Premium Only Content

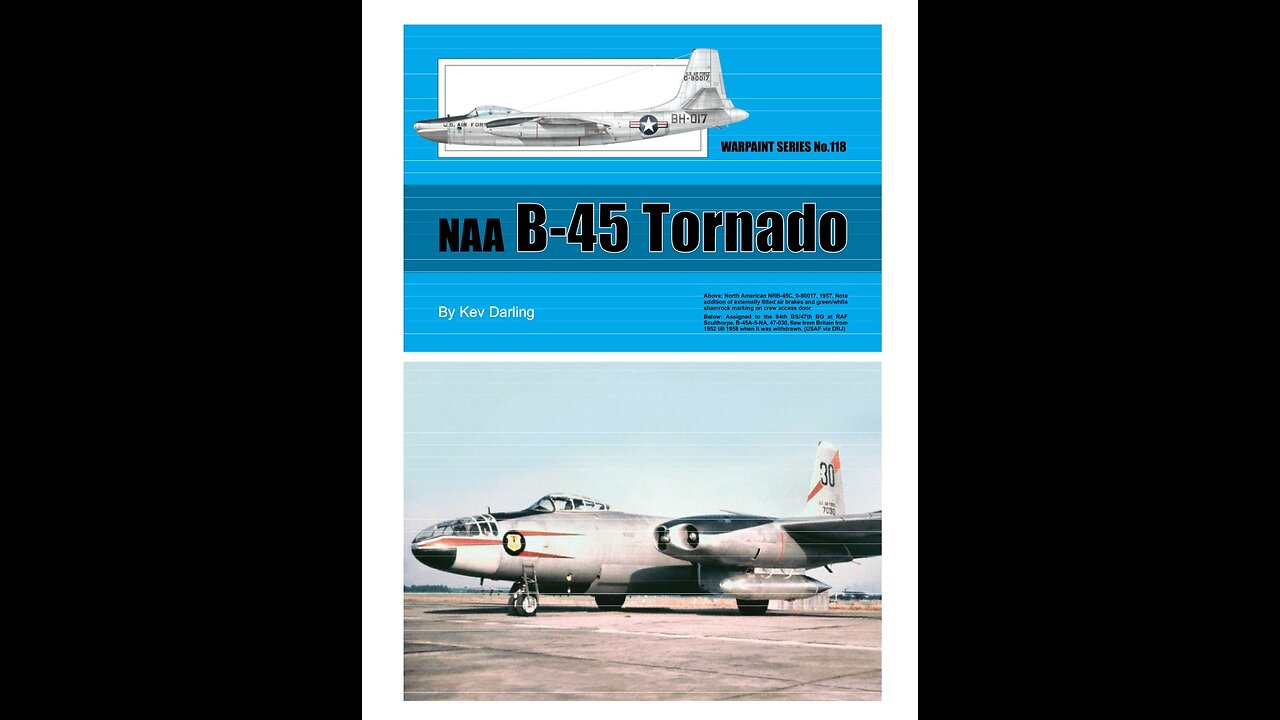

North American Aviation B 45 Tornado. By Kev Darling.

North American Aviation B 45 Tornado.

By Kev Darling.

WARPAINT SERIES Number 118.

Above: North American NRB-45C, 0 dash 80017, nineteen fifty-seven. Note addition of externally fitted air brakes and green and white shamrock marking on crew access door.

Below: Assigned to the eighty fourth BS and forty seventh BG at RAF Sculthorpe, B 45 “A-5-NA”, 47 dash 030, flew from Britain from nineteen fifty-two till nineteen fifty-eight when it was withdrawn.

North American B and RB-45 Tornado Colour Schemes.

BY RICHARD J. CARUANA.

Top: North American XB 45 Tornado, serial 45 dash 59479. Natural metal overall with Dark Olive Green anti-dazzle panels nose and engine cowlings. All lettering in black. National markings on fuselage sides, above port and below starboard wings. North American logo on nose in black over a white disc. Note smaller door size and wing pitot.

Middle: North American B 45A-1-NA Tornado, 47 dash 014, early production aircraft. Natural metal overall with Dark Olive Green anti-dazzle panels nose and engine cowlings. All lettering in black. Note fully glazed bubble canopy. Code BH 104 repeated in black below port wing.

Below: North American B-45A-5-NA Tornado, 47 dash 063, Air Force Air Test Center, based at Ladd AFB (Alaska), nineteen forty-eight to 50. Natural metal overall with Dark Olive Green anti-dazzle panels nose, engine cowlings and front section of nose framing. Insignia Red tail section. All lettering in black. National markings on fuselage sides, above port and below starboard wings. USAF in black above starboard and below port wings. AFATC badge on fuselage partly covered by the engine pods in the profile.

North American Aviation B 45 Tornado.

By Kev Darling.

Pictured over mountainous terrain is the second XB-45. During many of its test flights the crew was limited to three as the tail gun position was normally unoccupied.

With the final collapse of Japanese resistance in nineteen forty-five the United States

Army Air Force was faced with the dilemma of creating a new long range bomber force. Two of the primary machines, the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress and the Consolidated B-24 Liberator, were already out of production and would be quickly removed from the front-line inventory. This left the Boeing B-29 Superfortress as the primary long range bomber although it was already obvious that the days of the piston powered military aircraft were passing, even so two final efforts were made to use this form of powerplant, namely the Boeing B-50 and the Convair B-36.

Both types were capable of carrying the emerging crop of nuclear weapons and the British designed Gland Slam bomb. Neither of these options would make them more effective.

The answer was the jet engine and swept wings, both of which came to the attention of the USAAF from intelligence gathered in Nazi Germany during nineteen forty-three. While production of under-contract conventional aircraft continued unabated, Air Material Command instigated the development of new aircraft designs and the jet engines to power them, the latter progressing under the aegis of General Electric with the programme designations of MX-414 and MX-702 which eventually appeared as the J35 and J47 respectively. The airframe side of the equation began in nineteen forty-four when AMC contacted the primary aircraft manufacturers in the United States calling for designs using jet engines, and where possible swept wings, with a weight between 80,000 and 200,000 pounds. Four manufacturers responded, North American with the XB-45, Convair with the XB-46, Boeing with the XB-47 and Martin with the XB-48. Although all four would be offered development contracts it would be North American and Boeing who would succeed in producing aircraft that would enter operational service. The USAAF had intended to schedule a formal competition between the various contractors working on projects, although in nineteen forty-six the AAF decided to forgo the usual competition process deciding instead to sift through the provided documentation and mock-ups to select two for continued development and, hopefully, production. This selection process resulted in the Boeing and North American designs being chosen although by this time both were regarded as medium bombers. As requirements changed the B-47 remained as a medium bomber while the B-45 was redesignated as a light bomber. As a backup both the XB-46 and XB-48 were built and extensively tested although neither would progress past the prototype stage. North American’s answer was the Model 130 that was covered by Contract letter AC-5126 issued to the company on 8 September nineteen forty-four, covering the construction of three prototypes designated XB-45. As design work progressed the contract was altered slightly so that the third machine became the YB-45, the tactical bomber prototype. In order that the B-45 could enter service within a reasonable time scale North American put forward a design that drew much of its inspiration from its previous wartime designs to which were added four jet engines, paired and carried in pods under the wings, plus a bombing radar in the nose, although the wings showed much refinement using an NACA 66-215 aerofoil section at the root which tapered out to NACA 66-212 at the tip.

