Premium Only Content

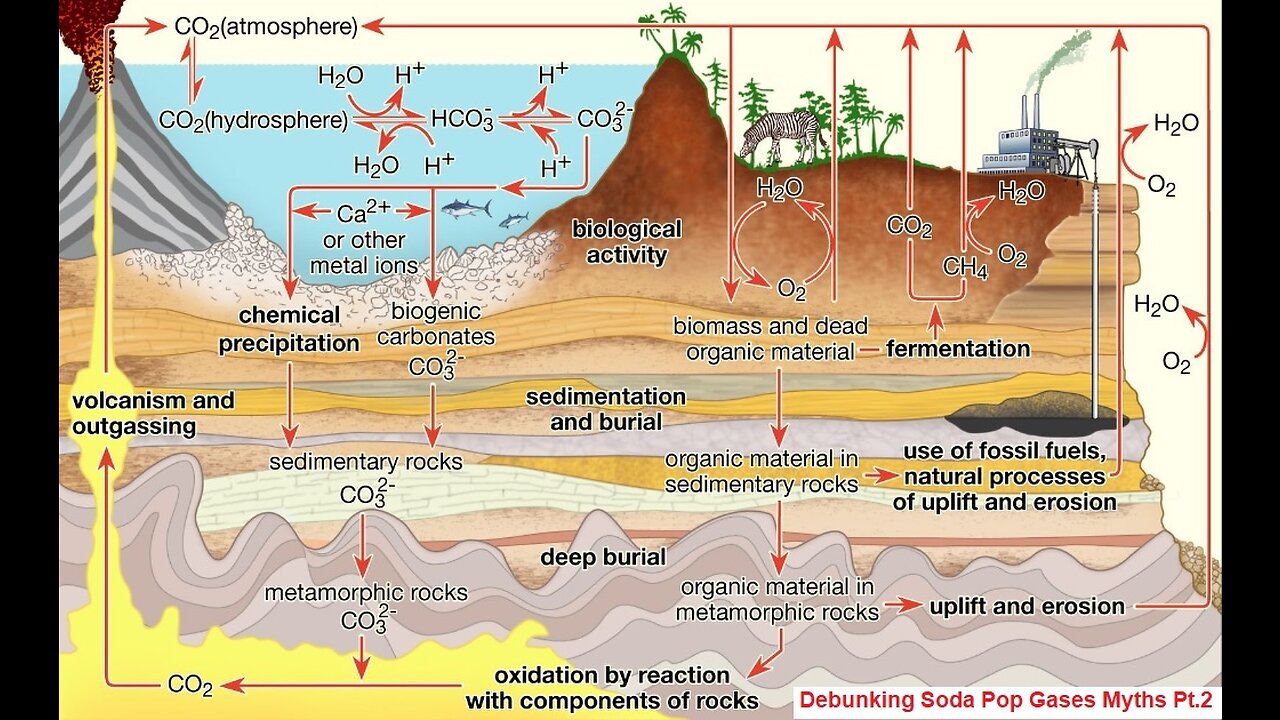

Debunking Soda Pop Gases Myths Pt.2 About Humans Are Not Causing Global Warming

Climate-change deniers are mistaken when they claim that factors other than our greenhouse gas emissions are causing global warming, whether they point to Milankovitch cycles, the Sun or volcanic eruptions. The data clearly shows that the predominant cause of current warming trends are manmade greenhouse gas emissions. Carbon dioxide concentrations are rising mostly because of the fossil fuels that people are burning for energy. Fossil fuels like coal and oil contain carbon that plants pulled out of the atmosphere through photosynthesis over many millions of years; we are returning that carbon to the atmosphere in just a few hundred. Since the middle of the 20th century, annual emissions from burning fossil fuels have increased every decade, from close to 11 billion tons of carbon dioxide per year in the 1960s to an estimated 36.6 billion tons in 2022.

(Part Two Words and Type From Part One)

Evidence for a cooler Mediterranean climate from 600 B.C. to 100 B.C. comes from remains of ancient harbors at Naples and in the Adriatic which are located about one meter (three feet) below current water levels. Further support for lower sea levels has been found on the North African coast, around the Aegean, the Crimea, and the eastern Mediterranean. Lower oceans imply a colder world leading to a build-up of snow and ice at the poles and in major mountain glaciers. By 400 A.D., however, temperatures had warmed enough to raise water levels to about three feet above current elevations. The ancient harbors of Rome and Ravenna from the time of the Roman Empire are now located about one kilometer from the sea. Evidence exists for a peak in ocean heights in the fourth century for points as remote as Brazil, Ceylon, Crete, England, and the Netherlands, indicating a world-wide warming.

