Premium Only Content

Social Effects And Truth About Popular Culture Is Market Driven Kids-Sex-Drugs-Etc.

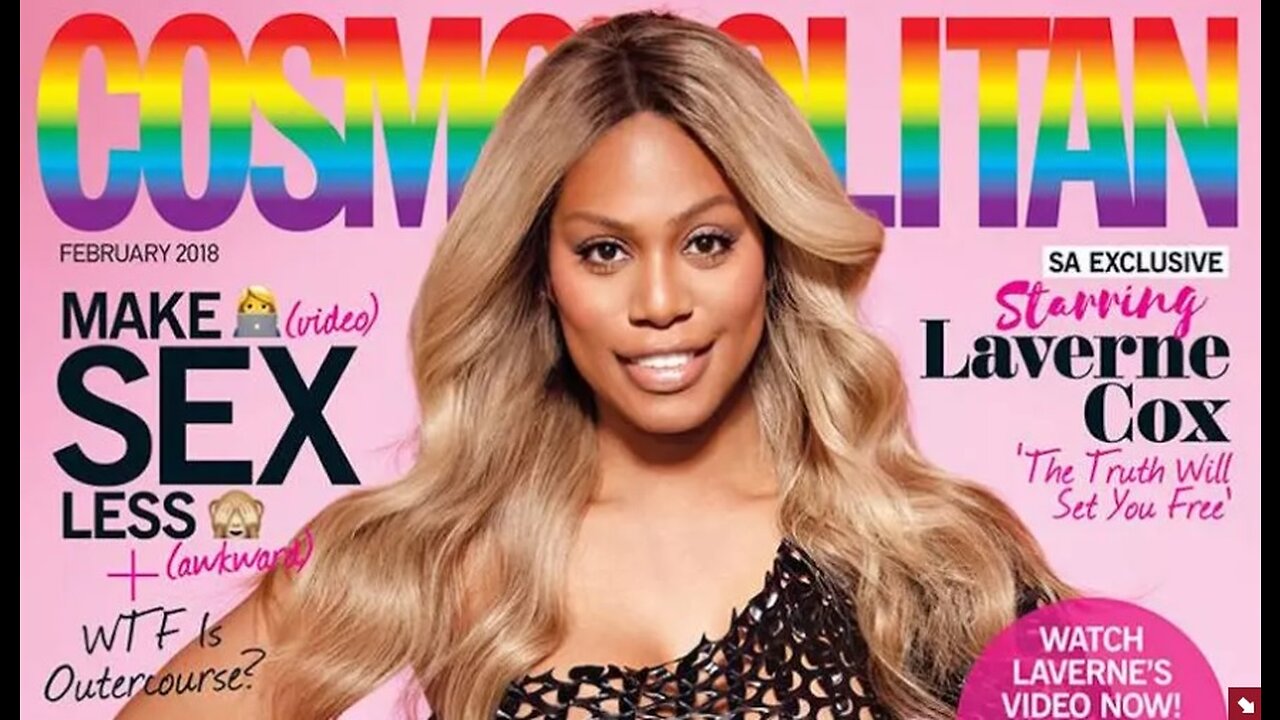

Truth About Popular Culture Is Market Driven Kids-Sex-Drugs-Cosmopolitan Magazine Cover and 10,000 Other Magazine Cover all over the world reveals everything wrong with the popular culture Have we completely lost our minds? In a word: Yes. Cosmopolitan Magazine has released its February issue, featuring the most recent transgender poster child Laverne Cox on its cover. There is so much wrong on this one page that it makes one’s head spin. Let me count the ways:

• The misogynistic insult of women by denying the biological fact of the female.

• The diminishing of the human being to little more than delusion and fantasy.

• The blatant disregard for science, i.e. genetics and physiology.

• The elevation of special “knowledge” (gnosis) that supersedes the natural and material.

This is little more than a placard for a culture — a cult — of deception and deceit; a snapshot of a people who have literally lost their mind.

When you dumb down the definition of the person to “being” gay, lesbian, queer, or straight; to “being” a homosexual, a transsexual or even heterosexual, you have just admitted you think those who have a given sexual appetite are actually defined by that desire. You are admitting you think “that’s just who they are” and that their very identity is nothing more than the sum total of their libidinous inclinations. Is this not the ultimate insult to the human being?

If the march for human dignity and human freedom means anything, it means we are the imago Dei! We are not the imago dog. We are not defined by our bellies or our libidos. We are not animals but, rather, we are men and women who have freewill in our behaviors, sexual or otherwise.

Even Gore Vidal understood this. He said, “There is no more such a thing as a homosexual person than there is a heterosexual person. These are behavioral adjectives,” Even though he was anything but a conservative, biblical Christian, Vidal knew no logically sound ontology or anthropology suggests the human being is defined merely by his or her behaviors or the adjectives used to describe him. He understood that the dignity of the person could not be diminished to merely what he or she wants to do.

Peter Beaulieu tells us that, “St. Augustine warned of … what he termed ‘fantastica fornicatio’ — the prostitution of the mind to its own fantasies.”

Glenn Stanton writes, “To identify people principally by their sexuality is to reduce people. … We should all reject this with great force. A person’s inherent and undeniable value is rooted in his membership in humanity, not his particularity, sexual or otherwise.”

“Central to my thesis,” says Daniel C. Mattson, “is that it is a mistake for anyone to say that he is … any sexual identity label currently in vogue today. I view these as graffiti painted on the side of the Holy of Holies, which deface human dignity and mock the image of God. …”

And Pope Francis declares, “It’s idolatry when a man or woman loses his or her ‘identity card’ as a child of God, and prefers to seek a god more to their own liking.”

Yes, we have lost our minds. Not only that, but we have lost our dignity and even our identity! In rejecting the obvious, we have most certainly exchanged the truth for a lie and sadly begun to worship the created rather than the Creator. In doing so, we have been given over to a reprobate mind and, thereby, can’t think our way out of a paper bag.

George Orwell is calling and he wants his royalties.

Endnote: It never ceases to amaze me how those who wave the rainbow banner of “love trumps hate” become so vitriolic and vengeful when presented with a logical, cogent argument challenging the vacuity of their own moral paradigm. The comments which will inevitably follow this article will be textbook examples of such self-refuting duplicity.

