Premium Only Content

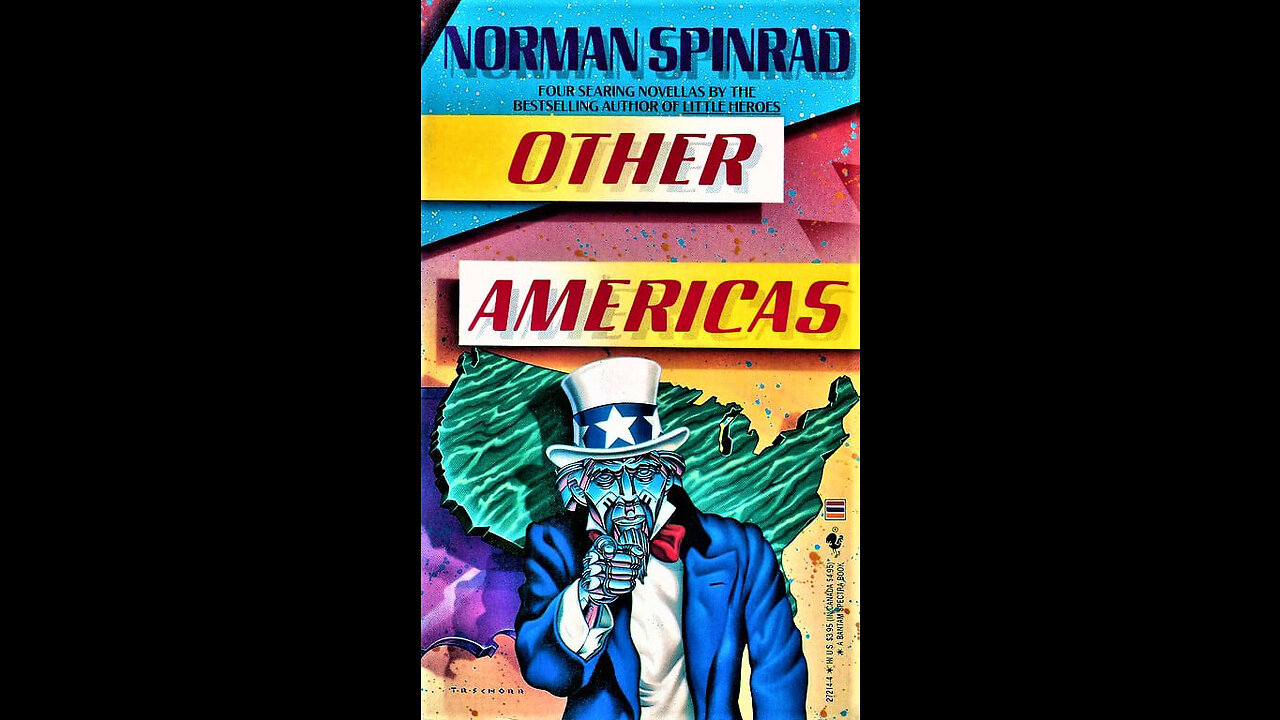

THE LOST CONTINENT. Norman Spinrad A Puke(TM) Audiobook

THE LOST CONTINENT.

I felt a peculiar mixture of excitement and depression as my Pan African jet from Accra came down through the interlocking fringes of the East Coast and Central American smog banks above Milford International Airport, made a slightly bumpy landing on the east-west runway, and taxied through the thin blue haze toward a low, tarnished-looking aluminum dome that appeared to be the main international arrivals terminal.

Although American history is my field, there was something about actually being in the United States for the first time that filled me with sadness, awe, and perhaps a little dread.

Ironically, I believe that what saddened me about being in America was the same thing that makes that country so popular with tourists, like the people who filled most of the seats around me.

There is nothing that tourists like better than truly servile natives, and there are no natives quite so servile as those living off the ruins of a civilization built by ancestors they can never hope to surpass.

For my part—perhaps because I am a professor of history and can appreciate the parallels and ironies! not only feel personally diminished at the thought of lording it over the remnants of a once-great people, but it also reminds me of our own civilization’s inevitable mortality.

Was not Africa a continent of so-called “underdeveloped nations” not two centuries ago when Americans were striding to the moon like gods? Have we in Africa really preserved the technical and scientific heritage of Space-Age America intact, as we like to pretend? We may claim that we have not repeated the American feat of going to the moon because it was part of tired overdevelopment that destroyed Space-Age civilization, but few reputable scientists would seriously contend that we could go to the moon if we so chose.

Even the jet in which I had crossed the Atlantic was not quite up to the airliners the Americans had flown two centuries ago.

Of course, the modern Americans are still less capable than we of recreating twentieth-century American technology.

As our plane reached the terminal, an atmosphere-sealed extension ramp reached out creakily from the building for its airlock.

Milford International was the port of entry for the entire northeastern United States; yet, the best it had was recently obsolescent African equipment.

Milford itself, one of the largest modern American towns, would be lost next to even a city like Brazzaville.

Yes, African science and technology are certainly now the most advanced on the planet, and some day perhaps we will build a civilization that can truly claim to be the highest the world has yet seen, but we only delude ourselves when we imagine that we have such a civilization now.

As of the middle of the twenty-second century, Space-Age America still stands as the pinnacle of man’s fight to master his environment.

Twentieth-century American man had a level of scientific knowledge and technological sophistication that we may not fully attain for another century.

What a pity he had so little deep understanding of his relationship to his environment or of himself.

The ramp linked up with the plane’s airlock, and after a minimal amount of confusion we debarked directly into a customs control office, which consisted of a drab, dun-colored, medium-sized room divided by a line of twelve booths across its width.

The customs officers in the booths were very polite, hardly glanced at our passports, and managed to process nearly a hundred passengers in less than ten minutes.

The American government was apparently justly famous for doing all it could to smooth the way for African tourists.

Beyond the customs control office was a small auditorium in which we were speedily seated by courteous uniformed customs agents.

A pale, sallow, well-built young lady in a trim blue customs uniform entered the room after us and walked rapidly through the center aisle and up onto the little low stage.

She was wearing, face-fitting atmosphere goggles, even though the terminal had a full seal.

She began to recite a little speech; I believe its actual wording is written into the American tourist-control laws.

“Good afternoon, ladies and gentlemen, and welcome to the United States of America.

We hope you’ll enjoy your stay in our country, and we’d like to take just a few moments of your time to give you some reminders that will help make your visit a safe and pleasurable one.

” She put her hand to her nose and extracted two small transparent cylinders filled with gray gossamer.

“These are government-approved atmosphere filters,” she said, displaying them for us.

“You will be given complimentary sets as you leave this room.

You are advised to buy only filters with the official United States Government Seal of Approval.

Change your filters regularly each morning, and your stay here should in no way impair your health.

However, it is understood that all visitors to the United States travel at their own risk.

You are advised not to remove your filters, except inside buildings or conveyances displaying a green circle containing the words FULL ATMOSPHERE SEAL.”

She took off her goggles, revealing a light red mask of welted skin that their seal had made around her eyes.

“These are self-sealing atmosphere goggles,” she said.

“If you have not yet purchased a pair, you may do so in the main lobby.

You are advised to secure goggles before leaving this terminal and to wear them whenever you venture out into the open atmosphere.