Changes in the climate in Eurasia appear to have played a major role in the waves of conquering horsemen who rode out of the plains of central Asia into China and Europe. Near the end of the Roman Empire, around 300 A.D., the climate began to warm and conditions in central Asia improved apparently leading to a population explosion. These people, needing room to expand and a way to make a living, invaded the more civilized societies of China and the West. The medieval warmth from around 1000 A.D. to 1300 also seems to have also triggered an expansion from that area. During this second optimum period, the homeland of the Khazars centered around the Caspian Sea enjoyed much greater rainfall than earlier or than it does now. The increased prosperity in this area produced a rapidly rising number of young men that provided the manpower for Genghis Khan to invade China and India and to terrorize Russia and the Middle East.

After 550 A.D. until around 800, Europe suffered through a colder, wetter, and more stormy period. As the weather became wetter, peat bogs formed in northern areas. The population abandoned many lakeside dwellings while mountain passes became choked with ice and snow, making transportation between northern Europe and the south difficult. The Mediterranean littoral and North Africa dried up, although they remained moister than now.

Inhabitants of the British Isles between the seventh and the ninth centuries were often crippled with arthritis while their predecessors during the warmer Bronze Age period suffered little from such an affliction. Although some archaeologists have attributed the difficulties of the dark age people to harder work, the cold wet climate between 600 and 1000 A.D. may have fostered such ailments.

During the centuries after the fall of the Roman empire and with the deterioration of the climate, Greece languished. In 542 A.D., the population was decimated by the plague, aggravated by cold damp conditions; the Black Death struck again between 744 and 747. As a consequence the number of people was sharply reduced. Greece was partially re-populated in the ninth and tenth centuries when the Byzantine Emperors brought Greek settlers from Asia Minor back into the area. For the first time in centuries Greek commerce and prosperity returned -- probably due to an improved climate.

In the ninth century, land hunger and a rising population in Norway and Sweden spurred the Scandinavians on to loot and pillage by sea. Their first descent was on the monastery of Lindisfarne in northern England in 793. This was followed by raids on Seville in Muslim Spain in 844 and later farther into the Mediterranean. In 870 they discovered Iceland and in the next century, Greenland. In 877 they began an invasion of England and conquered from the north to the whole of the midlands -- all of which became a Danish overseas kingdom by the mid-tenth century. At the same time, they stormed France and the king had to cede them Normandy as a fief. They also crossed the Baltic (known as Rus in that time) and sent traders south to Islam and Byzantium.

The High Middle Ages and Medieval Warmth

From around 800 A.D. to 1200 or 1300, the globe warmed considerably and civilization prospered. This Little Climate Optimum generally displays, although less distinctly, many of the same characteristics as the first climate optimum. Virtually all of northern Europe, the British Isles, Scandinavia, Greenland, and Iceland were considerably warmer than at present. The Mediterranean, the Near East, and North Africa, including the Sahara, received more rainfall than they do today. North America enjoyed better weather during most of this period. China during the early part of this epoch experienced higher temperatures and a more clement climate. From Western Europe to China, East Asia, India, and the Americas, mankind flourished as never before.

Evidence for the medieval warming comes from contemporaneous reports on weather conditions, from oxygen isotope measurements taken from the Greenland ice, from upper tree lines in Europe, and from sea level changes. These all point to a more benign, warmer, climate with more rainfall but because of more evaporation less standing water. Not only did northern Europe enjoy more rainfall but the Mediterranean littoral was wetter. An early twelfth century bridge with twelve arches which still exists over the river Oreto at Palermo exceeds the needs of the small trickle of water that flows there now. According to Arab geographers two rivers in Sicily that are too small for boats were navigable during this period. In England at the same time, medieval water mills on streams that today carry too little water to turn them attest to greater rainfall. Although England apparently received more rainfall than in modern times, the warm weather led to more drying out of the land. Support for a more temperate climate in central Europe comes from the period in which German colonists founded villages. As average temperatures rose people established towns at higher elevations. Early settlements were under 650 feet in altitude; those from a later period were between 1,000 and 1,300 feet high; and those built after 1,100 were located above 1,300 feet.