There will be shouts of “I can’t tolerate your intolerance. I hate you hateful people. I’m sure that nothing is sure, and I am absolutely confident there are no absolutes!” These inane responses are as predictable as the sunrise. Church leaders who fancy themselves as “progressives’ will respond with ad hominem attacks dripping with mockery and sarcasm. The Southern Poverty Law Center will label this commentary “hate speech.” Right-Wing Watch will once again construct a straw man that it can easily knock down, marginalize and malign. Those who claim to be champions of science will ignore science. Feminists will deny the biological fact of the feminine.

It would be funny if it weren’t so sad. Do these detractors not see the irony in their attitudes and action? Are they blind to the fact that they are sawing off the very rhetorical branch upon which they sit? Isaiah comes to mind: “Woe unto him who calls good evil and evil good…” and dare I add, woe unto him who calls love hate and hate love?

But, I suppose if this particular column does nothing else, it will serve to expose the fact that those who pretend to be champions of inclusion are really those most quick to exclude anyone who dares to suggest the obvious: Their emperor has no clothes, and their god is naked.

Pop Culture is Market Driven

The children and youth market is the most aggressively targeted market segment in the world. The reason? They have more disposable income and purchasing influence than any other age group. Consequently, marketers both use and shape the pop culture in an effort to influence the values, attitudes, and spending behaviors of our kids while developing lifetime brand loyalties. By using market research to better understand kids, marketers are then able to turn around and use what they’ve learned to connect with and influence those most vulnerable in our society.

Pop Culture is Fluid

In order to grab and maintain the attention of children and teens, pop culture must constantly reinvent itself. What is new, edgy and exciting today (styles, music, ideas, icons, etc.) will be obsolete tomorrow. Because kids are conditioned to look for and embrace whatever is fresh, the purveyors of pop stay busy examining their research in order to shape and develop the next big “thing.” As a result, pop culture is specific to place and time. While there is always some overlap, it’s necessary for those who study culture to look hard for and identify the specific nuances of the popular culture in their unique place and time.

Pop Culture is Pervasive

Wherever there are people, there will be popular culture. It is inescapable. Students cannot be sheltered from it. Even if they don’t engage the primary outlets themselves, they live and move in a peer society influenced by the pop culture. In today’s world, the advent of MTV and the Internet has facilitated the effective exportation of North American youth culture around the globe. While there are unique aspects from place to place, popular culture is everywhere and as a result, has facilitated the growth of a globalized youth culture. It has touched and shaped virtually all social institutions including the school, church, home, and community.

Pop Culture is Entertaining

Because it is market driven, pop culture must grab the attention of children and teens in order to survive and develop. It enters into their lives through a plethora of outlets, grabbing and holding their attention and allegiance by design. In the increased absence of stability and influence from the traditional institutions of home, church, and school, young people seek out pop culture to fill their time and, in some cases, help them forget their pain. Because it must be constantly developed and updated, pop culture’s “newness” increases its effectiveness to entertain.

Pop Culture is Unifying

In a world marked by relational breakdown, young people long for connections. Pop culture serves as a common thread that runs through the lives of children and teens, giving them a common experience, shared allegiances, and a place to belong. Pop culture binds children and teens together.

Sex, drugs and rock 'n roll is a modern variation of Wine, women and song. In the 20th century, particularly in Western usage, the expression "sex, drugs and rock and roll" often is used to signify essentially the same thing. The terms correspond to women, wine and song with edgier and updated vices. The term came to prominence in the sixties as rock and roll music, opulent and intensely public lifestyles, as well as libertine morals championed by hippies, came into the mainstream.

The rock and roll lifestyle was popularly associated with sex and drugs. Many of rock and roll's early stars (as well as their jazz and blues counterparts) were known as hard-drinking, hard-living characters. During the 1960s a decadent lifestyle of many stars became more publicly known, aided by the growth of the underground rock press which documented such excesses, often in exploitative fashion. Musicians had always attracted attention from the opposite sex; groupies (girls who followed musicians) spent time with and often did sexual favors for band members, appeared in the 1960s. While some rock groups eschewed such attention in favor of long-term relationships, other groups and artists did little to discourage it, and many tales (both true and exaggerated) of sexual escapades became part of rock music legacy during the heyday of the rock era. As the heyday was over rock lost a lot of its connection with sex while Rap, R&B and later on Pop have far more sexual content in there songs than rock and have also took over the idea of artists being sex symbols.

Drugs were often a big part of the rock music lifestyle. In the 1960s, psychedelic music arose; some musicians encouraged and intended listeners of psychedelic music to be under the influence of LSD or other hallucinogenic drugs as enhancements to the listening experience. Jerry Garcia of the rock band Grateful Dead said "For some people, taking LSD and going to Grateful Dead show functions like a rite of passage.... we don't have a product to sell; but we do have a mechanism that works."

The popularity and promotion of recreational drug use by musicians may have influenced use of drugs and the perception of acceptability of drug use among the youth of the period. When the Beatles, once marketed as clean-cut youths, started publicly acknowledging using Cannabis, many fans followed. Journalist Al Aronowitz wrote "...whatever the Beatles did was acceptable, especially for young people. Pretty soon everybody was smoking it, and it seemed to be all right." The relationship of rock music to the hippie and counterculture movements, which espoused use of marijuana and other drugs, is complex and intertwined, and it is not always clear in which direction influence flowed. What is clear is that by the end of the 1960s, drugs and rock music were part of a common youth scene and that both some rock musicians and some rock fans were experimenting with many types of drugs.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s however, much of the rock and roll cachet associated with drug use dissipated as rock music suffered a series of drug-related deaths, including the 27 Club member deaths of Brian Jones, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, and Jim Morrison. Although some amount of drug use remained common among rock musicians, a greater respect for the dangers of drug consumption was observed, and many anti-drug songs became part of the rock lexicon, notably "The Needle and the Damage Done" by Neil Young (1972).

Many rock musicians, including John Lennon, Jimmy Page, Keith Richards, Eric Clapton, Pete Townshend, Steven Tyler, Scott Weiland, Ozzy Osbourne and others, have acknowledged battling addictions to many substances including cocaine and heroin; many of these have successfully undergone drug rehabilitation programs, but others have died. In the early 1980s, along with the rise of the band Minor Threat, the straight edge lifestyle became popular, especially with young adults. The straight edge philosophy of abstinence from recreational drugs, alcohol, tobacco, and sex became associated with hardcore punk music through the years, and both remain popular with youth today. Many rock stars who suffered from drugs and quit or those who were close to drug abusers that died have supported rehabs and have raised awareness about the danger of drugs.