Purchase only goggles bearing the Government Seal of Approval, and always take care that the seal is air-tight.

“If you use your filters and goggles properly, your stay in the United States should be a safe and pleasant one.

The government and people of the United States wish you a good day, and we welcome you to our country.” We were then handed our filters and guided to the baggage area, where our luggage was already unloaded End waiting for us.

A sealed bus from the Milford International Inn was already waiting for those of us who had booked rooms there, and porters loaded the luggage on the bus while a representative from the hotel handed out complimentary atmosphere goggles.

The Americans were most efficient and most courteous; there was something almost unpleasant about the way we moved so smoothly from the plane to seats on a bus headed through the almost empty streets of Milford toward the faded white plastic block that was the Milford International Inn, by far the largest building in a town that seemed to be mostly small houses, much like an African residential village.

Perhaps what disturbed me was the knowledge that Americans were so good at this sort of thing strictly out of necessity.

Thirty percent of the total American Gross National Product comes from the tourist industry.

I keep telling my wife I gotta get out of this tourist business.

In the good old days, our ancestors would’ve given these African brothers nothing but about eight feet of rope.

They’d’ve shot off a nuclear missile and blasted all those black brothers to atoms! If the damned brothers didn’t have so much loose money, I’d be for riding every one of them back to Africa on a rail, just like the Space-Agers did with their black brothers before the Panic.

And I bet we could do it, too.

I hear there’s all kinds of Space-Age weapons sitting around in the ruins out West.

If we could only get ourselves together and dig them out, we’d show those Africans whose ancestors went to the moon while they were still eating each other.

But, instead, I found myself waiting with my copter bright and early at the International Inn for the next load of customers of Little Old New York Tours, as usual.

And I’ve got to admit that I’m doing pretty well off of it.

Ten years ago, I just barely had the dollars to make a down-payment on a used ten-seat helicopter, and now the thing is all paid off, and I’m shoveling dollars into my stash on every day-tour.

If the copter holds up another ten years, and this is a genuine Space-Age American Air Force helicopter restored and converted to energy cells in Aspen, not a cheap piece of African junk, I’ll be able to take my bundle and split to South America, just like a tycoon out of the good old days.

They say they’ve got places in South America where there’s nothing but wild country as far as you can see.

Imagine that! And you can buy this land.

You can buy jungle filled with animals and birds.

You can buy rivers full of fish.

You can buy air that doesn’t choke your lungs and give you cancer and taste like fried turds even through a brand-new set of filters.

Yeah, that’s why I suck up to Africans! That’s worth spending four or five hours a day in that New York hole, even worth looking at subway dwellers.

Every full day-tour I take in there is maybe twenty thousand dollars net toward South America.

You can buy ten acres of prime Amazon swampland for only fifty-six million dollars.

I’ll still be young ten years from now, I’ll only be forty.

I take good care of myself, I change my filters every day just like they tell you to, and I don’t use nothing but Key West Supremes, no matter how much the damned things cost.

I’ll have at least ten good years left; why, I could even live to be fifty five! And I’m gonna spend at least ten of those fifty-five years someplace where I can walk around without filters shoved up my nose, where I don’t need goggles to keep my eyes from rotting, where I can finally die from something better than lung cancer.

I picture South America every time I feel the urge to tell off those brothers and get out of this business.

For ten years with Karen in that Amazon swampland, I can take their superior-civilization crap and eat it and smile back at ’em afterward.

With filters wadded up my nose and goggle seals bruising the tender skin under my eyes, I found myself walking through the blue haze of the open American atmosphere, away from the second-class twenty-second-century comforts of the International Inn, and toward the large and apparently ancient tour helicopter.

As I walked along with the other tourists, I wondered just what it was that had drawn me here.

Of course, Space-Age America is my specialty, and I had reached the point where my academic career virtually required a visit to America, but, aside from that, I felt a personal motivation that I could not quite grasp.

No doubt, I know more about Space-Age America than all but a handful of modern Americans, but the reality of Space-Age civilization seems illusive to me.

I am an enlightened modern African, five generations removed from the bush; yet I have seen films, the obscure ghost to woof Las Vegas sitting in the middle of a terrible desert clogged with vast mechanized temples to the God of Chance; Mount Rushmore, where the Americans carved an entire landscape into the likenesses of their national heroes; the Cape Kennedy National Shrine, where rockets of incredible size are preserved almost intact, which have made me feel like an ignorant primitive trying to understand the minds of gods.

One cannot contemplate the Space Age without concluding that the Space-Agers possessed a kind of sophistication which we modern men have lost.

Yet they destroyed themselves.

Yes, perhaps the resolution of this paradox was what I hoped to find here, aside from academic merit.

Certainly, true understanding of the Space-Age mind cannot be gained from study of artifacts and records, if it could, I would have it.

A true scholar, it has always seemed to me, must seek to understand, not merely to accumulate knowledge.

No doubt, it was understanding that I sought here.

Up close, the Little Old New York Tours helicopter was truly impressive, an antique ten-seater built during the Space-Age for the military by the look of it, and lovingly restored.

But the American atmosphere had still been breathable even in the cities when it was built, so I was certain that this copter had only a filter system of questionable quality, no doubt installed by the contemporary natives in modern times.

I did not want anything as flimsy as all that between my eyes and lungs and the American atmosphere, so I ignored the FULL ATMOSPHERE SEAL sign and kept my filters in and my goggles on as I boarded.

I noticed that the other tourists were doing the same.

Mike Ryan, the native guide and pilot, had been recommended to me by a colleague from the University of Nairobi.

A professor’s funds are quite limited, of course, especially one who has not attained significant academic stature as yet, and the air fares ate into my already meager budget to the point where all I could afford was three days in Milford, four in Aspen, three in Needles, five in Eureka, and a final three at Cape Kennedy on the way home.

Aside from the Cape Kennedy National Shrine, none of these modern American towns actually contained Space-Age ruins of significance.

Since it is virtually impossible, and, at any rate, prohibitively dangerous, to visit major Space-Age ruins without a helicopter and a native guide, and since a private copter and guide would be far beyond my means, my only alternative was to take a day-tour like everyone else.

My Kenyan friend had told me that Ryan was the best guide to Old New York that he had had in his three visits.

Unlike most of the other guides, he actually took his tours into a subway station to see live subway dwellers.

There are reportedly only a thousand or two subway dwellers left; they are nearing extinction.

It seemed like an opportunity I should not miss.

At any rate, Ryan’s charge was only about five hundred dollars above the average guide’s.

Ryan stood outside the helicopter in goggles, helping us aboard.

His appearance gave me something of a surprise.

My Kenyan informant had told me that Ryan had been in the tour business for ten years; most guides who had been around that long were in terrible shape.

No filters could entirely protect a man from that kind of prolonged exposure to saturation smog; by the time they’re thirty, most guides already have chronic emphysema, and their lung-cancer rate at age thirty-five is over fifty percent.

But Ryan, who could not be under thirty, had the general appearance of a forty-year-old Boer; physiologically, he should have looked a good deal older.

Instead, he was short, squat, had only slightly graying black hair, and looked quite alert, even powerful.

But, of course, he had the typical American grayish-white pimply pallor.

There were eight other people taking the tour, a full copter.