H. H. Lamb counted manuscript reports of flooding and wet years in Italy. He discovered that starting in the latter part of the tenth century, the number of wet years climbed steadily, reaching a peak around 1300. Over the same period northern Europe was enjoying warmer and more clement weather. Not only was the temperature higher than now in Europe during the twelfth and thirteenth century but the population enjoyed mild wet winters. In the Mediterranean it was moist as well with summer thunderstorms frequently reported.

Studies have shown that some areas became drier during these centuries. In particular, the Caspian Sea was apparently four meters -- over 13 feet -- lower from the ninth through the eleventh century than currently. After 1200 A.D. the elevation of the lake rose sharply for the next two or three hundred years. In the Asian steppes, warm periods with fine summers and often little snow in the winter produced lake levels that were low by modern standards. A recent study of tree rings in California's Sierra Nevada and Patagonia concluded that the "Golden State" suffered from extreme droughts from around 900 to 1100 and again from 1210 to 1350 while the tip of South America during the first 200 years also enjoyed little precipitation.

The timing of the medieval warm spell, which lasted no more than 300 years, was not synchronous around the globe. For much of North America, for Greenland and in Russia, the climate was warmer between 950 and 1200. The warmest period in Europe appears to have been later, roughly between 1150 and 1300, although parts of the tenth century were quite warm. Evidence from New Zealand indicates peak temperatures from 1200 to 1400. Data on the Far East is meager but mixed. Judging from the number of severe winters reported by century in China, the climate was somewhat warmer than normal in the ninth, tenth, and eleventh centuries, cold in the twelfth and thirteenth and very cold in the fourteenth. Chinese scholar Chu Ko-chen reports that the eighth and ninth centuries were warmer and received more rainfall, but that the climate deteriorated significantly in the twelfth century. He found records, however, that show that the first half of the thirteenth century was quite clement and very cold weather returned in the fourteenth century. Another historian found on the basis of records of major floods and droughts that between the ninth and eleventh century China suffered much fewer of these calamities than during the fourteenth through the seventeenth. The evidence for Japan is based on records of the average April day on which the cherry trees bloomed in the royal gardens in Kyoto. From this record, the tenth century springs were warmer than normal; in the eleventh century they were cooler; the twelfth century experienced the latest springs; the thirteenth century was average and then the fourteenth was again colder than normal. This record suggests that the Little Climate Optimum began in Asia in the eighth or ninth centuries and continued into the eleventh. The warm climate moved west, reaching Russia and central Asia in the tenth through the eleventh, and Europe from the twelfth to the fourteenth. Some climatologists have theorized that the Mini Ice Age also started in the Far East in the twelfth century and spread westward reaching Europe in the fourteenth.

Europe

The warm period coincided with an upsurge of population almost everywhere, but the best numbers are for Europe. For centuries during the cold damp "dark ages" the population of Europe had been relatively stagnant. Towns shrank to a few houses clustered behind city walls. Although we lack census data, the figures from Western Europe after the climate improved show that cities grew in size; new towns were founded; and colonists moved into relatively unpopulated areas.

Historians have failed to agree on why after the eleventh century, the population soared. It might be more enlightening to ask why the population remained stagnant for so long. As John Keegan, the eminent military historian put it: "The mysterious revival of trade between 1100 and 1300, itself perhaps due to an equally mysterious rise in the European population from about 40,000,000 to about 60,000,000, in turn revived the life of towns, which through the growth of a money economy won the funds to protect themselves from dangers beyond the walls".

Although it is impossible to document it, the change in the climate from a cold, wet one to a warm, drier climate -- it had more rainfall, but more evaporation reduced bogs and marshy areas -- seems likely to have played a significant role. In the eighth through the eleventh centuries, most people spent considerable time in dank hovels avoiding the inclement weather. These conditions were ripe for the spread of disease. Tuberculosis, malaria, influenza, and pneumonia undoubtedly took many small children and the elderly -- those over 30.

Written records confirm that the warmer climate brought drier and consequently healthier conditions to much of Europe. Robert Bartlett, citing H.E. Hallam in Settlement and Society, quotes the people of Holland who invaded Lincolnshire in 1189 that "because their own marsh had dried up, they converted them into good and fertile ploughland." Moreover, prior to the twelfth century German settlers on the east side of the Elbe frequently named their towns with mar, which meant marsh, but later colonists did not use that suffix. Bartlett's explanation is that the term had gone out of use, but an alternative one is that the warmer climate had dried up the marshes.

With a more pleasant climate people spent longer periods outdoors; food supplies were more reliable. Even the homes of the peasants would have become warmer and less damp. The draining or drying up of marshes and wetlands reduced the breeding grounds for mosquitoes that brought malaria. In all the infant and childhood mortality rate must have fallen spawning an explosion in population.