On the Right: This slightly different view of the second XB-45, 45 dash 59480, reveals the different skin panel tones on the unpainted airframe, it also sports the more up-to-date star and bar markings.

Right Middle: Seen just prior to its maiden flight is XB-45 45 dash 59479 sitting on the Inglewood flightline. This model had the shorter tailplane that would prove troublesome during early flight trials.

Below: This raised view of the XB-45 shows clearly the antiglare areas painted forward of the canopy and the inner faces of the engine nacelles. Also visible are the coverings outboard of the nacelles that reveal the outer wing panel attachment points. All photo credits USAF via DRJ.

On 2 August nineteen forty-six the AMC endorsed the immediate production of the B-45 followed by the negotiation and signature of Contract AC-15569 that called for an initial batch of 96 B-45A’s, North American Model N-147, plus a flying static test machine, NA Model N-130, all for a fixed cost of 73.9 million dollars. On 17 March nineteen forty-seven, the first XB-45 made its maiden flight piloted by company test pilot George Krebs. During the one hour flight from Muroc Army Airfield, California, the aircraft was flown under stringent speed restrictions as the main landing gear doors would not close properly when the undercarriage was retracted. This problem might have been avoided by installing better landing gear up-locks, however this time consuming installation was postponed as North American did not wish to delay the XB-45’s flight. Even with this restriction the XB-45’s demonstration was impressive. As a result of this successful first flight Air Materiel Command put forward an extensive test program for the three experimental airframes, each to be instrumented for a particular phase of the development and trials programme. The test programme was hit by the crash of the first aircraft on 28 June nineteen forty-nine from Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio, that killed two of the company test pilots. This accident was attributed to an engine explosion that caused extensive damage to the tailplane, this in turn causing major structural failure of that section, and as this was prior to the fitment of ejection seats the flight crew had no chance of escape.

North American B-45A-5-NA Tornado, 47 dash 082, Eighty-fourth Bomber Squadron, forty-seventh Bomber Group USAF, nineteen fifty-two. Natural metal overall with Dark Olive Green anti-dazzle panels nose and engine cowlings. Red trim, outlined in black on nose and vertical tail surfaces. All lettering in black; note ’7082’ is carried in black below US script on fin, covered by the tailplane. National markings on fuselage sides, above port and below starboard wings; ‘USAF’ in black above starboard and below port wing. Unit badge on a black disk on nose.

North American B-45A-5-NA Tornado, 47 dash 065, Eighty-fifth Bomber Squadron, forty-seventh Bomber Group USAF, nineteen fifty-two. Natural metal overall with Dark Olive Green anti-dazzle panels nose and engine cowlings. Yellow trim, outlined in black on nose and vertical tail surfaces. All lettering in black; note ’7065’ is carried in black below US script on fin, covered by the tailplane. National markings on fuselage sides, above port and below starboard wings; ‘USAF’ in black above starboard and below port wing. Unit badge on a black disk on nose.

North American B-45A-5-NA Tornado, 47 dash 087, Eighty-fourth Bomber Squadron, forty-seventh Bomber Group USAF, Sculthorpe, nineteen fifty-two. Natural metal overall with Dark Olive Green antidazzle panels nose, engine cowlings and cockpit frame. Blue trim, outlined in black on nose and vertical tail surfaces. All lettering in black; note ’7057’ is carried in black below US script on fin, covered by the tailplane. National markings on fuselage sides, above port and below starboard wings; ‘USAF’ in black above starboard and below port wing. Unit badge on a black disk on nose. Note unusual position of USAF legend on nose.

Right: Captured on an early test flight is the first XB-45. In this view the original bombardier glassed area has been replaced by a solid covering with the frames painted in. Also visible are the wingtip mounted pitot probes used to calibrate the aircraft’s primary airspeed indication system.

Right Middle: Seen just after touch-down is 45-59479 landing at Muroc Dry Lake airfield. In this view the main undercarriage doors are still extended as they had a secondary role as drag inducers; they would be closed by the pilot just prior to engine shutdown.

Below: With its nose glass house restored the first prototype undergoes refuelling outside the flight preparation hangar. Also in this view is a fire engine just in case of an incident. All photo credits USAF via DRJ.

As might be expected, the crash of the first XB-45 resulted in a thorough investigation, the primary testing being undertaken in a wind tunnel that confirmed that the aircraft had insufficient tailplane area. The lack of ejection seats in these early machines had drastically reduced the pilot’s chances of survival. In response ejection seats were installed in the other prototypes, followed by an advanced ejection system being developed for the forthcoming production aircraft. In addition future B-45’s would be equipped with wind deflectors installed forward of the escape doors from which the other two crew members, the bombardier-navigator and tail gunner, would have to bail out of in case of an emergency.

The aircraft’s tailplane area was also increased with an increase in span from 36 feet to almost 43 feet.

Although the loss of the aircraft was tragic, the flight testing of the remaining XB-45’s continued. Pilots from the Air Force took a minimal part in the initial flight tests, during which they flew approximately 19 hours, while in contrast the contractor’s crews logged more than 165 flight hours on the two remaining aircraft during 131 flights, after which the Air Force took delivery of the aircraft.

Right: This rear view of the XB-45 prototype shows the fairing over the rear gun turret position plus the location of the tail bumper. Also clearly visible is the gunner’s access door.

Centre right: Another view of the XB-45 prototype complete with the solid nose canopy and extra wingtip pitot heads. This portrait was taken during the aircraft’s early flight trials at Muroc.

Bottom right: With its gear down and locked 45 dash 59479 poses for the camera. In this view the split bomb bays are clearly shown, note the difference in size.

Bottom Left: With a Fordson tractor on one end of the towbar the XB-45 is towed out of its hangar for a day’s flying. By this time the proper three-framed glass house has been installed although the extra pitot heads still remain.

The Air Force accepted the second XB-45, 45-59480, on 30 July nineteen forty-eight, followed by the YB-45, 45-59481, on 31 August. The acceptance of both aircraft was conditional as the cabin pressurisation and air conditioning systems in both machines were incomplete, although these deficiencies were rectified later.

Once North American had completed the installation of the pressurisation and conditioning systems of the XB-45 further flight trials were undertaken by air force crews who flew a total of 181 hours in the remaining XB-45 between August nineteen forty-eight and June nineteen forty-nine, when a landing accident damaged the aircraft beyond economical repair. The remaining YB-45 had limited testing value at that time due to an initial shortage of government furnished equipment. Even so the Air Force undertook a further 82 hours of flying time after which an air force flight test crew delivered the aircraft to Wright Patterson AFB, Ohio, where the outstanding government furnished equipment was installed for bombing trials at Muroc AFB, California. Unfortunately due to excessive maintenance needs the YB-45 undertook only one test flight between 3 August and 18 November nineteen forty-nine, to evaluate the long awaited government furnished components. At the completion of its systems and bombing trials the aircraft was used for high speed parachute drops that began in Novembernineteen forty-nine. These were completed by 15 May nineteen fifty after which it was transferred to Air Training Command to serve as a ground trainer.