A prosperous-looking Kenyan who quickly introduced himself as Roger Koyinka, traveling with his wife; a rather strange-looking Ghanaian in very rich-looking old-fashioned robes and his similarly clad wife and young son; two rather willowy and modishly dressed young men who appeared to be Luthuliville dandies, and the only other person in the tour who was traveling alone, an intense young man whose great bush of hair, stylized dashiki, and gold earring proclaimed that he was an Amero-African.

I drew a seat next to the Amero-African, who identified himself as Michael Lumumba rather diffidently when I introduced myself.

Ryan gave us a few moments to get acquainted, I learned that the Ghanaian was named Kulongo, that Koyinka was a department store executive from Nairobi, that the two young men were named Ojubu and Ruala, while he checked out the helicopter, and then seated himself in the pilot’s seat, back toward us, goggles still in place, and addressed us without looking back through an internal public address system.

“Hello, ladies and gentlemen, and welcome to your Little Old New York Tour.

I’m Mike Ryan, your guide to the wonders of Old New York, Space-Age America’s greatest city.

Today you’re going to see such sights as the Fuller Dome, the Empire State Building, Rockefeller Center, and, as a grand finale, a subway station still inhabited by the direct descendants of the Space-Age inhabitants of the city.

So don’t just think of this as a guided tour, ladies and gentlemen.

You are about to take part in the experience of a lifetime, an exploration of the ruins of the greatest city built by the greatest civilization ever to stand on the face of the earth.”

“Stupid arrogant honkie!” the young man beside me snarled aloud.

There was a terrible moment of shocked, shamed embarrassment in the cabin, as all of us squirmed in our seats.

Of course, the Amero-Africans are famous for this sort of tastelessness, but to be actually confronted with this sort of blatant racism made one for a moment ashamed to be black.

Ryan swiveled very slowly in his seat.

His face displayed the characteristic red flush of the angered Caucasian, but his voice was strangely cold, almost polite: “You’re in the United States now, Mister Lumumba, not in Africa.

I’d watch what I said if I were you.

If you don’t like me or my country, you can have your lousy money back.

There’s a plane leaving for Conakry in the morning.”

“You’re not getting off that easy, honkie,” Lumumba said.

“I paid my money, and you’re not getting me off this helicopter.

You try, and I go straight to the tourist board, and there goes your licence. ”

Ryan stared at Lumumba for a moment.

Then the flush began to fade from his face, and be turned his back on us again, muttering, “Suit yourself, pal. I promise you an interesting ride.”

A muscle twitched in Lumumba’s temple; he seemed about to speak again.

“Look here, Mister Lumumba,” I whispered at him sharply, “we’re guests in this country, and you’re making us look like boorish louts in front of the natives.

If you have no respect for your own dignity, have some respect for ours.”

“You stick to your pleasures, and I’ll stick to mine,” he told me, speaking more calmly, but obviously savoring his own bitterness.

“I’m here for the pleasure of seeing the descendants of the stinking honkies who kicked my ancestors out grovel in the putrid mess they made for themselves.

And I intend to get my money’s worth.”

I started to reply, but then restrained myself.

I would have to remain on civil terms with this horrid young man for hours.

I don’t think I’ll ever understand these Amero-Africans and their pointless blood-feud.

I doubt if I want to.

I started the engines, lifted her off the pad, and headed east into the smog bank trying hard not to think of that black brother Lumumba.

No wonder so many of his ancestors were lynched by the Space-Agers! Sometime during the next few hours, that crud was going to get his.

Through by cabin monitor (this Air Force Iron was just loaded with real Space-Age stuff) I watched the stupid looks on their flat faces as we headed for what looked like a solid wall of smoke at about one hundred miles per hour.

From the fringes, a major smog bank looks like that, solid as a steel slab, but once you’re inside there’s nothing but a blue haze that anyone with a halfway decent set of goggles can see right through.

“We are now entering the East Coast smog bank, ladies and gentlemen,” I told them.

“This smog bank extends roughly from Bangor, Maine, in the north to Jacksonville, Florida in the south, and from the Atlantic coastline in the east to the slopes of the Alleghenies in the west. It is the third largest smog bank in the United States.”

Getting used to the way things look inside the smog always holds ’em for a while.

Inside a smog bank, the color of everything is kind of washed-out, grayed, and blued.

The air is something you can see, a mist that doesn’t move; it almost sparkles at you.

For some reason, these Africans always seem to be knocked out by it.

Imagine thinking stuff like that is beautiful, crap that would kill you horribly and slowly in a couple of days if you were stupid or unlucky enough to breathe it without filters.

Yeah, they sure were a bunch of brothers! Some executive from Nairobi who acted like just being in the same copter with an American might give him and his wife lung cancer.

Two rich young fruits from Luthuliville who seemed to be traveling together so they could congratulate themselves on how smart they both were for picking such rich parents.

Some professor named Balewa who had never been to the States before, but probably was sure he knew what it was all about.

A backwoods jungle-bunny named Kulongo who had struck it rich off uranium or something, taking his wife and kid on the grand tour.

And, of course, that creep, Lumumba.

The usual load of African tourists.

Man, in the good old days, these niggers wouldn’t have been good enough to shine our shoes! Now we were flying over the old state of New Jersey.

The Space-Agers did things in New Jersey that not even the African professors have figured out.

It was weird country we were crossing: endless patterns of box-houses, all of them the same, all bleached blue-gray by two centuries of smog; big old freeways jammed with the wreckage of cars from the Panic of the Century; a few twisted gray trees and a patch of dry grass here and there that somehow managed to survive in the smog.

And this was western Jersey; this was nothing.

Further east, it was like an alien planet or something.

The view from the Jersey Turnpike was a sure tourist-pleaser.

It really told them just where they were.

It let them know that the Space-Agers could do things they couldn’t hope to do.

Or want to.

Yeah, the Jersey lowlands are spectacular, all right, but why in hell, did our ancestors want to do a thing like that? It really makes you think.

You look at the Jersey lowlands and you know that the Space-Agers could do about anything they wanted to.

But why in hell did they want to do some of the things they did? There was something about actually standing in the open American atmosphere that seemed to act directly on the consciousness, like kit.

Perhaps it was the visual effect.

Ryan had landed the helicopter on a shattered arch of six-lane freeway that soared like the frozen contrail of an ascending jet over a surreal metallic jungle of amorphous Space-Age rubble on a giant’s scale, all crumbling rusted storage tanks, ruined factories, fantastic mazes of decayed valving and piping, filling the world from horizon to horizon.

As we stepped out onto the cracked and pitted concrete, the spectrum of reality changed, as if we were suddenly on the surface of a planet circling a bluer and grayer sun.

The entire grotesque panorama appeared as if through a blue-gray filter.

But we were inside the filter; the filter was the open American smog and it shone in drab sparkles all around us.

Strangest of all, the air seemed to remain completely transparent while possessing tangible visible substance.

Yes, the visual effects of the American atmosphere alone are enough to affect you like some hallucinogenic drug: distorting your consciousness by warping your visual perception of your environment.

Of course, the exact biochemical effects of breathing saturation smog through filters are still unknown.

We know that the American atmosphere is loaded with hydrocarbons and nitrous oxides that would kill a man in a matter of days if he breathed them directly.