From the ninth century, with a climate still quite cool, to the eleventh, medieval Europe was almost totally agricultural. The few cities that existed consisted mainly of religious seats with their support personnel. Even as late as the twelfth century, city dwellers made up less than 10 percent of the population. Trade before the eleventh century was virtually non-existent. People were tied to the land through custom and necessity. The great feudal estates grew what they ate and ate what they grew; they wove their own cloth and sewed their own clothes; they built what little furniture was needed. In a word they were almost entirely self-sufficient. The serfs that tilled the land had inherited rights to enough land to sustain a family. Typically the older son would follow his father. Any other sons either joined the priesthood, became monks, vagabonds, or in later centuries, mercenaries. Given the cold climate before the eleventh century, the lack of medical care, and a restricted diet fostering poor nutrition, few babies lived to adulthood. The problem of an excess of labor was, therefore, nonexistent. The truth is that the population was growing so slowly that a labor shortage persisted and the feudal nobility established laws prohibiting serfs from leaving their land.

Until the twelfth century when the weather became significantly more benign, a Europe fettered by tradition remained cloistered in self-sufficient units. The next two centuries, however, witnessed a profound revolution which, by the end of the fourteenth century, transformed the landscape into an economy filled with merchants, vibrant towns and great fairs. Crop failures became less frequent; new territories were brought under control. With a more clement climate and a more reliable food supply, the population mushroomed. Even with the additional arable land permitted by a warmer climate, the expansion in the number of mouths exceeded farm output: food prices rose while real wages fell. Farmers, however, did well with more ground under cultivation and low wages payable to farm hands.

The rise in the population may have contributed to the spread of primogeniture. Prior to the twelfth century, infant and child mortality coupled with short life expectancy required parents to be flexible in designating their heirs. Robert Bartlett quotes an estimate for the eleventh century that the probability of a couple raising sons to adulthood was only 60 percent.

Although the first sons born on the estates could follow their fathers, other children, especially the men, had to find new opportunities. The crusades furnished an occasion for both the sons of serfs and of the nobility to enrich themselves and even to find new land to cultivate. Others moved to virgin territory in eastern Europe, Scandinavia or previously forested or swampy areas. The Franks and Normans launched invasions of England, southern Italy, Byzantine Greece, and the eastern Mediterranean. In 1130 the Tancred de Hauteville clan, a notable example, founded the Kingdom of Sicily. This family, a classic case of an "over-breeding, land-hungry lesser nobility," consisted of 12 sons from two mothers who, recognizing that their Norman property was inadequate, invaded southern Italy in search of land and riches.

During the High Middle Ages, the Germans advanced across the Elbe to take land from pagan Serbs. The spread of knights and soldiers out of France and Germany demonstrates that the population was multiplying more rapidly in northern Europe than in southern. The rapid rise in numbers north of the Alps fits the improved climate scenario: global or continental warming brought greater temperature change and more beneficial weather to higher latitudes.

The more skilled and enterprising who did not seek their fortune in foreign lands typically flocked to towns and urban centers, becoming laborers, artisans, or traders. Both those who moved to the new cities and those who founded colonies were legally freed of feudal obligations. This new liberty, making risk taking and innovation possible, was essential for those in commerce.

The warmth of the Little Climate Optimum made territory farther north cultivable. In Scandinavia, Iceland, Scotland, and the high country of England and Wales, farming became common in regions which neither before nor since have yielded crops reliably. In Iceland, oats and barley were cultivated. In Norway, farmers were planting further north and higher up hillsides than at any time for centuries. Greenland was 4deg. to 7deg.F warmer than at present and settlers could bury their dead in ground which is now permanently frozen. Scotland flourished during this warm period with increased prosperity and construction. Greater crop production meant that more people could be fed, and the population of Scandinavia exploded. The rapid growth in numbers in turn propelled and sustained the Viking explorations and led to the foundation of colonies in Iceland and Greenland.