With the completion of the flight testing programme North American began production of the aircraft intended for service use. Even before the first Bombardment Wing was established doubts were being expressed about the type’s capability as early as June nineteen forty-eight following a meeting held in the office of General Hoyt S. Vandenberg, Air Force Chief of Staff who had assumed office on 30 April, the purpose of which was to ascertain the B-45’s value to the Air Force and its future use within the service. It was decided at that meeting that no further contracts beyond the initial one would be countenanced and that production would continue as planned up to the one hundred and ninteenth airframe, and that the funds already made available for a further contract would be used for another purpose, although this decision was later rescinded.

Top Right: Seen later in its test career is the XB-45 prototype. In this view the aircraft has been fitted with a tail gun turret although in this case the aircraft is undertaking JATO rocket testing complete with fire and thunder.

Center Right: This side-on view of the XB-45 prototype shows the clean lines of the Tornado. The type’s main failing was the underpowered engines.

Below: Surrounded by various light aircraft is the first XB-45, at this point the aircraft still requires its anti-glare paint applying to the nose and the nacelles. All photo credits USAF from DRJ.

A second contract had been issued in February nineteen forty-seven which covered further production, while a third contract was placed in June nineteen forty-eight although by this time the USAF had little desire for further aircraft, thus this tranche was later cancelled.

The use of the B-45 came under investigation by the Aircraft and Weapons Board who would hold a series of conferences at which some board members suggesting that elimination of the co-pilot position and the AN, ARC 18 liaison set installed in that position plus the tail bumper would reduce the aircraft’s empty weight by 700 pounds. Also causing confusion was the attitude of the Air Staff who were under the impression that Tactical Air Command did not consider the B-45 suitable for bombing operations, however Colonel William W Momyer, who represented TAC at these conferences, refuted this suggestion as this conclusion was probably based on previous studies by the command on the aircraft’s excessive take-off distance, although North American and the engine manufacturers were working hard to counter this deficiency.

In August nineteen forty-eight, 190 B-45’s were tentatively contracted for production, however the programme’s future was still uncertain.

Top: Seen undergoing final construction are the second and third prototypes, just visible in right of this view is the already completed first aircraft.

Bottom: The sort of take-off test crews like to undertake when showing off, the low altitude, gear and flaps up spirited departure prior to dramatic power-on climb. All Photo Credits USAF via DRJ.

In order to justify the already issued contracts Headquarters USAF inquired whether TAC required a bomber type reconnaissance aircraft for long range duties and would a version of the B-45 fulfil their needs. The answer from Tactical Air Command was delivered quickly as they did need a reconnaissance aircraft although a reconnaissance version of the B-45 would not fulfil its requirements. The command also believed that the USAF would gain greater knowledge of jet bomber operations by equipping two bomber wings with the B-45 in order to determine the tactics and limitations of the type. However the merits of these recommendations were academic as budgetary restrictions altered all future planning.

The axe that slashed the fiscal year nineteen forty-nine defense expenditures did not leave the B-45 programme completely unscathed. The initial plan for the B-45 Tornado force had called for five light bomb groups and three light tactical reconnaissance squadrons that were included in the USAF goal of seventy combat wings, an unrealistic requirement as the United States was in transition from a wartime footing to that of peace. Although the formation of the Eastern Block was giving rise to concern, the reduced USAF procurement programme was dictated by continued financial restrictions, this being reinforced by President Truman’s budget shrinkage for fiscal year nineteen fifty. The reduced B-45 programme called for only one light bomb wing plus one night tactical reconnaissance squadron, although this meant that the procurement of aircraft had to be scaled down or that a substantial number of the aircraft would have to be placed in storage upon acceptance from the factory. Neither solution was appealing, however the Aircraft and Weapons Board decided to cancel 51 of the 190 aircraft on order. The result was that 100 million dollars would be released for other crucial programmes therefore only sufficient B-45’s would be procured to equip one light bomb group, a single tactical reconnaissance squadron, plus a much needed high speed tow target squadron. In addition there would be extra B-45’s available to take care of attrition throughout the aircraft’s service life.

Five light bomb wings were included in the 70-wing force planned by the Air Force, however rejigging of the available forces to meet the reduced 48-wing target meant that the composition and deployment imposed by current funding limitations covered the formation of one light bomb wing. This wing would be allocated to the Far East Air Forces (FEAF) and would be fully equipped with B-45’s. The equipment and training path chosen by USAF was to inactivate the forty seventh Wing at Barksdale and to replace the Douglas B-26’s of FEAF’s third Light Bomb wing based at Yokota Air Base in Japan with the B-45. Maintenance personnel of the forty-seventh would also be transferred to Yokota so that FEAF would benefit from the B-45 knowledge gained by the aircraft’s first recipient.

Above: Captured on an early test flight is the second XB-45 and the first XP-86 prototype. The latter went on to achieve worldwide fame while the former nearly slipped into obscurity, even though it was the first USAF jet bomber to enter service.

Left: Giving its max, the prototype XB-45 blasts off from the Inglewood runway. With all four engines operating at full power, well for Allisons anyway, and two JATO pods blasting away, the bomber will reach high altitude in no time at all. Photo credits USAF via DRJ.

The spanner in the works of this plan was that the B-45’s could not carry sufficient fuel to fly to Hawaii, and equipping the aircraft with additional fuel tanks, a feature intended for later build B-45 models, was at the time impossible. The B-45A-1’s powered by J35 engines had a ferry range of 2,120 miles and a take-off weight of 86,341 pounds that included 5,800 gallons of internal fuel. Almost half of the fuel was contained in two 1,200 gallon bomb bay tanks and no additional fuel space was available. The following B-45-5’s powered by J47 engines had a similar take-off weight and a negligible range increase of 30 nautical miles. As both versions were limited by range problems, other solutions were investigated.

The first and only other alternative investigated was to move the required aircraft by sea, however a minimum of ten feet would have to have been removed from each of the aircraft’s wings, not a wise choice. Other forms of other sea transportation were also investigated although all research into the transport question came to a halt. In early nineteen forty-nine, the Deputy Chief of Staff for Air Materiel Command stated that the overseas deployment of B-45’s was currently out of the question for the time being as well as the immediate future. To begin with the B-45’s were not fully operational as they had no fire control or bombing equipment and the aircraft lacked a suitable bombsight, although one was undergoing development. Structural weaknesses including cracked forgings in the primary structure had been uncovered in some of the few B-45’s already flying. Until corrected these deficiencies precluded any deployment abroad. Air Materiel Command (AMC) also reported that the new J47 engine due to equip most of the B-45’s was suffering from serious problems. The engine had to be inspected thoroughly after seven and a half hours of flying time. If they were found to be serviceable the aircraft could only be flown for an additional seven and a half hours before requiring a complete overhaul. Lack of funding prevented the purchase of sufficient spare engines to ensure that the B-45’s could be kept flying if deployed overseas. AMC also anticipated difficulties in keeping those aircraft that remained in America flying even if they were close to the depots where the engines had to be inspected and overhauled. AMC also postulated that the home based B-45’s would need 900 spare engines to undertake a reasonable flying programme although none of these were available.