The lessons of the excesses of the earlier eras were sometimes ignored; some early punk rock was vociferous about promoting the abuse of drugs. Late 1970s acts such as The Stranglers, The Psychedelic Furs, and The Only Ones reflected their use of heroin in their lyrics in a fashion that sometimes seemed to cross over into advocacy. Later bands such as Guns N' Roses, Jane's Addiction, Primal Scream and Ministry movement of the 1980s were associated with a resurgence in abuse of heroin and other hard drugs. During the early 90s and even before so, Christian influences came into play as many Christian bands and older musicians who became born again frowned upon the rock 'n' roll life style of the 60s and 70s. More recently, it has mainly been rap and hip hop, (and a few electronica) acts which have been glamorizing and promoting drug use in songs. Although only a few current rock acts like The Libertines and Brian Jonestown Massacre have been as well. However, the lifestyle of most rock stars nowadays falls within the social norm. An example of this trend would be the formerly drug-abusing Red Hot Chili Peppers, who have since cleaned up their act. Several teenagers today look to rock as an alternative to the offensive lyrics and values of gangsta rap and hip hop.

Social effects of rock music The popularity and worldwide scope of rock music resulted in a powerful impact on society. Rock and roll influenced daily life, fashion, attitudes and language in a way few other social developments have equalled. As the original generations of rock and roll fans matured, the music became an accepted and deeply interwoven thread in popular culture. Beginning in the early 1950s, rock songs and acts began to be used in a few television commercials; within a decade this practice became widespread, and rock music also featured in film and television program soundtracks.

Race

In the crossover of African American "race music" to a growing white youth audience, the popularization of rock and roll involved both black performers reaching a white audience and white performers appropriating African-American music.

Rock and roll appeared at a time when racial tensions in the United States were entering a new phase, with the beginnings of the civil rights movement for desegregation, leading to the Supreme Court ruling that abolished the policy of "separate but equal" in 1954, but leaving a policy which would be extremely difficult to enforce in parts of the United States. The coming together of white youth audiences and black music in rock and roll, inevitably provoked strong white racist reactions within the US, with many whites condemning its breaking down of barriers based on color. Many observers saw rock and roll as heralding the way for desegregation, in creating a new form of music that encouraged racial cooperation and shared experience. > Many authors have argued that early rock and roll was instrumental in the way both white and black teenagers identified themselves.

Sex and drugs

The rock and roll lifestyle was popularly associated with sex and drugs. Many of rock and roll's early stars (as well as their jazz and blues counterparts) were known as hard-drinking, hard-living characters. During the 1960s the lifestyles of many stars became more publicly known, aided by the growth of the underground rock press. Musicians had always attracted attention of "groupies" (girls who followed musicians) who spent time with and often performed sexual favors for band members.

As the stars' lifestyles became more public, the popularity and promotion of recreational drug use by musicians may have influenced use of drugs and the perception of acceptability of drug use among the youth of the period. For example, when in the late 1960s the Beatles, who had previously been marketed as clean-cut youths, started publicly acknowledging using LSD, many fans followed. Journalist Al Aronowitz wrote "...whatever the Beatles did was acceptable, especially for young people." Jerry Garcia, of the rock band Grateful Dead said, "For some people, taking LSD and going to Grateful Dead show functions like a rite of passage ... we don't have a product to sell; but we do have a mechanism that works."

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, much of the rock and roll cachet associated with drug use dissipated as rock suffered a series of drug-related deaths, including the 27 Club-member deaths of Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin and Jim Morrison. Although some amount of drug use remained common among rock musicians, a greater respect for the dangers of drug consumption was observed, and many anti-drug songs became part of the rock lexicon, notably "The Needle and the Damage Done" by Neil Young (1972).

Many rock and pop musicians, including John Lennon, Paul McCartney, Mick Jagger, Bob Dylan, Jerry Garcia, Stevie Nicks, Jimmy Page, Keith Richards, Bon Scott, Eric Clapton, Pete Townshend, Brian Wilson, Carl Wilson, Dennis Wilson, Steven Tyler, Scott Weiland, Sly Stone, Ozzy Osbourne, Mötley Crüe, Layne Staley, Kurt Cobain, Lemmy, Bobby Brown, Buffy Sainte Marie, Dave Matthews, David Crosby, Anthony Kiedis, Dave Mustaine, David Bowie, Richard Wright, Phil Rudd, Phil Anselmo, James Hetfield, Kirk Hammett, Joe Walsh, Julian Casablancas and others, have acknowledged battling addictions to many substances including alcohol, cocaine and heroin; many of these have successfully undergone drug rehabilitation programs, but others have died.

In the early 1980s. along with the rise of the band Minor Threat, a straight edge lifestyle became popular. The straight edge philosophy of abstinence from recreational drugs, alcohol, tobacco and sex became associated with some hardcore punks through the years, and both remain popular with youth today.

Fashion

Rock music and fashion have been inextricably linked. In the mid-1960s of the UK, rivalry arose between "Mods" (who favoured 'modern' Italian-led fashion) and "Rockers" (who wore motorcycle leathers), each style had their own favored musical acts. (The controversy would form the backdrop for The Who's rock opera Quadrophenia). In the 1960s, The Beatles brought mop-top haircuts, collarless blazers, and Beatle Boots into fashion.

Rock musicians were also early adopters of hippie fashion and popularised such styles as long hair and the Nehru jacket. As rock music genres became more segmented, what an artist wore became as important as the music itself in defining the artist's intent and relationship to the audience. In the early 1970s, glam rock became widely influential featuring glittery fashions, high heels and camp. In the late 1970s, disco acts helped bring flashy urban styles to the mainstream, while punk groups began wearing mock-conservative attire, (including suit jackets and skinny ties), in an attempt to be as unlike mainstream rock musicians, who still favored blue jeans and hippie-influenced clothes.

Heavy Metal bands in the 1980s often favoured a strong visual image. For some bands, this consisted of leather or denim jackets and pants, spike/studs and long hair. Visual image was a strong component of the glam metal movement.