The increasingly warm climate was reflected in a rising sea level. People were driven out of the low lands and there was a large scale migration of men and women from these areas to places east of the Elbe, into Wales, Ireland, and Scotland. Flemish dikes to hold back the sea date at least from the early eleventh century. Although Pirenna and Bartlett attribute them to attempts to reclaim land from the sea to provide new areas for farming, the evidence points towards a higher water level that farmers in the low countries had to battle.[128] The earliest texts setting out rights on the reclaimed land fail to mention any obligation to maintain the dikes, although later ones spell out the requirement, suggesting that the problem of holding back the sea became worse over time. Robert Bartlett quotes from a Welsh chronicle on the influx of people from Flanders:

that folk, as is said, had come from Flanders, their land, which is situated close to the sea of the Britons, because the sea had taken and overwhelmed their land ... after they had failed to find a place to live in -- for the sea had overflowed the coast lands, and the mountains [sic] were full of people so that it was not possible for everyone to live together there because of the multitude of the people and the smallness of the land...

In addition to the land north of the Alps, the warm rainier climate benefited southern Europe, especially Greece, Sicily and southern Italy. All of the Mezzogiorno in the Middle Ages did well. Nicolas Cheetham, a former British diplomat who authored a recent book on Mediaeval Greece, reports that during the first half of the thirteenth century, the plains and valleys of the Peloponnese were fertile and planted with a wide variety of valuable crops and trees. They produced wheat, olives, fruits, honey, cochineal for dyeing, flax for the linen industry and, silk from the mulberry trees. The wealthy in Constantinople prized highly the wines, olives, and fruit from Greece. Thessaly's grain fed the Byzantine Empire. Patras exported textiles and silk of very high quality. Extensive forests, which were full of game, supplied acorns for hordes of pigs. Herders raised sheep and goats in the mountain pastures, while in the valleys farmers kept horses and cattle.

The Mediterranean flourished in the twelfth century. Christian and Moslem lands achieved great brilliance. Cordova, Palermo, Constantinople and Cairo all thrived, engendering great tolerance for contending religions. Christian communities survived and prospered in Moslem Cairo and Cordova. The Rulers of Byzantine countenanced the Moslems and often preferred them to "barbaric" Westerners.

In the West, Charlemagne, creator of the Holy Roman Empire, may have inaugurated the era of the High Middle Ages while Dante, writing The Divine Comedy, may have closed it. In A History of Knowledge, Charles Van Doren contended that: "the ... three centuries, from about 1000 to about 1300, became one of the most optimistic, prosperous, and progressive periods in European history." All across Europe, the population went on an unparalleled building spree erecting at huge cost spectacular cathedrals and public edifices. Byzantine churches gave way to Romanesque, to be replaced in the twelfth century by Gothic cathedrals. During this period construction began on the Abbey of Mont-St-Michel (1017), St. Marks in Venice (1043), Westminster Abbey in London (1045), the Cathedral of our Lady in Coutances (1056), the Leaning Tower at Pisa (1067), the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela in northern Spain (1078), the Cathedral of Modena (1099), Vézelay Abbey in France (1130), Notre-Dame in Paris (1163), Canterbury in England (1175), Chartres (1194), Rouen's cathedral in France (1201), Burgos' cathedral in Castile (1220), the basilica of Saint Francis in Assisi (1228), the Sainte Chapelle in Paris (1246), Cologne Cathedral (1248) and the Duomo in Florence (1298). Virtually all the magnificent religious edifices that we visit in awe today were started by the optimistic populations of the eleventh through the thirteenth centuries, although many were not finished for centuries. In southern Spain, the Moors laid the cornerstone in 1248 for perhaps the world's most beautiful fortress, the Alhambra. The Franks founded Mistra near ancient Sparta in the middle of the thirteenth century.

It took a prosperous society to launch such major architectural projects. In Europe, building the cathedrals required a large and mostly experienced pool of labor. During the week of June 23 to June 29, 1253, the accounts of the construction at Westminister Abbey, for example, showed 428 men on the job, including 53 stonecutters, 49 monumental masons, 28 carpenters, 14 glassmakers, 4 roofers, and 220 simple laborers.[135] Nearly half of all workers were skilled specialists. Even during the slowest season in November, the Abbey employed 100 workers, including 34 stonecutters. Masons and stonecutters earned the highest wages and usually hired a number of workers as assistants. Master craftsmen moved from job to job around Europe without any concern about national borders -- the first truly European Community. Historians have found than only 5 to 10 percent of the masons and stonecutters were local people, but 85 percent of the men who quarried the stones -- an unhealthy and arduous job -- were from the vicinity. Thus during these centuries a European-wide market flourished in skilled craftsmen.