Left: The second XB-45 prototype, was similar to the first aircraft. In this view the bomb bay doors are open and reveal that the doors are constructed in two sections, the inner fitting inside the outer when fully open.

Below: This nose-on view of the prototype XB-45 shows that it is equipped with two pitot tubes, one per wing. Connected to separate calibration units the systems plus a chase plane would ensure that the production aircraft pitot systems would work accurately. Photo credits USAF via DRJ.

Adding to the shortage problem was that North American F-86 Sabres had first priority for the J47. The AMC report went on to say that the situation would be little altered until jet engines could be used for almost 100 hours between overhauls. This restriction meant that no jet aircraft could be stationed outside of America for at least another year.

It was not only the engines that were giving cause for concern, other systems installed in the B-45 were also causing problems. Travelling at high speeds affected the Gyrosyn flux magnetic compass and the E-4 automatic pilot when the aircraft’s bomb bay doors were open, while the emergency braking system, served by the aircraft’s main hydraulic system, was proving unreliable in operation. Also affected were the bomb racks whose mountings were poorly designed as the bomb shackles became unlocked during violent manoeuvres. The B-45’s airspeed indicator was also proving inaccurate while the aircraft’s fuel pressure gauges were both difficult to read due to needle flicker and were thus erratic. The powerplants were also posing a significant safety hazard as during start-up they often flamed out due to an imbalance in the fuel, air aspirator system that sometimes failed to work correctly. The temperature reading systems fitted to the engine jet pipes were incorrectly calibrated and thus failed to indicate the temperatures in the jet pipes while flying at high altitudes.

The aircraft’s avionics were also creating serviceability problems in the early aircraft, these centring around the AN, APQ-24 bombing and navigation radar system although few B-45’s were fitted with this system. Malfunctioning of the pressurization and conditioning system also limited the altitude at which the APQ-24’s receiver and transmitter units could operate without failing due to overheating. Allied to this was the signal modulator unit that was not pressurized thus it too limited the APQ-24 capability.

Additionally the mounting location of the radar scanner had an adverse affect on the coverage of targets especially when the aircraft was operating above an altitude of 40,000 feet. Coupled to the system unit problems were the ergonomics of the bombardier, navigator’s position as he had to attempt to manipulate two mileage control plots onto the radar screen although these were placed to the right and just behind his back. The layout of the B-45’s radar system was no better from a maintenance point of view. The USAF was still afflicted by a lack of sufficiently qualified personnel to maintain and repair the radar system thus it took up to eight hours just to remove and replace the APQ-24’s modulator unit, this being the system’s primary troublesome component.

Adding to the dismal maintenance problem were shortages of spare parts, special tools, and ground handling equipment as well as engine hoists, power units, and engine stands.

Right: This is the third Tornado prototype, seen sitting on the flight line with its main undercarriage doors down. Unlike the first prototype this machine featured the extended tailplane which improved the type’s stability.

Below right: The final B-45 prototype, was retained for trials purposes for which purpose it was subject to the various modification programmes applied to the operational fleet.

Below: This overview of the second prototype shows clearly the extended tailplane span. In common with the other prototypes the aircraft retains a fighter type pilot’s canopy and the three-frame nose glazing.

The Nuclear Tornado.

Prior to nineteen forty-nine the USAF had never seriously considered the tactical employment of nuclear weapons apart from their use for strategic air warfare. Allied to this was that early nuclear weapons were costly and given the difficulty in producing fissionable material would remain few in number for many years. The change to this policy was the development and large quantity production of small tactical nuclear weapons, thus the USAF earmarked such weapons again for strategic use only, especially as warheads for proposed guided missiles. Although the Air Staff seemed happy with this strategy the Weapons Systems Evaluation Group conducted a study on the use of the nuclear weapon on tactical targets, including the effect of such a weapon on such targets as troops, aircraft, and ships massed for offensive operations plus naval bases, airfields, naval task forces, and heavily fortified positions. The study was concluded in November nineteen forty-nine and found that tactical nuclear bombs would be effective on all targets. While of an informal nature, the Weapon Systems Evaluation Group’s study was noted by the Air Staff although no action was taken until mid-nineteen fifty, when the outbreak of the Korean War underlined the weakness of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization forces should the Russians ever decide to seize the opportunity to attack Europe. These realisation forced events to move rapidly. Overall command and responsibility for these weapons would remain under the control of Strategic Air Command, however the use of nuclear weapons would become Air Force-wide.

Top: North American B-45A-5-NA Tornado, 47-057, eighty-sixth Bomber Squadron, forty-seventh Bomber Group USAF, nineteen-fifty-two. Natural metal overall with Dark Olive Green anti-dazzle panels nose and engine cowlings. Red trim, outlined in black on nose and vertical tail surfaces. All lettering in black; note ’7057’ is carried in black below US script on fin, covered by the tailplane. National markings on fuselage sides, above port and below starboard wings; ‘USAF’ in black above starboard and below port wing. Unit badge on a black disk on nose.

Middle: North American B-45A-5-NA Tornado, 47-055, eighty-sixth Bomber Squadron, forty-seventh Bomber Group, England, nineteen-fifty-two. Natural metal overall with Dark Olive Green anti-dazzle panel, canopy frame and engine cowlings. Blue trim, outlined in black on nose and vertical tail surfaces. All lettering in black. Note ’7055’ is carried in black below US script on fin, covered by the tailplane. National markings on fuselage sides, above port and below starboard wings; ‘USAF’ in black above starboard and below port wing. Unit badge on a black disk on nose.

Bottom: North American B-45A-5-NA Tornado, 47-039, Eighty-fifth Bomber Squadron, forty-seventh Bomber Group, nineteen-fifty-three. Natural metal overall with Dark Olive Green anti-dazzle panels nose and engine cowlings. Yellow trim to nose and vertical tail surfaces, outlined in black. All lettering in black. National markings on fuselage sides, above port and below starboard wings; USAF in black below port wing. Unit badge below cockpit.

Above: The North American flight line could be a busy place as this view shows. Here B-45A 47-062 sits alongside an F-86 from the same manufacturer while other B-45’s undergo pre-flight checks. The nearest machine has flap set-up gauges on its upper wing.

Center: The second production aircraft. It was retained for trials use, mainly at Wright-Patterson AFB.

Bottom: Complete with large buzz numbers under the wings 47-011 undertakes a pre-delivery flight. The aircraft served with the forty-seventh Bomb Wing before being retired for spares recovery purposes. Of note is the four-digit tail number as used by all the operational aircraft. All photo credits USAF via DRJ.

In support of this policy change the Air Staff, on 14 November Nineteen fifty, directed TAC to develop tactics and techniques for the use of nuclear weapons in tactical air operations.

Tactical Air Command had originally been part of the Continental Air Command when the USAAF became USAF in Nineteen forty-eight, although it gained major command status in December Nineteen fifty.