In 1981, MTV was formed, marking a large shift in the music world. Because MTV would become such a cultural force, the young would look toward MTV. Fashion happened to be one of those cultural centers that the Television company would have a great effect on. With debuts like Madonna's Iconic underwear-as-outerwear look and the companies featuring heavy metal as well as new wave and other genera that would go to promote each artist's brand of fashion into the greater culture, because of the sheer amount of visibility that MTV gave these artist through music videos and other content that the television channel had.

In the early 1990s, the popularity of grunge brought in a punk influenced fashion of its own, including torn jeans, old shoes, flannel shirts, backwards baseball hats, and people grew their hair against the clean-cut image that was popular at the time in heavily commercialized pop music culture.

Musicians continue to be fashion icons; pop-culture magazines such as Rolling Stone often include fashion layouts featuring musicians as models.

Authenticity

Rock musicians and fans have consistently struggled with the paradox of "selling out"—to be considered "authentic", rock music must keep a certain distance from the commercial world and its constructs; however it is widely believed that certain compromises must be made in order to become successful and to make music available to the public. This dilemma has created friction between musicians and fans, with some bands going to great lengths to avoid the appearance of "selling out" (while still finding ways to make a lucrative living). In some styles of rock, such as punk and heavy metal, a performer who is believed to have "sold out" to commercial interests may be labelled with the pejorative term "poseur".

If a performer first comes to public attention with one style, any further stylistic development may be seen as selling out to long-time fans. On the other hand, managers and producers may progressively take more control of the artist, as happened, for instance, in Elvis Presley's swift transition in species from "The Hillbilly Cat" to "your teddy bear". It can be difficult to define the difference between seeking a wider audience and selling out. Ray Charles left behind his classic formulation of rhythm and blues to sing country music, pop songs and soft-drink commercials. In the process, he went from a niche audience to worldwide fame. Bob Dylan faced consternation from fans for embracing the electric guitar. In the end, it is a moral judgement made by the artist, the management, and the audience.

Charitable and social causes

Love and peace were very common themes in rock music during the 1960s and 1970s. Rock musicians have often attempted to address social issues directly as commentary or as calls to action. During the Vietnam War the first rock protest songs were heard, inspired by the songs of folk musicians such as Woody Guthrie and Bob Dylan, which ranged from abstract evocations of peace Peter, Paul and Mary's "If I Had a Hammer" to blunt anti-establishment diatribes Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young's "Ohio". Other musicians, notably John Lennon and Yoko Ono, were vocal in their anti-war sentiment both in their music and in public statements with songs such as "Imagine", and "Give Peace a Chance".

Famous rock musicians have adopted causes ranging from the environment (Marvin Gaye's "Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology)") and the Anti-Apartheid Movement (Peter Gabriel's "Biko"), to violence in Northern Ireland (U2's "Sunday Bloody Sunday") and worldwide economic policy (the Dead Kennedys' "Kill the Poor"). Another notable protest song is Patti Smith's recording "People Have the Power." On occasion this involvement would go beyond simple songwriting and take the form of sometimes-spectacular concerts or televised events, often raising money for charity and awareness of global issues.

Rock music as social activism reached a milestone in the Live Aid concerts, held July 13, 1985, which were an outgrowth of the 1984 charity single "Do They Know It's Christmas?" and became the largest musical concert in history with performers on two main stages, one in London, England and the other in Philadelphia, USA (plus some other acts performing in other countries) and televised worldwide. The concert lasted 16 hours and featured nearly everybody who was in the forefront of rock and pop in 1985. The charity event raised millions of dollars for famine relief in Africa. Live Aid became a model for many other fund-raising and consciousness-raising efforts, including the Farm Aid concerts for family farmers in North America, and televised performances benefiting victims of the September 11 attacks. Live Aid itself was reprised in 2005 with the Live 8 concert, to raise awareness of global economic policy. Environmental issues have also been a common theme, one example being Live Earth.

Religion

Songwriters such as Pete Townshend have explored these spiritual aspects within their work. The common usage of the term "rock god" acknowledges the religious quality of the adulation some rock stars receive. John Lennon became infamous for a statement he made in 1966 that The Beatles were "more popular than Jesus". However, he later said that this statement was misunderstood and not meant to be anti-Christian.

Iron Maiden, Ozzy Osbourne, King Diamond, Alice Cooper, Led Zeppelin, Marilyn Manson, Slayer and numerous others have also been accused of being satanists, immoral or otherwise having an "evil" influence on their listeners. Anti-religious sentiments also appear in punk and hardcore. There's the example of the song "Filler" by Minor Threat, the name and famous logo of the band Bad Religion and criticism of Christianity and all religions is an important theme in anarcho-punk and crust punk.

Christianity

Christian rock, alternative rock, metal, punk, and hardcore are specific, identifiable genres of rock music with strong Christian overtones and influence. Many groups and individuals who are not considered to be Christian rock artists have religious beliefs themselves. For example; The Edge and Bono of U2 are a Methodist and an Anglican, respectively; Bruce Springsteen is a Roman Catholic; and Brandon Flowers of The Killers is a Latter Day Saint. Carlos Santana, Ted Nugent, and John Mellencamp are all other examples of rock stars who profess some form of Christian faith.

However, some conservative Christians single out the music genres of hip hop and rock as well as blues and jazz as containing jungle beats, or jungle music, and claim that it is a beat or musical style that is inherently evil, immoral, or sensual. Thus, according to them, any song in the rap, hip hop and rock genres is inherently evil because of the song's musical beat, regardless of the song's lyrics or message. A few even extend this analysis even to Christian rock songs.

Christian conservative author David Noebel is one of the most notable opponents of the existence of jungle beats. In his writings and speeches, Noebel held that the use of such beats in music was a communist plot to subvert the morality of the youth of the United States. Pope Benedict XVI was quoted as saying, according to the British Broadcasting Corporation, that "Rock... is the expression of the elemental passions, and at rock festivals it assumes a sometimes cultic character, a form of worship, in fact, in opposition to Christian worship."