Economic activity blossomed throughout the continent. Banking, insurance, and finance developed; a money economy became well established; manufacturing of textiles expanded to levels never seen before. Farmers were clearing forests, draining swamps and expanding food production to new areas. The building spree mentioned above was made possible by low wages resulting from a population explosion and by the riches that the new merchant classes were creating. In England, virtually all of the churches and chapels which had originally been built of wood were reconstructed in stone between the twelfth and fourteenth centuries. With the clergy still opposing buying and selling for gain, those who became wealthy often constructed churches or willed their estate or much of it to religious institutions as acts of redemption. They supplied much of the funds to erect the great Gothic cathedrals.

Starting in the eleventh century European traders developed great fairs that brought together merchants from all over Europe. At their peak in the thirteenth century they were located on all the main trade routes and served not only to facilitate the buying and selling of all types of goods but also functioned as major money markets and clearing houses for financial transactions. The fourteenth century saw the waning of these enterprises probably because the weather became so unreliable and poor that transport to and from these locations with great stocks of goods became impractical. Belgian historian Henri Pirenne attributes their decline to war, which may indeed have played a role, but the failure of crops and the increased wetness must have made travel considerably more difficult. Wet roads were muddy rendering it arduous to transport heavy goods. Crop failures made for famines and more vagabonds who preyed on travelers.

During the High Middle Ages, technology grew rapidly. New techniques expanded the use of the water mill, the windmill, and coal for energy and heat. Sailing improved through the invention of the lateen sail, the sternpost rudder and the compass. Governments constructed roads and contractors developed new techniques for use of stone in construction. New iron casting techniques led to better tools and weapons. The textile industry began employing wool, linen, cotton, and silk and, in the thirteenth century, developed the spinning wheel. Soap, an essential for hygiene, came into use in the twelfth century. Mining, which had declined since the Romans, at least partly because the cold and snow made access to mountain areas difficult, revived after the tenth century.

Farmers and peasants in medieval England launched a thriving wine industry south of Manchester. Good wines demand warm springs free of frosts, substantial summer warmth and sunshine without too much rain, and sunny days in the fall. Winters cannot be too cold -- not below zero Fahrenheit for any significant period. The northern limit for grapes during the Middle Ages was about 300 miles above the current commercial wine areas in France and Germany. These wines were not simply marginal supplies, but of sufficient quality and quantity that, after the Norman conquest, the French monarchy tried to prohibit British wine production. Based on average and extreme temperatures in the most northern current wine growing regions of France and Germany compared to current temperatures in the former wine growing regions in England, Lamb calculates that the climate in springs and summers were somewhere between 0.9 and 3.4 degrees Fahrenheit warmer in the Middle Ages.

Not only did the British produce wines during the Little Climate Optimum but farmers grew grapes in East Prussia, Tilsit, and south Norway. Many areas cultivated in Europe were much further up mountains than is possible under the modern climate. Together these factors suggest that the temperatures in central Europe were about 1.8deg. to 2.5deg.F higher than during the twentieth century.

Europe's riches and a surplus of labor enabled and emboldened its rulers to take on the conquest of the Holy Land through a series of Crusades starting in 1096 and ending in 1291. The Crusades, stimulated at least in part by a mushrooming population and an economic surplus large enough to spare men to invade the Muslim empire, captured Jerusalem in 1099 -- a feat not equaled until the nineteenth century. A major attraction of the first crusade was the promise of land in a "southern climate."

Even southern Europe around the Mediterranean enjoyed a more moist climate than currently. In the reign of the Byzantine Emperor Manuel I Comnenus, art and culture flourished and all the world looked to Constantinople as its leader. Under the control of the Fatimid caliphate, Egypt cultivated a "House of Science," where scholars worked on optics, compiled an encyclopedia of natural history, with a depiction of the first known windmills, and described the circulation of the blood. In Egypt block-printing appeared for the first time in the West. The caliphate turned Cairo into a brilliant center of Moslem culture. In Persia, Omar Khayyam published astronomical tables, a revision of the Muslim calendar, a treatise on algebra and his famous Rubáiyát.

As European commerce expanded, traders reached the Middle East, bringing back not only exotic goods, but new ideas and information about classical times. Drawing on fresh information about Aristotelian logic, St. Thomas Aquinas defined medieval Christian doctrine in his Summa Theologica. Possibly the oldest continuous university in the world was founded in Bologna for the study of the law in 1000 A.D. Early in the twelfth century a group of scholars under a license granted by the chancellor of Notre-Dame began to teach logic, thus inaugurating the University of Paris. Cambridge University traces its foundation to 1209 and Oxford to slightly later in the thirteenth century. Roger Bacon, one of the first to put forward the importance of experimentation and careful research, studied and taught at Oxford in the thirteenth century.