The directive received a further push in January Nineteen fifty-one when an Air Staff programme was outlined to ensure that TAC would become nuclear capable as soon as possible. The B-45 would be at the forefront of the new plan as the aircraft also became the first light bomber fitted for nuclear weapons delivery. Turning the TAC nuclear capability into a reality was the secrecy surrounding the production of the first weapons that created difficulties for both the aircraft manufacturer and the AAF. Due to the dissemination of incorrect information the B-45 could not have been used as a nuclear weapons carrier without major internal modifications to the bomb bay as the main spar that travelled across the aircraft’s bomb bay limited the size of weapon that could be carried.

Right: The different metal colors of the B-45 are revealed in this overview of 47-011. Unlike later build machines this aircraft retained the fighter type canopy fitted to the prototypes plus the original three-frame nose glazing.

Center: Another view of an early production machine, this time 47-014. In this view the aircraft has its bomb bay doors fully open. Just visible is the fuel dump vent just aft of the tail bumper.

Below: Prior to entering service with the forty seventh Bomb Group B-45A-NA-5 47-025 was used to clear the type for conventional weapons usage. Here clutches of 500 pound bombs depart the rear bomb bay although some reports state that the type was unstable during bomb drops. All photo credits USAF via DRJ.

Making the task of Tactical Air Command more difficult was the decision to extend the use of nuclear weapons to all combat forces, thus the B-45’s acquired by TAC would no longer remain under direct control.

This also meant that TAC would have too few aircraft to develop tactical operational techniques with the new weaponry. Further complications arose when the smaller, safer and lighter nuclear bombs entered the stockpile earlier than expected, again intensive secrecy had accompanied the new developments. These changes meant that the B-45 would be unable to carry any of the new weapons without first undergoing further extensive modification to carry them.

In December Nineteen fifty some sixty B-45’s were earmarked for nuclear weapons delivery duty, this consisting of three squadrons of 16 aircraft each, plus 12 attrition machines. This total would be reduced to forty aircraft in mid Nineteen fifty-one although it was increased again in mid Nineteen fifty-two, when fifteen other B-45’s were added to the special modification programme. The Air Staff directed AMC to modify a first lot of 9 aircraft to carry the small bombs for which designs were then available. This initial project would allow for suitability tests by the Special Weapons Command that was established in December Nineteen forty-nine, later re-designated Air Force Special Weapons Center being assigned to Air Research and Development Command in April Nineteen fifty-two. However the diversion of these aircraft meant that TAC had fewer test aircraft to undertake its new tasks. To speed up the development programme five of the nine aircraft would be equipped with the AN-APQ-24 bombing and navigation system while the remaining four would be fitted with the AN-APN-3 Shoran navigation and bombing system, plus the visual Norden M9C bombsight. North American would bring the nine aircraft up to the required special weapons configuration for a total cost of 512,000 dollars.

Above: Seen lifting off under full power is B-45A 47-026 complete with a solid nose and a fully framed canopy. By this time the buzz number under the wing had been replaced by USAF titling.

Center: With NAA engineers attending to some final details RB-45C 48-011 would be cleared for service use with the Nineteenth SRS.

Bottom: The third prototype was used for numerous system trials prior to the B-45 entering service with the USAF. In this view the aircraft has both its nose gear doors open plus the main gear doors.

By mid Nineteen fifty-one the programme for operational use of the B-45 in possible nuclear operations was finally established. The aircraft involved in this programme were code-named Backbreaker and included, in addition to the B-45 light bombers, 100 Republic F-84 Thunderjet fighter bombers. As the availability of modified B-45’s increased the programme’s status was accelerated so that it became second only to a concurrent and closely related modification program involving various SAC bombers. In August Nineteen fifty-one the programme received further impetus as the Air Staff confirmed that nuclear capable modified B-45’s, equipment, and allied support would be supplied to enable units of the forty-seventh Bombardment Wing in the United Kingdom to achieve a proposed operational nuclear capability by April Nineteen fifty-two. In addition to the first batch of nine aircraft, the programme would be extended to cover a further 32 B-45’s, the latter modification programmes cost being set at 4 million dollars. One B-45A was destroyed by fire in February Nineteen fifty-two and not replaced thus reducing the available total from 41 to 40 aircraft. Of the 4 million dollars allocated to the project some of the funds were diverted from other Tactical Air Command projects that were later cancelled. The Air Staff requested that sixteen of the aircraft be ready by 15 February Nineteen fifty-two, while the remainder should be available by 1 April. The modifications applied to those airframes chosen for the Backbreaker programme required extensive reworking. Equipment had to be installed in the aircraft for carrying three different types of nuclear weapons which in turn necessitated some structural modifications to the bomb bay. Special carrying cradles were provided for each type of weapon while special hoisting equipment was required for loading each type into the Backbreaker B-45’s. To support the delivery of each weapon a large amount of advanced electronics equipment had to be installed, replacing the standard equipment, while further modifications added new defensive systems and extra fuel tanks to the airframe. North American and the Air Materiel Command’s San Bernardino Air Materiel Area, in San Bernardino, California, shared the modification responsibilities for the B-45 Backbreaker program. In early Nineteen fifty-two the nine B-45’s, already modified to a limited Backbreaker configuration by AMC and North American, were returned by TAC to San Bernardino for completion of the modifications, thus bringing them up to the same standard as the main tranche. Reworking of the other 32 B-45As, later reduced by one after an accident, also took place at the San Bernardino Air Materiel Area during the first three months of Nineteen fifty-two with North American being responsible for furnishing all necessary modification kits. Fortunately good co-operation between the AMC, North American and equipment subcontractors meant that the entire modification programme was completed without significant delays. Much of the electronic and support components required for the Backbreaker configuration were of a new and advanced design and were in very short supply.

Right: By the time B-45C 48-005 rolled off the production line the nose canopy was fitted with four frames as standard. Here 48-005 awaits its next flight at Edwards AFB.

Below: Never used by the USAF this machine, 47-014, was used for experimental purposes for which it was designated EB-45A. Not often seen is the nose entrance ladder used by the pilots and the bombardier-navigator to enter the aircraft.

The requirement for the AN-APQ-24 radar for the B-45 placed it in direct competition with Strategic Air Command programmes. As delivered the replacement radars were not configured for the delivery of nuclear weapons so those few available AN-APQ-24 sets had to be modified to the new configuration. SHORAN units were also in short supply so a quantity had to be diverted from Far East Air Force’s and Tactical Air Command’s B-26 upgrade programme. Other challenges facing those undertaking the Backbreaker programme centered around shortages of minor equipment items that were required to integrate some of the aircraft’s systems. Some of the new equipment could not be installed before connectors were manufactured whilst other much needed components simply did not exist. One of the major omissions was the bomb scoring unit which consisted of a series of switches and relays that controlled the release of specific weapons in concert with the radar bombing system. As no such device existed each unit had to be manufactured at AMA San Bernardino. The Air Materiel Area also made parts for the A-6 chaff dispenser including a removable chute for easier maintenance. North American also manufactured special fuel flow totalizers for the fuel system in order to control the rate and amount of fuel supplied to the engines; this unit also assisted in the supply of correct contents gauging to the crew whilst maintaining a balanced fuel feed. North American was also responsible for the manufacture of special equipment to integrate AN-APG-30 radar with the rest of the Backbreaker B-45’s tail defense system The Fletcher Aviation Corporation of Pasadena, California, was responsible for the production of the extra fuel tanks while AMC’s Middletown Air Materiel Area in Middletown, Ohio manufactured the special slings that were required to carry some of the new weapons.