We know that the atmosphere filters developed toward the end by the Space-Agers enable a man to breathe the American atmosphere for up to three months without permanent damage to his health and enable the modern Americans, who have to breathe variations of this filtered poison every moment of their lives, to often live to be fifty.

We know how to duplicate the Space-Age atmosphere filters, and we more or less know how their complex catalytic fibers work, but the reactions that the filters must put the American atmosphere through to make it breathable are so complex that the only thing we can say for sure of what comes out the other side is that it usually takes about four decades to kill you.

Perhaps that strange feeling that came over me was a combination of both effects.

But, for whatever reasons, I saw that weird landscape as if in a dream or a state of intoxication: everything faded and misty and somehow unreal, vaguely supernatural.

Beside me, staring silently and with a strange dignity at the totally artificial vista of monstrous rusted ruins, stood the Ghanaian, Kulongo.

When he finally spoke, his wife and son seemed to hang on his words, as if he were one of the old chiefs dispensing tribal wisdom.

“I have never seen such a place as this,” Kulongo said.

“In this place, there once lived a race of demons or witchdoctors or gods.

There are those who would call me an ignorant savage for saying this thing, but only a fool doubts what he sees with his eyes or his heart.

The men who made these things were not human beings like us.

Their souls were not as our souls.”

Although he was putting it in naive and primitive terms, there was the weight of essential truth in Kulongo’s words.

The broken arch of freeway on which we stood reared like the head of a snake whose body was a six-lane road clogged with the rusted corpses of what had been a region wide traffic-jam during the Panic of the Century.

The freeway led south, off into the fuzzy horizon of the smog bank, through a ruined landscape in which nothing could be seen that was not the decayed work of man; that was not metal or concrete or asphalt or plastic or Space-Age synthetic.

It was like being perched above some vast rained machine the size of a city, a city never meant for man.

The scale of the machinery and the way it encompassed the visual universe made it very clear to me that the reality of America was something that no one could put into a book or a film.

I was in America with a vengeance.

I was overwhelmed by the totality with, which the Space-Agers had transformed their environment, and by the essential incomprehensibility, despite our sophisticated sociological and psycho-historical explanations, of why they had done such a thing and of how they themselves had seen it.

“Their souls were not as our souls” was as good a way to put it as any.

“Well, it’s certainly spectacular enough,” Ruala said to his friend, the rapt look on his face making a mockery of his sarcastic tone.

“So it is,” Ojubu said softly.

Then, more harshly: “It’s probably the largest junk heap in the world.”

The two of them made a halfhearted attempt at laughter, which withered almost immediately under the contemptuous look that the Kulongos gave them; the timeless look that the people of the bush have given the people of the towns for centuries, the look that said only cowardly fools attempt to hide their fears behind a false curtain of contempt, that only those who truly fear magic need to openly mock it.

And again, in their naive way, the Kulongos were right.

Ojubu and Ruala were just a shade too shrill, and, even while they played at diffidence, their eyes remained fixed on that totally surreal metal landscape.

One would have to be a lot worse than a mere fool not to feel the essential strangeness of that place.

Even Lumumba, standing a few yards from the rest of us, could not tear his eyes away.

Just behind us, Ryan stood leaning against the helicopter.

There was a strange power, perhaps a sarcasm as well, in his words as he delivered what surely must have been his routine guide’s speech about this place.

“Ladies and gentlemen, we are now standing on the New Jersey Turnpike, one of the great highways that linked some of the mighty cities of Space-Age America.

Below you are the Jersey lowlands, which served as a great manufacturing, storage, power-producing, and petroleum refining and distribution center for the greatest and largest of the Space-Age cities, Old New York.

As you look across these incredible ruins, larger than most modern African cities, think of this: all of this was nothing to the Space-Age Americans but a minor industrial area to be driven through at a hundred miles an hour without even noticing.

You’re not looking at one of the famous wonders of Old New York, but merely at an unimportant fringe of the greatest city ever built by man.

Ladies and gentlemen, you’re looking at a very minor work of Space-Age man!”

“Crazy damned honkies.” Lumumba muttered.

But there was little vehemence or real meaning in his voice, and, like the rest of us, he could not tear his eyes away.

It was not hard to understand what was going through his mind.

Here was a man raised in the Amero-African enclaves on an irrational mixture of hate for the fallen Space-Agers, contempt for their vanished culture, fear of their former power, and perhaps a kind of twisted blend of envy and identification that only an Amero-African could fully understand.

He had come to revel in the sight of the ruins of the civilization that had banished his ancestors, and now he was confronted with the inescapable reality that the “honkies” whose memory he both hated and feared had indeed possessed power and knowledge not only beyond his comprehension, but applied to ends which his mind was not equipped to understand.

It must have been a humbling moment for Michael Lumumba.

He had come to sneer and had been forced instead to gape.

I tore my gaze away from that awesome vista to look at Ryan; there was a grim smile on his pale, unhealthy face as he drank in our reactions.

Clearly, he had meant this sight to humble us, and, just as clearly, it had.

Ryan stared back at me through his goggles as he noticed me watching him.

I couldn’t read the expression in his watery eyes through the distortion of the goggle lenses.

All I understood was that somehow some subtle change had occurred in the pattern of the group’s interrelationships.

No longer was Ryan merely a native guide, a functionary, a man without dignity.

He had proved that he could show us sights beyond the limits of the modern world.

He had reminded us of just where we were, and who and what his ancestors had been.

He had suddenly gained secondhand stature from the incredible ruins around him, because, in a very real way, they were his ruins.

Certainly they were not ours.

“I’ve got to admit they were great engineers,” Koyinka, the Kenyan executive, said.

“So were the ancient Egyptians,” Lumumba said, recovering some of his bitterness.

“And what did it get them? A fancy collection of old junk over their graves, exactly what it got these honkies.”

“If you keep it up, pal,” Ryan said coldly, “you may get a chance to see something that’ll impress you a bit more than these ruins.”

“Is that a threat or a promise, Ryan?”

“Depends on whether you’re a man, or a boy, Mister Lumumba.” Lumumba had nothing to say to that, whatever it all had meant.

Ryan appeared to have won a round in some contest between them.

And when we followed Ryan back into the helicopter, I think we were all aware that for the next few hours, this pale, unhealthy American would be something more than a mere convenient functionary.

We were the tourists; he was the guide.

But as we looked over our shoulders at the vast and overwhelming heritage that had been created and then squandered by his ancestors, the relationship that those words described took on a new meaning.

The ancestral ruins off which he lived, were a greater thing in some absolute sense than the totality of our entire living civilization.

He had convinced us of that, and he knew it.

That view across the Jersey lowlands always seems to shut them up for a while.

Even that crud, Lumumba.

God knows why.

Sure it’s spectacular, bigger than anything these Africans could ever have seen where they come from, but when you come right down to it, you gotta admit that Ojubu was right, the Jersey lowlands are nothing but a giant pile of junk.

Crap.

Space-Age garbage.

Sometimes looking at a place like that can piss me off.

I mean, we had some ancestors.

They built the greatest civilization the world ever saw, but what did they leave for us?

The most spectacular junk piles in the world, air that does you in sooner or later even through filters, and a continent where seeing something alive that people didn’t put there is a big deal.