Satanism

Some metal bands use demonic imagery for artistic and/or entertainment purposes, though many do not worship or believe in Satan. Ozzy Osbourne is reported to be Anglican and Alice Cooper is a known born-again Christian. In some cases, though, metal performers have expressed satanic views. Numerous others in the early Norwegian black metal scene were Satanists. The most known example of this is Euronymous, who claimed that he worshiped Satan as a god. Varg Vikernes (back then called "the Count" or Grishnak) has also been called a Satanist, even through he has rejected that label. Even within this localized musical subgenre, however, the arson attacks against Christian churches and other centers of worship were condemned by some prominent figures within the Norwegian black metal scene, such as Kjetil Manheim.

John Lennon on Christianity:

Christianity will go. It will vanish and shrink. I needn't argue with that; I'm right and I will be proved right. We're more popular than Jesus now; I don't know which will go first — rock and roll or Christianity. Jesus was all right, but his disciples were thick and ordinary. It's them twisting it that ruins it for me.

One of the most controversial statements Lennon ever made, this was published in England's Evening Standard newspaper (4 March 1966) as part of an interview with writer Maureen Cleave. This single quote (taken out of context — Lennon was often misquoted as stating the Beatles were "bigger than Jesus") was to spark protests across the Bible Belt in America. Beatles records were burned en masse, and the Ku Klux Klan burned a Beatles effigy and nailed Beatles albums to a burning cross. The band members were dismissive of this, as they pointed out that first the people had to buy the albums in order to burn them.

I suppose if I had said television was more popular than Jesus, I would have gotten away with it. I'm sorry I opened my mouth. I'm not anti-God, anti-Christ, or anti-religion. I wasn't knocking it or putting it down. I was just saying it as a fact and it's true more for England than here. I'm not saying that we're better or greater, or comparing us with Jesus Christ as a person or God as a thing or whatever it is. I just said what I said and it was wrong. Or it was taken wrong. And now it's all this. News conference in Chicago, where he apologized for the above statement, which was accepted by the Vatican. (11 August 1966)

As educators in the humanities field, one of the key ideas we seek to share with our students is the notion that all literary texts are ensnared within a dynamic web of socio-cultural discourse. However, in our haste to reveal the ideological and socio-historical context of such cultural products, we often limit our pedagogical endeavours to traditionally “literary” or “highbrow” works. As a result, we litter our curriculums with canonical texts which, to many students, seem removed from their own experiences and whose cultural concerns are intimidating and alien to them.

Responding to this disturbingly common experience, I believe that one solution which presents itself to lecturers and tutors is to transgress the accepted boundaries of the academic canon. To do this we must explore how more populist texts can function as potent manifestations of ideological paradigms, cultural conflicts and socio-historical discourses. In contrast to some of the more linguistically and culturally alienating works studied in many conventional literature courses, popular culture appeals to undergraduate students as a dynamic and energetic entity: its language and thematic concerns are not only accessible to the average student, but actively engaging. This post therefore seeks to explore the value of and rationale behind teaching critical skills through populist texts by sharing my experience of designing and teaching a popular culture studies module. In doing so, I will connect my strategies to the wider academic discourse surrounding the role of mainstream entertainment in the classroom.

miranda

The Day the Earth Stood Still. 20th Century Fox, 1951.

While universities should remain firm in their commitment to presenting students with texts that challenge them intellectually, the introduction of popular culture to the classroom can provide a useful means of supplementing the study of canonical works. The academic analysis of popular entertainment can serve to bridge the chasm between traditionally “highbrow” literature and the more populist media that often defines a student’s pre-existing cultural experience. One educator, Rana Houshmand, describes this practice as the “scaffolding [of] difficult literacy skills” – a strategy which has proven remarkably successful in foundational projects where the critical analysis of hip-hop lyrics has been used as means of connecting students’ contextual experiences with the analytical skills developed in the classroom. This strategy has also been used to facilitate understandings of theory and philosophy in more advanced courses which utilise video game character tropes to interrogate, in relatable terms, Judith Butler’s notion of performativity in the construction of hegemonic gender roles.

The Module

Two years ago, in an attempt to broaden the scope of literary analysis practiced at undergraduate level, I designed an interactive seminar aimed at second-year university students entitled “Watching the Skies: Twentieth-Century American Science Fiction”. Encompassing such landmarks of the genre as the novels of Richard Matheson and John W. Campbell, cinematic works like The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951) and Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956), and the classic television series The Twilight Zone (1959-1964), the seminar aimed to introduce students to the different ways in which these texts adapted the conventions of the science fiction genre in order to comment upon and critique the major socio-cultural concerns of mid-twentieth-century America.

miranda

Family watching television, 1958. Source: National Archives and Records Administration.

The Planning Stages

While the idea for this module emerged from my desire to render literary criticism more accessible, there were numerous practical concerns which had to be taken into account when designing this seminar.

Where will my module fit within the University and the Course Curriculum?

Firstly, I had to consider the position of my module and the role it would serve within the wider undergraduate English course offered by my department. Although my university offers a broad range of literary studies modules, incorporating subjects as diverse as Anglo-Saxon poetry and experimental European cinema, twentieth-century popular culture does not feature prominently on the curriculum. Consequently, in the written proposal submitted to the School of English selection committee, I presented my module as filling a gap in an otherwise comprehensive degree programme, framing the course as a unique opportunity for students to engage critically with frequently overlooked, yet highly influential, cultural artefacts. Furthermore, I was careful to establish that the introduction of a popular culture studies module would not supplant the teaching of canonical works, but rather compliment them. I also advocated for the inclusion of texts that normally fall outside the purview of mainstream academic analysis on the basis that a lack of secondary critical materials would encourage students to rely on and further develop their own capacity for independent thinking.

Teaching History and Theory through Popular Culture

The next major factor informing the design of this module was the issue of structuring the course so that it would provide students not only with a broad overview of twentieth-century science fiction, but also serve as an effective platform from which to explore complex issues such as literary theory, ideology and the socio-cultural production of the text. Basing my pedagogical approach on the educator Ernest Morrell’s assertion that the critically literate student should be able to understand the “socially constructed meaning embedded in texts as well as the political and economic contexts in which the texts are produced”, the theoretical framework informing the creation of this course was grounded in genre theory and a historicist approach to literary analysis. While this practice of exploring literature through a largely socio-historical lens can be viewed as dismissive of those facets of literary production that transcend historical context, I felt that in order to adhere to the time constraints and maintain a cohesive thematic focus a single critical perspective would prove a more effective means of structuring the seminar content.