While the Backbreaker modifications were extensive the AMC and the manufacturers also had to cope with various existing engine problems which needed curing as the bomber modification would be useless without them. A report by the General Electric Company field representative advising the forty-seventh Bombardment Group throughout most of Nineteen fifty-one indicated that the J47’s powering the Backbreaker aircraft would share some of the flaws of the type’s previous power plants. The J47’s available at that time suffered from turbine failures similar to those that had afflicted the earlier Allison built J35’s. Also subject to failure were the turbine tail cones that fractured when the J47 overheated. Flight stresses also caused oil leaks that meant that the engines had to be removed for repairs and ground test runs, all of which required a lot of man-hours to rectify. While the USAF did not expect any new engine to be problem free from the outset, the urgency surrounding the Backbreaker modification programme made these difficulties more significant. In July Nineteen fifty-two the Air Force decided to increase the number of nuclear capable B-45 aircraft by a further fifteen aircraft. The proposed configuration was that of the Backbreaker aircraft plus improvements based on experience and in-service modifications. The primary updates covered the Backbreaker aircraft’s tail defense system and the fuel flow totalizer that had been manufactured for the first 40 Backbreaker B-45’s, although they had not been installed due to production delays. Another important change required relocation of the carrier supports required by a specific type of nuclear weapon be moved into the forward bomb bay thus allowing for the installation of a 1,200 gallon fuel tank in the rear bay. The fitment of this extra fuel tank would give the aircraft a useful increase in range of approximately 300 nautical miles. By September Nineteen fifty-two after a design conference with North American the USAF decided on the improved Backbreaker configuration and established a programme for procurement and installation of the necessary modification kits. The Air Force then allocated 2.2 million dollars for modification of the fifteen additional B-45’s plus a further 3 million for retrofit of the first 40 Backbreaker aircraft. The primary depot allocated to this task was the San Bernardino Air Materiel Area who would undertake the new modifications and would also be responsible for the provision of all necessary kits for the Backbreaker retrofit, although these would be done in the field by unit engineers. Initially it was thought that the modification programme would proceed on time as it involved less work than the original Backbreaker modification. However the programme was subject to slippage as during the second half of Nineteen fifty-two the Air Materiel Command was in the process of transferring certain responsibilities from its headquarters to the various air materiel areas.

Page 16:

Above: B-45A-5-NA 47-021 was bailed to NACA straight from the manufacturers. Its career was short, the aircraft crashing a few months later in August Nineteen fifty-two.

Center: B-45C Tornado 48-002 would never enter front line service with the USAF being retained as a testbed by the manufacturers. Re-designated as the EB-45C the aircraft was lost in Nineteen fifty after suffering structural failure.

Below: B-45A-5 47-039 was operated by the forty-seventh Bomb Group and would be lost in a crash in August Nineteen fifty-three. Of note is the crew access ladder and the outward opening door, the prototype doors opened inwards.

This resulted in delays in processing engineering data and purchase requests, which in turn delayed the manufacture of the field modification kits and their delivery by North American. Further difficulties occurred at North American as the contractor was no longer tooled for constructing the B-45 and was working to capacity on other products. As a result of these deficiencies, modification kit deliveries did not begin until July Nineteen fifty-three thus pushing installation back four months. In September Nineteen fifty-three the USAF added a further three B-45’s to the modification programme, however as two of the original conversion batch aircraft had been retired and one had crashed the total still remained at fifteen. Completion of the conversion programme was delayed until March Nineteen fifty-four as later build machines were slotted into the programme to compensate for a lack of available B-45As.

While the Backbreaker modifications and retrofits enabled the B-45’s to handle several types of the smaller nuclear weapons, the modified aircraft were unable to carry and deliver the special weapons needed for the tactical interdiction mission, so in Nineteen fifty-three, due to the increasing availability of nuclear weapons, the USAF thought of transferring this responsibility from SAC to TAC. In the event the situation remained unchanged as neither command had the type of aircraft available to carry out the task until the Douglas B-66 Destroyer became available.

The “N-A-A” B-45 Tornado described.

The North American B-45 ”A-1”, “A-5” and C models of the Tornado were described as land based, four-engine jet propelled bombers that were designed to operate at high speeds and at high altitudes. The aircraft was tasked with the tactical bombing of both land and sea targets. Should the B-45 be required to undertake longer range attacks extra fuel capacity could be installed in the bomb bay, while the B-45C could be fitted with external wingtip tanks. The basic crew consisted of a pilot, co-pilot, who also acted as the radio operator, bombardier-navigator and the tail gunner. The two pilots were mounted on ejection seats while the other crew members bailed out through hatches in the nose and tail, both being provided with wind deflectors. The crew’s duties saw the pilot in the forward seat under the canopy having all the controls to hand to fly the aircraft while the co-pilot acted mainly as the radio operator, although his position was equipped with basic flight controls, basic engine controls, elevator trim controls and the emergency braking system although no controls were provided for the fuel and hydraulic systems nor for the undercarriage, flaps, aileron and rudder trim tabs.

The fuselage of the B-45 was constructed in three sections, the major section stretching from the pilot’s front bulkhead to the rear fin post, aft of which was the gunner’s compartment. This section consisted of seven primary frames supported in turn by further, lighter frames, these being riveted to load bearing longerons and stringers all being covered by alloy skinning.

Right: Seen soon after rollout is the XB-45 prototype being worked on by NAA flight test engineers. In this view the fighter type pilot’s canopy is clearly visible as is the original bombardier’s troublesome glass-covered nose section. Due to manufacturing problems many of the operational systems were missing from this aircraft.

Below: This underside view of 45-59479 clearly shows the panel lines and the flight control surfaces. Note the different metal colors. Photo Credits: USAF via DRJ.

Across the bomb bay was the main spar, with secondary spars fore and aft. Forward of the pilot’s front bulkhead was a separate nose section that housed the bombardier-navigator under whom was carried the radar scanner. Over the upper section was extensive framing that carried the glazing that illuminated the compartment. Attached to the rear of the main fuselage was the final section which housed the gunner’s compartment and his weaponry. All crew areas were pressurized and fitted with air conditioning systems. Unlike earlier bombers, access between the fore and aft compartments was only possible when the aircraft was depressurised, the bomb doors were shut and the bay was empty.

The wings were constructed around a primary main spar with secondary spars carried fore and aft. Wing shape was provided by nose ribs, interspar ribs, many with cutouts for the fuel tanks, with stressed skinning overall. Extra strengthening was provided at the nacelle mountings for the engines and on the main spar at the main undercarriage mounting points. The wings were attached to the fuselage spar sections using bolts fitted both vertically and horizontally. On the wing trailing edge were carried the flap sections, these being mounted either side of the engine nacelles, while the outer section of each wing was the mounting point for the aileron. The flap sections and ailerons were constructed around a single spar that had nose ribs forward and further ribs aft forming a distinct taper, all were alloy skinned. The tailplanes were of twin-spar construction and were similar in construction to the wings; at their trailing edge were the elevators that were similar in construction to the ailerons. The fin and rudder were similar in construction to the other flight surfaces, and all were fitted with trim tabs.