Secular writing began to appear throughout northern Europe. In the twelfth century the medieval epic of chivalry, the Chanson de Roland, was put into writing. Between 1200 and 1220 an anonymous French poet composed the delightful and optimistic masterpiece, Aucassin et Nicolette. An anonymous Austrian wrote in Middle High German the Nibelungenlied.

The Arctic

From the ninth through the thirteenth centuries agriculture spread into northern Europe and Russia where it had been too cold to produce food before. In the Far East, Chinese and Japanese farmers migrated north into Manchuria, the Amur Valley and northern Japan. As mentioned above, the Vikings founded colonies in Iceland and Greenland, a region that may have been more green than historians have claimed. It was also during this period that Scandinavian seafarers discovered "Vinland" -- somewhere along the East Coast of North America. The subsequent Mini Ice Age cut off the colonies in Greenland from Europe, and they eventually died off. Even today, during this warm period of the late twentieth century, the British climate forecloses large-scale grape production and Greenland is unsuitable for farming.

The Eskimos apparently expanded throughout the Arctic area during the medieval warm epoch. Starting with Ellesmere Land around 900 A.D., Eskimo bands and their culture spread from the Bering Sea into the Siberian Arctic. Two centuries later, these people migrated along the coast of Alaska and into Greenland. During this period the Eskimos' main source of food came from whaling, which had to be abandoned with the subsequent cooling. The Mini Ice Age forced the Thule Eskimos south out of northern Alaska and Greenland. These hardy aborigines had abandoned Ellesmere Land by the sixteenth century.

At the same time that the Eskimos were moving north, Viking explorers were venturing into Greenland, Vinland, and even the Canadian Arctic. Scandinavian sailors found Iceland in 860, Greenland around 930, and reached the shores of North America by 986. By the turn of the millennium, when the waters south-west of Greenland may have been at least 7deg.F warmers than now, Vikings were regularly visiting Vinland for timber. They were received with great hostility by the natives and eventually abandoned contact, although the last trip may have occurred as late as 1347, when a Greenland ship was blown off course. At the height of the warm period, Greenlanders were growing corn and a few cultivated grain. Some archaeologists have found evidence that Vikings from Greenland may have visited remote portions of the Canadian archipelago and even may have sailed through the Northwest Passage to the West Coat of America traveling as far south as the Gulf of California. At least one scientists believes that this visit is the origin of the Aztec belief in the visit of "fair" people from the East.

The Far East

As noted above, the warming in the Far East seems to have preceded that in Europe by about two centuries. Chinese Economist Kang Chao has studied the economic performance of China since 200 B.C. In his careful investigation, he discovers that real earnings rose from the Han period (206 B.C. to 220 A.D.) to a peak during the Northern Sung Dynasty (961 A.D. to 1127). This coincides with other evidence of longer growing seasons and a warmer climate. He explains the fall in worker productivity after the twelfth century as stemming from population pressures, but a change in climate may have played a significant role. Chao reports that the number of major floods averaged fewer than 4 per century in the warm period of the ninth through the eleventh centuries while the average number was more than double that figure in the fourteenth through the seventeenth centuries of the Mini Ice Age. Not only floods but droughts were less common during the warm period. The era of benign climate sustained about 3 major droughts per century, while during the later cold period, China suffered from almost 13 each hundred years.

The wealth of this period gave rise to a great flowering of art, writing, and science. The Little Climate Optimum witnessed the highest rate of technological advance in Chinese history. During the 300 years of the Sung Dynasty, farmers invented 35 major farm implements -- that is, over 11 per century, a significantly higher rate of invention than in any other era. In the middle of the eleventh century, the Chinese invented movable type employing clay pieces.

During the Northern Sung Dynasty Chinese landscape painting with its exquisite detail and color reached a peak never again matched. Adam Kessler, curator of the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History dates the earliest Chinese blue-and-white porcelain to the twelfth century. The Southern Sung produced pottery and porcelains unequaled in subtlety and sophistication. Literature, history and scholarship flourished as well. Scholars prepared two great encyclopedias, compiled a history of China, and composed essays and poems. Mathematicians developed the properties of the circle. Astronomers devised a number of technological improvements to increase the accuracy of measuring the stars and the year.