Our ancestors went to the moon, they were a great people, the greatest in history, but sometimes I get the feeling they were maybe just a little out of their minds.

Like that crazy “Merge with the Cosmic All” thing I found that time in Grand Central, still working after two centuries or so; it must do something besides kill people, but what? I dunno, maybe our ancestors went a little over the edge, sometimes.

Not that I’d ever admit a thing like that to any black brothers! The Space-Agers may have been a little bit nuts, but who are these Africans to say so, who are they to decide whether a civilization that had them beat up and down the line was sane or not? Sane according to whom? Them, or the Space-Agers? For that matter, who am I to think a thing like that?

An ant or a rat living off their garbage.

Who are nobodies like us and the Africans to judge people who could go to the moon? Like I keep telling Karen, this damned tourist business is getting to me.

I’m around these Africans too much.

Sometimes, if I don’t watch myself, I catch myself thinking like them.

Maybe it’s the lousy smog this far into the smog bank, but hell, that’s another crazy African idea! That’s what being around these Africans does to me, and looking at subway dwellers five times a week sure doesn’t help, either.

Let’s face it, stuff like the subways and the lowlands is really depressing.

It tells a man he’s a nothing.

Worse, it tells him that people who were better than he is still managed to screw things up.

It’s just not good for your mind.

But as the copter crested the lip of the Palisades ridge and we looked out across that wide Hudson River at Manhattan, I was reminded again that this crummy job had its compensations.

If you haven’t seen Manhattan from a copter crossing the Hudson from the Jersey side, you haven’t seen nothing, pal.

That Fuller Dome socks you right in the eye.

It’s ten miles in diameter.

It has facets that make it glitter like a giant blue diamond floating over the middle of the island.

Yeah, that’s right, it floats.

It’s made of some Space-Age plastic that’s been turned blue and hazy by a couple of centuries of smog, it’s ten miles wide at the base, and the goddamned thing floats over the middle of Manhattan a few hundred feet off the ground at its rim like a cloud or a hover or something.

No motors, no nothing.

It’s just a hemisphere made of plastic panels and alloy tubing and it floats over the middle of Manhattan like half a giant diamond all by itself.

Now, that’s what I call a real piece of Space-Age hardware! I could hear them suck in their breath behind me.

Yeah, it really does it to you.

I almost forgot to give them the spiel.

I mean, who wants to? What can you really say to someone while he’s looking at the Fuller Dome for the first time?

“Ladies and gentlemen, you are now looking at the world-famous Fuller Dome, the largest architectural structure ever built by the human race. It is ten miles in diameter.

It encloses the center of Manhattan Island, the heart of Old New York.

It has no motors, no power source, and no moving parts.

But it floats in the air like a cloud.

It is considered the First Wonder of the World.”

What else is there to say? We came in low across the river toward that incredible floating blue diamond, the Fuller Dome, parallel to the ruins of a great suspension bridge which had collapsed and now hung in fantastic rusted tatters half in and half out of the water.

Aside from Ryan’s short guidebook speech, no one said a word as we crossed the water to Manhattan.

Like the moon landing, the Fuller Dome was one of the peak achievements of the Space Age, a feat beyond the power of modern African civilization.

As I understood it, the Dome held itself aloft by convection currents created by its own greenhouse effect, though this has always seemed to me the logical equivalent of a man lifting himself by his own shoulders.

No one quite knows exactly how a dome this size was built, but the records show that it required a fleet of two hundred helicopters.

It took six weeks to complete.

It was named after Buckminster Fuller, one of the architectural geniuses of the early Space Age, but it was not built till after his death, though it is considered his monument.

But it was more than that; it was staggeringly, overwhelmingly beautiful.

We crossed the river and headed toward the rim of the Fuller Dome at about two hundred feet, over a shoreline of crumbling docks and the half-sunken hulks of rusted-out ships; then over a wide strip of elevated highway filled with the usual wrecked cars; and finally we slipped under the rim of the Dome itself, an incredibly thin metal hoop floating in the air from which the Dome seemed to blossom like a soap bubble from a child’s bubble pipe.

And we were flying inside the Fuller Dome.

It was an incredible sensation, the world inside the Dome existed in blue crystal.

Our helicopter seemed like a buzzing fly that had intruded into an enormous room.

The room was a mile high and ten miles wide.

The facets of the Fuller Dome had been designed to admit natural sunlight and thus preserve the sense of being outdoors, but they had been weathered to a bluish hue by the saturation smog.

As a result, the interior of the Dome was a room on a superhuman scale, a room filled with a pale blue light, and a room containing a major portion of a giant city.

Towering before us were the famous skyscrapers of Old New York, a forest of rectangular monoliths hundreds of feet high, in some cases well over a thousand feet tall.

Some of them stood almost intact, empty concrete boxes transformed into giant somber tombstones by the eerie blue light that permeated everything.

Others had been ripped apart by explosions and were jagged piles of girders and concrete.

Some had bad walls almost entirely of glass; most of these were now airy mazes of framework and concrete platforms, where the blue light here and there flashed off intact patches of glass.

And far above the tops of the tallest buildings was the blue stained-glass faceted sky of the Fuller Dome.

Ryan took the helicopter up to the five-hundred-foot level and headed for the giant necropolis, a city of monuments built on a scale that would have caused the pharaohs to whimper, packed casually together like family houses in an African residential village.

And all of it was bathed in a sparkly blue-gray light which seemed to enclose a universe, here in the very core of the East Coast smog bank, where everything seemed to twinkle and shimmer.

We all gasped as Ryan headed at one hundred miles per hour for a thin canyon that was the gap between two rows of buildings which faced each other across a not-very-wide street hundreds of feet below.

For a moment, we seemed to be a stone dropping toward a narrow shaft between two immense cliffs—then, suddenly, the copter’s engines screamed, and the copter seemed to somehow skid and slide through the air to a dead hover no more than a hundred feet from the sheer face of a huge gray skyscraper.

Ryan’s laugh sounded unreal, partially drowned out by the descending whine of the copter’s relaxing engines.

“Don’t worry, folks,” he said over the public address system, “I’m in control of this aircraft at all times.

I just thought I’d give you a little thrill.

Kind of wake up those of you who might be sleeping, because you wouldn’t want to’ miss what comes next: a helicopter tour of what the Space-Agers called ‘The Sidewalks of New York.’ ” And we inched forward at the pace of a running man; we seemed to drift into a canyon between two parallel lines of huge buildings that went on for miles.

Man, no matter how many times I come here, I still feel weird inside the Fuller Dome.

It’s another world in there.

New York seems like it’s built for people fifty feet tall; it makes you feel so small, like you’re inside a giant’s room.

But when you look up at the inside of the Dome, the buildings that seemed so big seem so small; you can’t get a grasp on the scale of anything.

And everything is all blue.

And the smog is so heavy you think you could eat it with a fork.

And you know that the whole thing is completely dead.

Nothing lives in New York between the Fuller Dome and the subways, where several thousand subway dwellers stew in their own muck.

Nothing can.

The air inside the Fuller Dome is some of the worst in the country, almost as bad as that stuff they say you can barely see through that fills the Los Angeles basin.

The Space-Agers didn’t put up the Dome to atmosphere-seal a piece of the city; they did it to make the city warmer and keep the snow off the ground.