The flight control surfaces were conventional in nature although all surfaces were fitted with hydraulic power boosters. The ailerons and elevators were controlled using a control wheel that incorporated a push-to-talk radio button, the auto pilot release, the nose wheel steering trigger switch and the elevator trim control switch. For access to the rudder pedals and other equipment the pilot’s control wheel column could be disengaged using a release catch. The co-pilot’s control wheel was similarly equipped with switches and could also be folded away as could the rudder pedals. To stop the control surfaces moving in an uncontrolled manner the flight control system was fitted with a locking unit in the cockpit although it could not be engaged while the hydraulic booster units were shut down. The trim tabs fitted to the flight control surfaces were electrically powered, being positioned using the single control stick mounted at the pilot’s position. The elevator and rudder boosts were powered by a pair of electrically powered hydraulic pumps, both pumps were used to drive the elevators while the rudder used only a single pump. In the first batch of aircraft, low speed handling control was courtesy of a bungee providing an elevator down-force. In normal flight the bungee force was cancelled out by use of the trim tabs. In the B-45 “A-5” and the B-45C the low speed handling was managed by the downward cant of the jet pipes and spring tabs on the elevators. Instead of using electrically driven pumps the aileron boost system used pressure derived from the engine driven pumps drawn from Numbers one and three engines, however on the later build machines the hydraulic pumps from the other two engines were used to drive the surfaces.

Above: B-45C 48-001 was retained by North American for trials use although it was later lost in an accident.

Left: Destined to serve with the manufacturers amongst other users for trials work, RB-45C 48-037 was finally retired to Norton AFB in December Nineteen fifty-seven.

Aileron boost became effective as soon as the engines started, however should any of the engines powering the aileron boost system undergo a power change or be shut down for any reason there was a corresponding increase in aileron forces.

During normal flight enough hydraulic power was available to keep the aileron boost powered up when the engine was windmilling, however once speed dropped to 140 mph or lower the bypass valve in the windmilling engine’s hydraulic system switched into the open position, making the system inoperative. When this happened the aileron forces became heavier as control had reverted to fully manual.

Also driven by the hydraulic system were the wing flaps that consisted of four separate sections, located between the fuselage and the engine nacelles and between the nacelles and the ailerons. Selectable flap positions were available between fully up and fully down at forty degrees. Intermediate positions could be selected by the use of the selector lever in the pilot’s cockpit. Power for the flaps was supplied by the engine driven pumps. Emergency flap could be lowered using the emergency lowering system which diverted flow from the emergency pump to the flaps. Only the down selection was available using this system, no up selection was possible. Hydraulics also powered the undercarriage system, the main undercarriage units retracted inwards towards the wing roots while the nose wheel assembly retracted aft into its bay. As the main gear retracted into the bays the wheel brakes came on automatically to stop the wheels spinning. The nose wheel unit also incorporated a steering unit that also acted as an anti shimmy unit when disengaged. The B-45 was also fitted with a hydraulically driven tail skid which automatically extended and retracted in sequence with the undercarriage. During approach the main undercarriage fairing doors remained open to increase drag for deceleration during landing. Should the undercarriage selector be placed in the down position during landing the main gear doors would close automatically on touchdown, however should further drag be needed during the landing roll the selector had to be left in the neutral position although it had to be returned to down prior to engine shut-down.

In common with many aircraft the B-45 would normally be fitted with ground locks and a safety cover over the selector to prevent inadvertent retraction. Indication of the undercarriage position was courtesy of a light sequence, thus green indicated fully down and locked, red indicated unlocked while amber indicated that the gear was in transit. Should there be a failure in the hydraulic system the undercarriage could be lowered using the emergency system. This was activated using a hand pump located behind the bombardier’s position. The initial cycles released the undercarriage gear and door uplocks, after free falling the legs were pumped into the locked position. In the later build aircraft the hand pump was replaced by two switches located close to the forward bomb bay bulkhead in the rear of the pilot’s cockpit.

Selection of door open and gear down would see the locks disconnected mechanically after which the undercarriage dropped down into the locked position. Other hydraulic units driven by the aircraft’s systems included the nose wheel steering unit that would only operate when the nose wheels were on the ground and the shock absorber jack was compressed. When operated by the pilot using the switch on the control wheel, this allowed the pilot to move the unit 45 degrees either side of the centreline. For ground movement the steering unit and antishimmy unit could be disconnected by removing a pin thus ensuring these units were undamaged during ground movements. The aircraft’s brakes were controlled using the toe pedals on the rudder pedals.

Top: North American B-45C-1-N-A Tornado, 48-001, retained by North American for trials. Black anti-dazzlepanels nose and engine cowlings. All lettering in black. National markings on fuselage sides, above port and below starboard wings. USAF in black above starboard and below port wings.

Center: North American B-45C-1-NA Tornado, 48-010, Eighty-fifth Bomber Squadron, forty-seventh Bomber Group USAF, Nineteen fifty-two. Natural metal overall with black anti-dazzle panels nose and engine cowlings. Yellow trim, outlined in black on nose and vertical tail surfaces. All lettering in black; note 7065 is carried in black below US script on fin, covered by the tailplane. National markings on fuselage sides, above port and below starboard wings; USAF in black above starboard and below port wing. Unit badge on a black disk on nose. Preserved at Wright Patterson Air Force Base Museum.

Bottom: North American B-45A-1-NA Tornado, 47-0008 bailed to North American as a test aircraft. Natural metal overall with Dark Olive Green TT-C-595 3406 anti-dazzle panels nose and engine cowlings. Black wing, tailplane, and engine air intakes leading edges; black lettering. Red bands around fuselage, vertical tail surfaces, and wing and tailplane undersides. National markings on fuselage sides, above port and below starboard wings. USAF in black above starboard and below port wings. Shown as in September 1981 at China Lake for restoration for Castle Air Museum.

Top: Bailed to Northrop Aircraft as an EDB-45C 48-005 was used as a drone control test aircraft on behalf of the USAF. Note the lack of wingtip tanks and the cone over the tail gun turret position.

Bottom: Photographed while still based at Langley AFB is this group of B-45’s belonging to the forty-seventh BW. In this view the rear gunner’s position is clearly shown. Visible is the remotely operated gun turret, minus guns, plus the sighting mechanism in its clear dome. Also shown are the rear escape hatch and deflector panels.

For emergency use there were emergency levers at both pilot’s positions and that at the pilot’s position could be used as a parking brake.

The bomber versions of the B-45 were fitted with two different types of engine, the Dash One was powered by four Allison J35 engines mounted in pairs under each wing.