Moreover, in the case of popular entertainment, which is generally mass-produced and often intended as disposable cultural ephemera, the immediacy of populist texts allows them to engage directly with current social and political discourses, reflecting in their iconography and narrative content the prevailing cultural preoccupations of their era. The historicist approach to literary studies thus functions as an ideal approach to the study of science fiction, a genre which, throughout much of its history, has employed highly imaginative narrative tropes for the specific purpose of interrogating a wide range of topical social, political and cultural issues.

Designing the Module

Consisting of twelve two-hour seminars spread across a single term, the module was divided into three sections, with each section focusing on a key social or cultural concern of the post-war period and evaluating how the unique narrative conventions of science fiction can be employed to explore these issues in a variety of innovative ways. In doing so, I identified three key issues that shaped the mid-twentieth century popular imagination – the growth of American anti-communist paranoia, the birth of the Atomic Age and the post-war evolution of gender roles – and built the course content around these subjects. I also ensured that this historicised approach to teaching science fiction would be prefaced by a discussion of genre theory so that students could learn to identify how categorisations such as science fiction serve as linguistic shorthand for a set of “stock” imaginative tropes – character archetypes, narrative structures, recurring aesthetic patterns and intellectual preoccupations – that are utilised as “stand-ins” for broader concepts.

Finally, I compiled a list of learning outcomes that would ultimately become the criteria by which I judged the success of the module. My educational objectives stated that upon completion of this course students should be able to:

critically read and analyse a selection of post-World War II American science fiction texts

compare the manner in which these texts utilise the thematic conventions of the science fiction genre in order to comment upon a wide variety of social and political issues

discuss the cultural and historical context which framed the development of the science fiction genre as a vehicle for social commentary and criticism

define terms and concepts central to relevant aspects of genre theory

apply these terms and concepts to the set texts.

The capacity of students to successfully achieve these educational goals was measured through a series of written assignments and oral presentations. Less quantifiable learning outcomes, such as the ability of participants to articulate highly personal responses to the texts, were observable through student engagement with informal classroom-based discussions.

Creative Teaching

I designed the seminar to be interactive and grounded in an ongoing dialogue about the nature and function of genre. As such, I based the format of the seminar on the increasingly popular pedagogical method of Enquiry Based Learning (EBL) – a form of carefully structured group work “stimulated by enquiry including: project work, small-scale investigation and problem-based learning”.

As an illustration of how this technique works in practice, I would like to provide a brief overview of a class I taught based around one of the most popular novels on my course, Ira Levin’s 1972 feminist satire The Stepford Wives.

miranda

Ira Levin’s novel employs the fantastic concept of suburban husbands replacing their progressively-minded wives with subservient robots. In her seminar Corcoran used this text to interrogate various cultural discourses surrounding female autonomy and imperilled post-war masculinity. First edition book cover, Random House, 1972.

During the first part of The Stepford Wives seminar I provided the students with a comprehensive overview of post-war America’s changing attitudes to gender and sexuality, incorporating everything from how societal desires to contain female sexuality were manifested in the voluminous bodices and skirts of 1950s fashion to the emergence of Second-Wave feminism. In doing so, I relied heavily on contemporary advertising material to illustrate how changing feminine ideals were promoted in popular media and to underscore how women, as social subjects, were constructed by external cultural and economic forces. I then divided the students into small groups and provided each group with additional post-war advertisements that presented socially-constructed feminine ideals in a variety of contexts, from the domestic to the sensual.

In the second half of the seminar I used the EBL method to get the students to imagine how the narrative and aesthetic staples of the science fiction genre could be used to represent and even critique the popular conceptions of womanhood depicted in these advertisements. This imaginative exercise was enthusiastically embraced by the students who constructed diverse narratives in which adverts that tie consumerist femininity to modern domestic technology were reconfigured as original stories about cybernetics, while students felt that ads emphasising invasive modern beauty techniques could be reconceived as speculative tales about genetic engineering. The students were empowered to reach their own conclusions about the relationship between science/technology and feminine identity, a critical process which allowed them to construct their own theoretical framework through which to the read the novel.

While I personally felt that the overall cohesiveness of the module could have been improved through a narrowing of the textual and thematic focus of the course, both student evaluation forms and the consistently high grades achieved by participants indicated that the module was successful.

miranda

An example of an ad Corcoran used in her Enquiry Based Learning (EBL) seminars. Print advertisement from the Hoover Company, early 1950s.

Having designed a successful and popular course for second-year students, I could subsequently identify numerous innovative ways in which a similar module could be tailored to the different educational requirements of other year groups. For instance, a broader, more simplistic survey of science fiction works could be combined with a basic foundations of critical practice course in order to introduce first-year students to key theoretical concepts in areas such as narratology, gender studies and even post-structuralism. Similarly, a more in-depth and specialised course focusing on a specific facet of the science fiction genre, for example the representation of artificial intelligence in “hard” sci-fi texts, could form the nucleus of a third-year, or even a Masters-level, course on scientific or technological ethics in contemporary literature. I found the integration of popular culture into the academic canon provides endless opportunities for the development of creative pedagogical philosophies and teaching practices.

For me, overall, the process of designing a seminar for the first time was a valuable learning experience as an educator, researcher and advocate of popular culture in academic curriculum. My first experience of creating an original module forced me to re-evaluate my own previously held notions about how academics communicate ideas.

Having formerly only shared my research at conferences attended by academics equally steeped in discipline-specific terminology and concepts, the opportunity to tailor complex ideas about history, literary genre, gender and politics to undergraduate students encouraged me to consider new ways of sharing knowledge. Moreover, while I have always advocated for popular entertainment as a worthwhile area of academic study, designing this module allowed me to see for the first time how truly useful popular culture can be as a pedagogical tool which communicates difficult concepts through a familiar cultural lexicon.

Our brand new Hip Hop and Rap HND pathway will kick off next academic year and we want to provide some important context ahead of time. In light of recent #BlackLivesMatter protests bringing to light racial inequalities, it feels vital to highlight hip-hop’s Black American roots. White audiences and society uses and commodifies, co-opts and even steals a Black culture a lot – and it is important we check ourselves wherever we can.