The smog was still breathable then.

So the inside of the Dome is open to the naked atmosphere, and it actually seems to suck in the worst of the smog, maybe because it’s about twenty degrees hotter inside the Dome than it is outside; something about convection currents, the Africans say, but I dunno.

It’s creepy, that’s what it is.

Flying slowly between two lines of skyscrapers, I had the feeling I was tiptoeing very carefully around some giant graveyard in the middle of the night.

Not any of that crap about ghosts that I’ll bet some of these Africans still believe deep down; this whole city really was a graveyard.

During the Space Age, millions of people lived in New York; now there was nothing alive here but a couple thousand stinking subway dwellers slowly strangling themselves in their stinking sealed subways.

So I kind of drifted the copter in among the skyscrapers for a while, at about a hundred feet, real slow, almost on hover, and just let the customers suck in the feel of the place, keeping my mouth shut.

After a while, we came to a really wide street, jammed to overflowing with wrecked and rusted cars that even filled the sidewalks, as if the Space-Agers had built one of their crazy car pyramids right here in the middle of Manhattan, and it had just sort of run like hot wax.

I hovered the copter over it for a while.

“Folks,” I told the customers, “below you, you see some of the wreckage from the Panic of the Century which fills the sidewalks of New York.

The Panic of the Century started right here in New York.

Imagine, ladies and gentlemen, at the height of the Space Age, there were more than one hundred million cars, trucks, buses, and other motor vehicles operating on the freeways and streets of the United States.

A car for every two adults! Look below you and try to imagine the magnificence of the sight of all of them on the road all at once!” Yeah, that would’ve been something to see, all right! From a helicopter, that is.

Man, those Space-Age is sure had guts, driving around down there jammed together on the freeways at copter speeds with only a few feet between them.

They must’ve had fantastic reflexes to be able to handle it.

Not for me, pal, I couldn’t do it, and I wouldn’t want to.

But, God, what this place must’ve been like, all lit up at night in bright colored lights, millions of people tearing around in their cars all at once! Hell, what’s the population of the United States today, thirty, forty million, not a city with five hundred thousand people, and nothing in all the world on the scale of this.

Damn it, those were the days for a man to have lived! Now look at it! The power all gone except for whatever keeps the subway electricity going, so the only light above ground is that blue stuff that makes everything seem so still and quiet and weird, like the city’s embalmed or something.

The buildings are all empty crumbling wrecks, burned out, smashed up by explosions, and the cars are all rusted garbage, and the people are dead, dead, dead.

It’s enough to make you cry, if you let it get to you.

We drifted among the ruins of Old New York like some secretive night insect.

By now it was afternoon, and the canyons formed by the skyscrapers were filled with deep purple shadows and intermittent avenues of pale blue light.

The world under the Fuller Dome was composed of relative darknesses of blue, much as the world under the canopy of a heavy rain forest is a world of varying greens.

We dipped low and drifted for a few moments over a large square where the top of a low building had been removed by an explosion to reveal a series of huge cuts and canyons extending deep into the bowels of the earth, perhaps some kind of underground train terminal, perhaps even a ruined part of the famous New York subways.

“This is a burial ground of magics,” Kulongo said.

“The air is very heavy here.”

“They sure knew how to build,” Koyinka said.

Beside me, Michael Lumumba seemed subdued, perhaps even nervous.

“You know, I never knew it was all so big,” he muttered to me.

“So big, and so strange, and so, so.”

“Space Age, Mister Lumumba?” Ryan suggested over the intercom.

Lumumba’s jaw twitched.

He was obviously furious at having Ryan supply the precise words he was looking for.

“Inhuman, honkie, inhuman was what I was going to say,” he lied transparently.

“Wasn’t there an ancient saying, ‘New York is a nice place to visit, but I wouldn’t want to live there?’ ” “Never heard that one, pal,” Ryan said.

“But I can see how your ancestors might’ve felt that way.

New York was always too much for anyone but a real Space-Ager.”

There was considerable truth in what they both said, though of course neither was interested in true insight.

Here in the blue crystal world under the Fuller Dome, in a helicopter buzzing about noisily in the graveyard silence, reduced by the scale of the buildings to the relative size of an insect, I felt the immensity of what had been Space-Age America all around me.

I felt as if I were trespassing in the mansions of my betters.

I felt like a bug, an insect.

I remembered from history, not from instinct, how totally America had dominated the world during the Space Age, not by armed conquest, but by the sheer overwhelming weight of its very existence.

I had never before been quite able to grasp that concept.

I understood it perfectly now.

I gave them the standard helicopter tour of the sidewalks of New York.

We floated up Broadway, the street that had been called The Great White Way, at about fifty feet, past crazy rotten networks of light steel girders, crumbled signs, and wiring on a monstrous scale.

At a thousand feet, we circled the Empire State Building, one of the oldest of the great skyscrapers, and now one of (ho best-preserved, a thousand-foot slab of solid concrete, probably just the kind of tombstone the Space-Agers would’ve put up for themselves if they had thought about it.

Yeah, I gave them all the usual stuff.

The ruins of Rockefeller Center.

The U N Plaza Crater.

Of course, they were all sucking it up, even Lumumba, though of course the slime wouldn’t admit it.

After this, they’d be ripe for a nasty peek at the subway dwellers, and after they got through gaping at the animals, they’d be ready for dinner back in Milford, feeling they had got their money’s worth.

Yeah, I can get the same money for a five-hour tour that most guides get for six, because I’ve got the stomach to take them into a subway station.

As usual, it had just the right effect when I told them we were going to end the tour with a visit on foot to an inhabited subway station.

Instead of bitching and moaning that the tour was too short, that they weren’t getting their money’s worth, they were all eager, and maybe a little scared, at actually walking among the really primitive natives.

Once they’d had their fill of the subway dwellers, a ride home across the Hudson into the sunset would be enough to convince them they’d had a great day.

So we were going to see the subway dwellers! Most of the native guides avoided the subways, and the American government for some reason seemed to discourage research by foreigners.

A subtle discouragement, perhaps, but discouragement nevertheless.

In a paper he published a few years ago, Omgazi had theorized that the modern Americans in the vicinity of New York had a loathing of the subway dwellers that amounted to virtually a superstitious dread.

According to him, the subway dwellers, because they were direct descendants of diehard Space-Agers who had atmosphere-sealed the subways and set up a closed ecology inside rather than abandon New York, were identified with their ancestors in the minds of the modern Americans.

Hence, the modern Americans shunned the subway dwellers because they considered them shamans on a deep subconscious level.

It had always seemed to me that Omgazi was being rather ethnocentric.

He was dealing, after all, with modern Americans, not nineteenth-century Africans.

Now I would have a chance to observe some subway dwellers myself.

The prospect was most exciting.

For, although the subway dwellers were apparently degenerating toward extinction at a rapid rate, in one respect they were unique in all the world—they still lived in an artificial environment that had been constructed during the Space Age.

True, it had been a hurried, makeshift environment in the first place, and it and its inhabitants had deteriorated tremendously in two centuries, but, whatever else they were or weren’t, the subway dwellers were the only enclave of Space-Age Americans left on the face of the earth.

If it were possible at all for a modern African to truly come to understand the reality of Space-Age America, surely confrontation with the lineal descendants of the Space Age would provide the key.

