 hours agoWednesday Warzone Solo HYPE #1 Mullet on Rumble

123 watching -

5:58

5:58

Mrgunsngear

4 hours ago $0.78 earnedBreaking: The New Republican Party Chairman Is Anti 2nd Amendment

4.46K5 -

LIVE

LIVE

Geeks + Gamers

3 hours agoGeeks+Gamers Play- MARIO KART WORLD

231 watching -

![(8/27/2025) | SG Sits Down Again w/ Sam Anthony of [Your]News: Progress Reports on Securing "We The People" Citizen Journalism](https://1a-1791.com/video/fww1/d1/s8/6/G/L/3/c/GL3cz.0kob.1.jpg) 29:34

29:34

QNewsPatriot

4 hours ago(8/27/2025) | SG Sits Down Again w/ Sam Anthony of [Your]News: Progress Reports on Securing "We The People" Citizen Journalism

6.93K1 -

25:12

25:12

Jasmin Laine

8 hours agoDanielle Smith’s EPIC Mic Drop Fact Check Leaves Crowd FROZEN—Poilievre FINISHES the Job

13.6K20 -

11:33:26

11:33:26

ZWOGs

12 hours ago🔴LIVE IN 1440p! - SoT w/ Pudge & SBL, Ranch Sim w/ Maam & MadHouse, Warzone & More - Come Hang Out!

6.94K -

LIVE

LIVE

This is the Ray Gaming

1 hour agoI'm Coming Home Coming Home Tell The World... | Rumble Premium Creator

42 watching -

9:42:31

9:42:31

GrimmHollywood

11 hours ago🔴LIVE • GRIMM HOLLYWOOD • GEARS OF WAR RELOADED CUSTOMS • BRRRAP PACK •

5.61K