Students on the HND will also get a Hip-Hop Reading List alongside their primary course material, which outlines some great readings on the significance of hip-hop as Black pop culture – how it has been represented, received, and produced. The current Black Lives Matter protests evoke a familiar message that hip-hop has spoke since it began. For decades hip-hop has spoken truth to power and challenge the status-quo. Protest and resistance have been common elements of the music, evoking the fight for racial equality and communicating anger at socio-economic conditions that shaped the lives of many Black people. Today, not a lot has sadly changed and many of hip-hop’s messages are still incredibly relevant.

Since it emerged in the Bronx in the 70s and 80s, Hip-hop has become hugely influential – mainstream music, a “cultural and artistic phenomenon” and a multibillion-dollar global industry. It’s important to understand how hip hop came about within the historical context of the African American experience but it is also important not to fall into common cultural misconceptions and associations of hip hop. It can be interesting to examine how representations of Blackness operate in American pop culture and vital when approaching the subject as an area of study.

We owe many popular music forms to the Black community. Rock and Roll, Techno, Jazz, Disco – you name it. Some of these genres have been subject to ‘whitewashing’ throughout history, such as Elvis becoming known as the ‘King’ of Rock n’ Roll which was originally pioneered by African American musicians, or current fears that European electronic music is erasing its Black origins (read about the campaign called ‘Make Techno Black Again’).

Hip-hop is slightly different. For the most part it’s very much still read as ‘black culture’ – even synonymous with black culture (which can be problematically essentialist). Hip-hop culture is a global culture – we use, enjoy, implement, and borrow from the culture in music, fashion and elsewhere. Hip-Hop was born in New York of Black, Latino and marginalised communities, and hip-hop in the mainstream developed to largely to be seen as Black. Developing an awareness of ‘hip-hop history’ can be important to understanding how the contemporary west treats and represents Blackness and how Black popular culture works in the mainstream.

Born in the Bronx, New York in the 1970s in African American and Latino urban neighbourhoods, hip-hop was a fusion of various cultural forces and influences. It emerged in a period of “urban renewal” for American cities, with a new kind of resegregation happening and white-flight to the suburbs; terms like inner city and underclass were reinventing America’s racial vocabulary. In this midst of what Professor Trica Rose calls the “post-civil rights era ghetto segregation”, a flourishing new youth culture emerged. “Hip Hop is an oppositional cultural realm rooted in the socio-political and historical experiences and consciousness of economically disadvantaged urban black youth of the late 20th century,” as Layli Phillps says.

Hip-hop emerged in part, as a reaction to the socio-economic conditions in Black and Brown neighbourhoods. The culture was broad and not just about the music; beatboxing, DJing, street art, graffiti, dancing, braids, hairstyles all emerged as part of hip-hop culture. ‘Hip hop’ generally refers to the overall culture, while ‘rap’ (or MCing) referred to the rhyme creation and lyricism, originating in the battle raps that would take place on the streets.

Kickstarted by the likes of Grandmaster Flash, DJ Kool Herc and Afrika Bambaataa, music at first was largely party anthems, often played in block parties and in the underground scene (see the 1982 film Wild Style). “It was Herc who laid the groundwork for everything associated with Hip Hop today” says The Independent, “the Jamaican-born DJ would often speak over a rhythmic beat – known within the music genre as toasting, and at parties in his high-rise apartment, he would extend the beat of a record using two players, isolating the drum “breaks” by using a mixer to switch between the two – or as it’s more commonly know: scratching.”

The music was a product of its socio-economic conditions and it grew to actively express these too, giving it a political edge. Protest rap or conscious rap grew in the 80s and 90s with the likes of Public Enemy, De La Soul, A Tribe Called Quest, NAS, Mos Def, and N.W.A. – and would often make reference to the Black Power movement of the 50s/60s. It was a reactionary response to mainstream culture – an oppositional force. In the 80s early gangsta rap also emerged, (N.W.A., Ice T, KRS One, Eazy E, Westside Connection) and often crossed over into the political or protest.

Rappers have been criticising the violence of the police and law enforcement on Black people, particularly Black men, since the emergence of political conscious rap in the 80s. Hip-hop reflected and responded to various racial inequalities such as the American Prison Industrial Complex, where Black men are disproportionately incarcerated (what Michelle Alexander calls quite convincingly the ‘New Jim Crow‘), white police brutality against Black bodies, and the socio-economic conditions of Black urban communities leading to factors like Black on Black crime.

Once hip-hop entered the mainstream it became increasingly commoditised and increasingly consumed by white audiences. The ‘gangsta image’ was seized on in pop culture, and in this became a popular and essentialist way to view this generation of Black youth.

Hip-hop has a lot of important things to say. But as the culture became commodified and popular to the masses, certain things – like references to violence, ‘Thug’ or ‘gangsta’ lifestyles, and even misogynistic lyrics – were heightened in order to sell more records. Problematically these were often taken as literal representations of Black life and Black people often too got seen as synonymous with hip-hop. Many have argued that there is a lot more to be taken from hip-hop than these base-level assumptions and stereotypes.

“Many critics of hip hop tend to interpret lyrics literally as a direct reflection of the artist who performs them. They equate rappers with thugs, see rappers as a threat to the larger society, and then use this ‘causal analysis’ (that hip hop causes violence) to justify a variety of agendas: more police in black communities, more prisons to accommodate larger numbers of black and brown young people, and more censorship of expression. For these critics, hip hop is criminal propaganda. This literal approach, which extends beyond the individual to categorise an entire racial and class group, is rarely applied to violence-oriented mediums procured by whites,” says hip-hop scholar Tricia Rose.

Aspects of rap lyric and video content are continually criticised in the mainstream for its representation and treatment of women, although several critics (such as Tricia Rose and Imani Perry) have worked to reclaim black women’s positioning within the genre. There are many female participants in hip-hop culture – and have been since it first emerged. Studying the work of female artists can open up a space for more transgressive and nuanced interpretations of hip-hop culture, they say.

It is true that much of hip hop’s sexual politics (from male producers) involve demeaning representations of women, but the dialogue and interaction of the sexes in hip-hop is complex. Moreover, black female rappers have asserted a prominent space in hip hop and this deserves particular attention. From the start rappers like MC Lyte and Queen Latifah exploded onto the scene with empowering, assertive tracks like Ladies First and U.N.I.T.Y.