Ryan set the helicopter down in what seemed to be some kind of large open terrace behind a massive, low, concrete building.

The terrace was a patchwork of cracked concrete walkways and expanses of bare gray earth.

Once, apparently, it had been a small park, before the smog had become lethal to vegetation.

As a denuded ruin in the pale blue light, it seemed like some strange cold corpse as the helicopter kicked up dry clouds of dust from the surface of the dead parkland.

As I stepped out with the others into the blue world of the Fuller Dome, I gasped: I had a momentary impression that I had stepped back to Africa, to Accra or Brazzaville.

The air was rich and warm and humid on my skin.

An instant later, the visual effect, everything a cool pale blue, jarred me with its arctic-vista contrast.

Then I noticed the air itself and I shuddered, and was suddenly hyperconscious of the filters up my nostrils and the goggles over my eyes, for here the air was so heavy With smog that it seemed to sparkle electrically in the crazy blue light.

What incredible, beautiful, foul poison! Except for Ryan, all of us were clearly overcome, each in his own way.

Kulongo blinked and stared solemnly for a moment like a great bear; his wife and son seemed to lean into the security of his calm aura.

Koyinka seemed to fear that he might strangle; his wife twittered about excitedly, tugging at his hand.

The two young men from Luthuliville seemed to be self-consciously making an effort to avoid clutching at each other.

Michael Lumumba mumbled something unintelligible under his breath.

“What was that you said, Mister Lumumba?”

Ryan said a shade gratingly as he led us out of the park down a crumbling set of stone-and-concrete stairs.

Something seemed to snap inside Lumumba; he broke stride for a moment, frozen by some inner event while Ryan led the rest of us onto a walkway between a line of huge silent buildings and a street choked with the rusted wreckage of ancient cars, timelessly locked in their death-agony in the sparkly blue light.

“What do you want from me, you damned honkie?” Lumumba shouted shrilly.

“Haven’t you done enough to us?” Ryan broke stride for a moment, smiled back at Lumumba rather cruelly, and said, “I don’t know what you’re talking about, pal.

I’ve got your money already.

What the hell else could I want from you?” He began to move off down the walkway again, threading his way past and over bits of wrecked cars, fallen masonry, and amorphous rubble.

Over his shoulder, he noticed that Lumumba was following along haltingly, staring up at the buildings, nibbling at his lower lip.

“What’s the matter, Lumumba?” Ryan shouted back at him.

“Aren’t these ruins good enough for you to gloat over? You wouldn’t be just a little bit afraid, would you?”

“Afraid? Why should I be afraid?” Ryan continued on for a few more meters; then he stopped and leaned up against the wall of one of the more badly damaged skyscrapers, near a jagged cavelike opening that led into the dark interior.

He looked directly at Lumumba.

“Don’t get me wrong, pal,” he said, “I wouldn’t blame you if you were a little scared of the subway dwellers. After all, they’re the direct descendants of the people that kicked your ancestors out of this country. Maybe you got a right to be nervous.”

“Don’t be an idiot, Ryan, Why should a civilized African be afraid of a pack of degenerate savages?” Koyinka said as we all caught up to Ryan.

Ryan shrugged.

“How should I know?” he said.

“Maybe you ought to ask Mister Lumumba.” And with that, he turned his back on us and stepped through the jagged opening into the ruined skyscraper.

Somewhat uneasily, we followed him into what proved to be a large antechamber that seemed to lead back into some even larger cavernous space that could be sensed rather than seen looming in the darkness.

But Ryan did not lead us toward this large, open space; instead, he stopped before he had gone more than a dozen steps and waited for us near a crumbling metal-pipe fence that guarded two edges of what looked like a deep pit.

One long edge of the pit was flush with the right wall of the antechamber; at the far short edge, a flight of stone stairs began which seemed to go all the way to the shadow-obscured bottom.

Ryan led us along the railing to the top of the stairs, and from this angle I could see that the pit had once been the entrance to the mouth of a large tunnel whose floor had been the floor of the pit at the foot of the stairs.

Now an immense and ancient solid slab of steel blocked the tunnel mouth and formed the fourth wall of the pit.

But in the center of this rusted steel slab was a relatively new airlock that seemed of modern design.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” Ryan said, “we’re standing by a sealed entrance to the subways of Old New York, During the Space Age, the subways were the major transportation system of the city and there were hundreds of entrances like this one.

Below the ground was a giant network of stations and tunnels through which the Space-Agers could go from any point in the city to any other point.

Many of the stations were huge and contained shops and restaurants.

Every station had automatic vending machines which sold food and drinks and a lot of other things, too.

Even during the Space Age, the subways were a kind of little world.”

He started down the stairs, still talking.

“During the Panic of the Century, some of the New Yorkers chose not to leave the city.

Instead, they retreated to the subways, sealed all the entrances, installed space-station life-support machinery, everything from a fusion reactor to hydroponics, and cut themselves off from the outside world.

Today, the subway dwellers, direct descendants of those Space-Agers, still inhabit several of the subway stations.

And most of the Space-Age life-support machinery is still running.

There are probably Space-Age artifacts down here that no modern man has ever seen.”

At the bottom of the pit, Ryan led us to the airlock and opened the outer door.

The airlock proved to be surprisingly large.

“This airlock was installed by the government about fifty years ago, soon after the subway dwellers were discovered,” he told us as he jammed us inside and began the cycle.

“It was part of a program to recivilize the subway dwellers.

The idea was to let scientists get inside without contaminating the subway atmosphere with smog.

Of course, the whole program was a flop.

Nobody’s ever going to get through to the subway dwellers, and there are less of ’em every year.

They don’t breed much, and in a generation or so they’ll be extinct.

So you’re all in for a really unique experience.

Not everyone will be able to tell their grandchildren that they actually saw a live subway dweller!” The inner airlock door opened into an ancient square cross- sectioned tunnel made of rotting gray concrete.

The air, even through filters, tasted horrible: very thin, somehow crisp without being at all bracing, with a chemical undertone, yet reeking with organic decay odors.

Breathing was very difficult; it felt like we were at the fifteen-thousand-foot level.

“I’m not telling you all this for my health,” Ryan said as he moved us out of the airlock.

“I’m telling it to you for your health: don’t mess with these people.

Look and don’t touch.

Listen, but keep your mouths shut.

They may seem harmless, they may be harmless, but no one can he sure.

That’s why not many guides will take people down here.

I hope you all have that straight. ”

The last remark had obviously been meant for Lumumba, but he didn’t seem to react to it; he seemed subdued, drawn up inside himself.

Perhaps Ryan was right, perhaps in some un-guessable way, Lumumba was afraid.

It’s impossible to really understand these Amero-Africans.

We moved off down the corridor.

The overhead lights, at least in this area, were clearly modern, probably installed when the airlock had been installed, but it was possible that the power was actually provided by the fusion reactor that had been installed centuries ago by the Space-Agers themselves.

The air we were breathing was produced by a Space-Age atmosphere plant that had been designed for actual space stations! It was a frightening, and at the same time, a thrilling feeling: our lives were dependent on actual functioning Space-Age equipment.

It was almost like stepping back in time.

The corridor made a right-angle turn and became a downward-sloping ramp.