Two variants were used, these being the J35-A-9 and the J35-A-11. The subsequent Dash Five and B-45C were powered by either the J47-GE-7, 13 or the J47-GE-9, 15 all of which were manufactured by General Electric. Each Allison power plant was provided with a pressure type oil system that contained 12.7 gallons of usable fluid. Monitoring of tank contents was via gauges mounted on the pilot’s panel. The oil system provided for the GE engines was similar in operation although the tank content was reduced to 6.7 gallons of usable fluid.

The B-45 could be fitted with external tanks mounted under the engine nacelles containing water methanol and injection of this mix into the engines could be used to improve take-off performance. To use the water injection system the flaps needed to be set to 20 degrees while the trim tabs had to be set at zero.

The fuel system installed in the B-45 consisted of eight fuel tanks made up of 22 cells interconnected to make up the groups. Each wing group under normal circumstances fed the engines on that side of the aircraft although in an emergency a fuel system cross feed line could be opened to supply fuel to the engines on the opposite wing. When the jettisonable wing tanks, each holding 1,250 US gallons, were installed they were referred to as Number four fuel tank. Under normal circumstances each tank fed the relevant pair of engines although should one become inoperative the remaining tank could be switched to feed all four engines. Unlike the main system the wingtip tanks had no gauging, however each had an empty light that illuminated when their contents had been used. All fuel tanks were fitted with booster pumps as were the bomb bay tanks when fitted. When a single tank was fitted in the bomb bay both fuselage pumps were connected to the tank although when two tanks were installed only one pump was fitted to each tank. As these pumps had a greater output than the wing tank pumps the bomb bay tanks had to be used first. Should circumstances warrant it the bomb bay tanks and or bombs could be jettisoned using the salvo panel located at the pilot’s position.

However there were provisos to this instruction as the 310 US gallon tanks could not be jettisoned when the aft bomb bay shackles, Type D-7, for the 2,000 and 4,000 pound bombs were fitted. The B-45 was also capable of carrying a 1,200 US gallon tank in the bomb bay but the pilot was warned not to open the bay doors as damage could occur to the tank, although the pilot was allowed to open them when the tank was full or it required jettisoning. If fitted the wingtip tanks could also be jettisoned using the controls located at the pilots’ stations either by using a mechanical release or the salvo panel. Refuelling the B-45 was through a single pressurized refuel point located on the left hand side of the fuselage aft and below the trailing edge of the wing.

The B-45 electrical system fitted to the earlier build machines used four engine driven 28 volt DC generators which acted as combination generators and starter units. Once the engines were running the 115 volt “A-C” alternators fitted to Numbers one and three engines were available for use via a selector switch in the cockpit. The electrical system provided power to the lights, booster pumps, engine starters, fuel shut-off valves, armament and communications equipment, bombing system, camera, automatic pilot, nose wheel steering, trim tabs, rudder-elevator boost, ATO ignition units, air conditioning, pressurization, emergency hydraulic pump, fire detectors and extinguisher, escape deflector flaps plus electrical instrumentation and transmitters.

On later build aircraft electrical supplies also controlled the sequence valves for the landing gear doors plus the inverters for the operation of the automatic pilot, radar equipment and drift meter. The alternators in all versions operated the radar equipment, heaters for windscreen anti-icing, defrosting and surface control boost systems.

The aircraft was well equipped with both interior and external lighting. The latter included the navigation lights that could be used for signal purposes; when the tip tanks were fitted they had navigation lights fitted as the wing lights were obscured. Fuselage identification lights were also fitted above and below, these too could be used for signaling.

Formation lights were also installed for the rare occasions when this was practiced, other external lights included a landing light mounted in the front of the left engine nacelle, and a taxi light was mounted on the left hand undercarriage leg. The internal lighting in the aircraft included lighting for all the panels at the crew stations, lights in the passage way alongside the pilots towards the nose compartment, while in the bomb bay and unpressurised compartments there were lights to assist the ground crew in their maintenance tasks. A further light was installed in the nose wheel bay, visible through a window at floor level in the pilot’s compartment, used to check the position of the leg.

Above: The fate of many an NAA Tornado, to lie battered and abused on the side of an airfield somewhere while fire and rescue crews practiced their arts. This particular aircraft is 47-056 late of the forty-seventh BW. Photo Credit: Trevor Jones.

Bottom Left: RB-45C 48-012 is seen here undergoing preparation for flight prior to being delivered to the USAF. In service the aircraft flew from Alconbury on reconnaissance duties before ending its days as a rescue trainer in France. Photo Credit: USAF via DRJ.

Avionics.

One of the major avionics systems fitted to the B-45 was the auto pilot, the Type E-4, managed by a stowable control panel at the pilot’s position. The auto pilot could be used in conjunction with the automatic approach equipment, this being the airborne part of the instrument landing system. On the later build aircraft the auto pilot could also be engaged with the radar navigation system through a steering connector in the bombardier’s compartment, when engaged it allowed the bombardier to steer the aircraft on its bombing run. The main limitation to the auto pilot was that it could only be engaged when in level flight as engagement in a turn would cause the aircraft to divert off course. When the auto pilot was engaged the side stick controller could be used to fly the aircraft. The auto pilot could also be managed under barometric control for height maintenance although this could not be used unless the elevator servo was engaged.

The B-45 was also fitted with an automatic approach control system that allowed the pilot to follow the radio beams generated by the localized approach glide path generator. To engage the approach control the auto pilot needed to be disengaged while the controller needed to be selected to either localizer or approach. As the aircraft intercepted the localizer beam it would turn to follow the beam down

-

33:20

33:20

PukeOnABook

16 days agoRahan. Episode 172. By Roger Lecureux. Rahan against time. A Puke(TM) Comic.

85 -

2:52:45

2:52:45

TimcastIRL

4 hours agoTrump Admin ARRESTS Boulder Terrorists ENTIRE FAMILY, Preps Deportations | Timcast IRL

157K88 -

2:40:48

2:40:48

RiftTV/Slightly Offensive

6 hours agoBig, Beautiful SCAM? Elon FLIPS on Trump for WASTEFUL Bill | The Rift | Guests: Ed Szall + Matt Skow

42.8K9 -

LIVE

LIVE

SpartakusLIVE

5 hours agoSpecialist TOWER OF POWER || Duos w/ Rallied

493 watching -

3:24

3:24

Glenn Greenwald

4 hours agoPREVIEW: Sen. Rand Paul Interview Exclusively on Locals

84.8K47 -

LIVE

LIVE

VapinGamers

3 hours ago $0.05 earned⚔ 🔥 Blades of Fire - Game Review and Playthru - !game !rumbot #sponsored

305 watching -

LIVE

LIVE

ZWOGs

8 hours ago🔴LIVE IN 1440p! - Max Payne 3, Halo Infinite, Marvel Rivals, Splitgate 2, & Maybe Helldivers 2 - Come Hang Out!

31 watching -

1:14:00

1:14:00

The Daily Signal

4 hours ago🚨LIVE: Democrats Champion Illegals Amid MORE ICE Arrests

42.2K1 -

LIVE

LIVE

RaikenNight

3 hours ago $0.10 earnedFinally got my surgery scheduled! Playing Tainted Grail

40 watching -

LIVE

LIVE

This is the Ray Gaming

3 hours ago $1.19 earnedWelcome to Rumble This is the Ray Gaming

159 watching