Conscious artists like Lauryn Hill and Erykah Badu have been hugely acclaimed and work to celebrate Black womanhood, and even the ‘female Gangsta rappers’ like Lil’ Kim and Foxy Brown arguably created some transgressive space for Black female performers in hip-hop. Overall several scholars have argued for a articulation for women’s role in early hip-hop and for highlighting the oppositional and empowering stance many of them hold.

In her book Black Noise, Tricia Rose explores rap’s sexual politics, looking at the ways black women rappers negotiate—either by resisting or unwittingly perpetuating—dominant sexual and racial narratives in American culture. She puts female rappers in dialogue with black male rappers, and argues that there is a conscious and race-specific negotiation of cultural terrain taking place.

Literature by black female writers such as Hazel Carby, Angela Davis and bell hooks also speaks to the complexity of black female expression and specifically the black American female experience – Rose sees this complexity as operational in mainstream hip hop spheres, and argues black female rappers have a voice worth exploring critically.

Since hip-hop has become such a global entity, it’s produced some of the world’s biggest stars. Many prominent artists like Ice Cube, Queen Latifah, Jay Z, Kanye and Will Smith have become what we could call a ‘mogul’ often crossing over into other industries like fashion or Hollywood and creally creating a brand out of their star identity, becoming incredible successful business people . Other creators in hip-hop like Russell Simmons (Def Jam) have become known as hip-hop moguls – entrepreneurs who are understood as coming from the ‘hip hop generation’.

These producers emerged during the period in which hip-hop became mass commodified, which eventually coincided with a political context of Neoliberalism. America’s Neoliberalism also introduced the concept of a post-racial society (prominently in the US, but also mirrored in the UK) – reinforced and/or determined in America by the election of President Obama, the first Black president. Illusions of a post-racial society worked alongside successful Black figures to creative an illusion that the US was rid of racial injustice – systemic or otherwise. In fact, long-standing racial inequalities still exist and many of hip-hop’s original arguments are still very much relevant.

“Many academics have argued that hip-hop was ‘complexly determined by some of the worst social trends associated with neoliberalism: soaring inequality, extreme marketisation, mass criminalisation, and chronic unemployment.’ While many political rappers adopted oppositional stances to these trends, mainstream hip-hop culture often celebrated materialism and enterprise with all the gusto of individuals who have ‘made it’ against terrible odds” says hip-hop scholar Eithne Quinn.

Today, hip-hop still has a political edge, arguably continues a return to the consciousness and resistance of some early protest hip-hop, and a step away from the hyper-commodified, hyper-sexualised versions of the music in the 90s/00s. Hip-hop is and was more than a music form, and has an enduring and particular significance. It became the voice of a generation – a generation who now lead the way with the #BlackLivesMatter movement.

“The hip-hop-savvy radicalism of #BlackLivesMatter has liberated commercial rap from its default modern setting — the one that birthed the breezy millennial perception that “hip-hop” was a synonym for a consumer market where rowdy, rhyming negro gentleman callers and ballers sold vernacular song and dance to an adoringly vicarious and increasingly whiter public – a fair portion of whom are undeniably apathetic to race politics and the New Jim Crow, per Michelle Alexander’s groundbreaking study of present-day judicial abuses,” commented Rolling Stone in 2015.

There’s so much to unpack in hip-hop, it’s impossible to cover it all in a short article – be it whiteness in hip-hop, it’s sexual politics, prosecuting rap, a hip-hop education or hip-hop filmmaking, we hope this has provided a small start to doing just that. While hip-hop must not been seen as the ‘blueprint’ for ‘describing’ the Black community or all African American people collectively, however it can be important to understand the impact and production of hip-hop in these specifically racial terms, and connect it to it’s history – and the arguments hip-hop has been making about the treatment of African Americans and Black people in the U.S (and UK) for decades.

Band Apologizes After Lead Singer Gets 'Carried Away' And Pees On Fan's Face During Concert Brass Against, a brass rock cover band known for their unique covers of songs by bands like RATM and Tool, has issued an apology after its lead singer, Sophia Urista, peed on a fan's face during a show at the Welcome to Rockville festival in Daytona Beach, Florida, on November 11, 2021. Urista pulled down her pants on stage and peed on a willing fan mid-song. The band posted an apology on Twitter, assuring fans that it wasn't a planned stunt. Urista is a former contestant on season 11 of The Voice back in 2016, who competed on Team Miley Cyrus. - https://youtu.be/9K7WjE5JbIU - Sophia Urista z Brass Against.

-

47:58

47:58

What If Everything You Were Taught Was A Lie?

25 days agoExposing Everyone And Everything A Epstein Survivor Interview Human Trafficking Child Sex Ring

5.17K5 -

LIVE

LIVE

Dear America

44 minutes agoIs Trump Going To Federalize DC TODAY?! + Biden Pardons VOIDED?!?!

10,107 watching -

LIVE

LIVE

Matt Kohrs

36 minutes agoMarket Open: NEW HIGHS INCOMING 🚀 🚀 🚀 || Live From Toronto

565 watching -

LIVE

LIVE

Wendy Bell Radio

4 hours agoThe Hunters Are Now The Hunted

4,031 watching -

LIVE

LIVE

Tate Speech by Andrew Tate

1 hour agoEMERGENCY MEETING EPISODE 113 - THE NEXT STAGE

9,909 watching -

1:19:40

1:19:40

JULIE GREEN MINISTRIES

2 hours agoLIVE WITH JULIE

32.1K118 -

LIVE

LIVE

LFA TV

14 hours agoLFA TV ALL DAY STREAM - MONDAY 8/11/25

7,512 watching -

LIVE

LIVE

Chicks On The Right

3 hours agoMTG fighting w/Levin, Pritzker humiliated by Welker, Mamdani squeals like a girl, and psychotic libs

1,816 watching -

LIVE

LIVE

The Bubba Army

2 days agoAlligator Alcatraz Closed?! - Bubba the Love Sponge® Show | 8/11/25

4,329 watching -

29:03

29:03

DeVory Darkins

15 hours ago $6.40 earnedDemocrat Governors painfully HUMILIATED Trump drops BRUTAL WARNING for DC officials

7.03K54