The ramp leveled off after a few dozen feet, passed some crumbling rums, inset into one of the walls, apparently a ruined shop of some strange sort with massive chairs bolted to the floor and pieces of mirror still clinging to patches of its walls, and suddenly opened out into a wide, low, cavelike space lit dimly and erratically by ancient Space-Age perma-bulbs which still functioned in many places along the grime-encrusted ceiling.

It was the strangest room, if you could call it that, that I had ever been in.

The ceiling seemed horribly low, lower even than it actually was, because the room seemed to go on under it indefinitely, in all sorts of seemingly random directions.

Its boundaries faded off into shadows and dim lights and gloom; I couldn’t see any of the far walls.

It was impossible to feel exactly claustrophobic in a place like that, but it gave me an analogous sensation without a name, as if the ceiling and the floor might somehow come together and squash me.

Strange figures shuffled around in the gloom, moving, about slowly and aimlessly.

Other figures sat singly or in small groups on the bare filthy floor.

Most of the subway dwellers were well under five feet tall.

Their shoulders were deeply hunched, making them seem even shorter, and their bodies were thin, rickety, and emaciated under the tattered and filthy scraps of multicolored rags which they wore.

I was deeply shocked.

I don’t really know what I had expected, but I certainly had not been prepared for the unmistakable aura of diminished humanity which these pitiful creatures exuded even at a distant first glance.

Immediately before us was a kind of concrete hut.

It was pitted with what looked like bullet scars, and parts of it were burned black.

It had tiny windows, one of which still held some rotten metal grillwork.

Apparently it had been a kind of sentry-box, perhaps during the Panic of the Century itself.

A complex barrier cut off the section where we stood from the main area of the subway station.

It consisted of a ceiling-to-floor metal grillwork fence on either side of a line of turnstiles.

On either side of the line of turnstiles, gates in the fence clearly marked exit in peeling white-and-black enamel had been crudely welded shut; by the look of the weld, perhaps more than a century ago.

On the other side of the barrier stood a male subway dweller wearing a kind of long shirt patched together out of every conceivable type and color of cloth and rotting away at the edges and in random patches.

He stood staring at us, or at least with his deeply squinted expressionless eyes turned in our direction, rocking back and forth slightly from the waist, but otherwise not moving.

His face was unusually pallid even for an American, and every inch of his skin and clothing was caked with an incredible layer of filth.

Ignoring the subway dweller as thoroughly as that stooped figure was ignoring us, Ryan led us to the line of turnstiles and extracted a handful of small greenish yellow coins from a pocket.

“These are subway tokens,” he told us, dropping ten of the coins into a small slot atop one of the turnstiles.

“Space-Age money that was only used down here.

It’s good in all the vending machines, and in these turnstiles.

The subway dwellers still use the tokens to get food and water from the machines.

When I want more of these things, all I have to do is break open a vending machine, so don’t worry, admission isn’t costing us anything.

Just push your way through the turnstiles like this.”

He demonstrated by walking straight through the turnstile.

The turnstile barrier rotated a notch to let him through when he applied his body against it.

One by one we passed through the turnstile.

Michael Lumumba passed through immediately ahead of me, then paused at the other side to study the subway dweller, who had drifted up to the barrier, Lumumba looked down at the subway dweller’s face for a long moment; then a sardonic smile grew slowly on his face, and he said, “Hello, honkie, how are things in the subway?” The subway dweller turned his eyes in Lumumba’s direction.

He did nothing else.

“Hey, just what are you, some kind of cretin?” Lumumba said as Ryan, his face flushed red behind his pallor, turned in his tracks and started back toward Lumumba.

The subway dweller’s face did not change expression; in fact, it could hardly have been said to have had an expression in the first place.

“I think you’re a brain-damage case, honkie.”

“I told you not to talk to the subway dwellers!” Ryan said, shoving his way between Lumumba and the subway dweller.

“So you did,” Lumumba said coolly.

“And I’m beginning to wonder why.”

“They can be dangerous.”

“Dangerous? These little moronic slugs? The only thing these brainless white worms can be dangerous to is your pride.

Isn’t that it, Ryan? Behold the remnants of the great Space-Age honkies! See how they haven’t tile brains left to wipe the drool off their chins.”

“Be silent!” Kulongo suddenly bellowed with the authority of a chief in his voice.

Lumumba was indeed silenced, and even Ryan backed off as Kulongo moved near them.

But the self-satisfied look that Lumumba continued to give Ryan was a weapon that he was wielding, a weapon that the American obviously felt keenly.

Through it all, the subway dweller continued to rock back and forth, gently and silently, without a sign of human sentience.

Goddamn that black brother Lumumba and goddamn the stinking subway dwellers! Oh, how I hate taking these Africans down there.

Sometimes I wonder why the hell I do it.

Sometimes I feel there’s something unclean about it all, something rotten.

Not just the subway dwellers, though those horrible animals are rotten enough, but taking a bunch of stinking African tourists in there to look at them, and me making money off of it.

It’s a great selling point for the day-tour.

Those black brothers eat it up, especially the cruds like Lumumba, but if I didn’t need the money so bad, I wouldn’t do it.

Call it patriotism, maybe.

I’m not patriotic enough not to take my tours to see the subway dwellers, but I’m patriotic enough not to feel too happy with myself about it.

Of course, I know what it is that gets to me.

The subway dwellers are the last direct descendants of the Space-Agers, in a way the only piece of the Space Age still alive, and what they are is what Lumumba said they are: slugs, morons, and cretins.

And physical wrecks on top of it.

Lousy eyesight, rubbery bones, rotten teeth, and if you find one more than five feet tall, it’s a giant.

They’re lucky to live to thirty.

There’s no

-

28:24

28:24

PukeOnABook

18 days agoRahan. Episode 175. By Roger Lecureux. The man from Tautavel. A Puke(TM) Comic.

44 -

LIVE

LIVE

The Bubba Army

21 hours agoShannon Sharpe FIRED after Sex Lawsuit - Bubba the Love Sponge® Show | 7/31/25

2,116 watching -

21:23

21:23

DeVory Darkins

1 day ago $8.02 earnedTrump makes STUNNING Admission regarding Epstein and WSJ settlement

20.3K101 -

8:14

8:14

MattMorseTV

16 hours ago $6.36 earnedTrump just DROPPED the HAMMER.

31.9K39 -

2:47:03

2:47:03

Patriot Underground

20 hours agoTruthStream RT w/ Joe & Scott (7.30.25 @ 5PM EST)

42.7K27 -

42:04

42:04

World2Briggs

16 hours ago $1.71 earnedRanking All 50 States By Natural Beauty Will Shock You!

10.4K1 -

42:46

42:46

The Kevin Trudeau Show Limitless

22 hours agoManifest Anything: The Secret Teachings of Kevin Trudeau

6.63K4 -

LIVE

LIVE

Culture Crack

2 hours ago🔴 FINISHING Games | Metal Gear Rising, Prototype 2, Callisto Protocol + Online Safety Act Discussion

40 watching -

5:18:09

5:18:09

saiyagamertv

6 hours agoIm ready to RUMBLE lets WIN!!

3.27K1 -

13:05

13:05

IsaacButterfield

1 day ago $1.11 earnedPedro Pascal Needs To Stop

9.51K6