Japan also prospered during the Little Climate Optimum. In the Heian Period (794 A.D. to 1192) the arts thrived as emperors and empresses commissioned vast numbers of Buddhist temples. Murasaki Shikibu, perhaps the world's first female novelist, composed Japan's most famous book, The Tale of Genji. Other classical writers penned essays: Sei Shonagon -- another court lady -- wrote Makura-no-Soshi (the Pillow Book). The Japanese aristocracy vied in composing the best poems. All of this attests a prosperous economy with ample food stocks to support a leisured and cultivated upper class.

Over the four hundred years between 800 A.D. and 1200, the peoples of the Indian subcontinent prospered as well. Society was rich enough to produce colossal and impressive temples, beautiful sculpture, elaborate carvings, many of which survive to this day. The Lingaraja Temple, one of the finest Hindu shrines, as well as the Shiva Temple date from this period. Seafaring empires existed in Java and Sumatra, which reached its height around 1180. Ninth century Java erected the vast stupa of Borobudur; other temples -- the Medut, Pawon, Kelasan and Prambanan -- originate in this era. In the early twelfth century, the predecessors of the Cambodians, the Khmers, built the magnificent temple of Angkor Wat. In the eleventh century Burmese civilization reached a pinnacle. In or around its capital, Pagan, between 931 and 1284, succeeding kings competed in constructing vast numbers of sacred monuments and even a library. Today the area is a dusty plain littered with the crumbling remains of about 13,000 temples and pagodas, built in a more hospitable era.

Archaeologists studying the compositions of forests in New Zealand have found that the South Island enjoyed a warmer climate between 700 A.D. and 1400, about the time when Polynesians were colonizing the South Pacific Islands and the Maoris were settling in New Zealand. Partially confirming that warming are data from Tasmania of tree rings which show a warm period from 940 to 1000 and another from 1100 to 1190.

The Americas

Less is known about civilizations in the Americas during the Little Climate Optimum or even how the prevailing weather changed. Much of the currently arid areas of North America were apparently wetter during this epoch. The Great Plains areas east of the Rocky Mountains, the upper Mississippi Valley and the Southwest received more rainfall between 800 A.D. and 1200 than they do now. Radiocarbon dating of tree rings indicates that warmth extended from New Mexico to northern Canada. In Canada, forests extended about sixty miles north of their current limit.

Starting around 800 to 900 A.D., the indigenous peoples of North America extended their agriculture northward up the Mississippi, Missouri, and Illinois river basins. By 1000 they were farming in southwestern and western Wisconsin and eastern Minnesota. They grew corn in northwestern Iowa prior to 1200 in an area which is now marginal for rainfall. Indian settlements on the northern plains of Iowa were abandoned with colder drier weather that set in after 1150 to 1200. After that time, the natives substituted bison hunting for growing crops. In general the land east of the Rocky Mountains enjoyed wetter conditions from 700 to 1200 and then turned drier as it experienced greater intrusions of colder Arctic weather.

The Anasazi civilization of Mesa Verde flourished during the warm period, but the cooling of the climate at the end of the medieval warmth around 1280 probably led to its disappearance. This climatic shift brought drier conditions to much of the region, leading to a retreat from the territory and forcing the Pueblo Indians to shift their farming to the edge of the Rio Grande River.

Around 900, the Chimu Indians in South America developed an extensive irrigation system on Peru's coast to feed their capital of between 100,000 to 200,000 souls -- a huge number for the era. The Toltec civilization, which occupied much of Mexico, reached its apogee in the thirteenth century. By 1200, the Aztecs had built the pyramid of Quetzalcoatl near modern Mexico City. The Mayas' civilization, however, reached a peak somewhat earlier, before 1000, and declined subsequently for reasons that remain unclear. It is possible that the warming after 1000 led to additional rainfall in the Yucatan, making the jungle too vigorous to restrain and causing a decline in farming, while at the same time improving agricultural conditions in the Mexican highlands and farther north into what is now the southwestern United States.

Thus warmer times brought benefits to most people and most regions, but not all. As is always the case with a climate shift, the changes benefited some while affecting other adversely. Change is disruptive; at the same time it produces new ideas and new ways of coping with the world. Nevertheless, for most of the known world, the Little Climate Optimum of the ninth through the thirteenth centuries brought significant benefits to the local populations. Compared with the subsequent cooling it was nirvana.

The Mini Ice Age

The Little Ice Age is even less well defined than the medieval warm period. Climatologists are generally agreed that, at least for Europe, North America, New Zealand and Greenland, temperatures fell after 1300 to around 1800 or 1850, although with many ups and downs. There was a cold period in the first decade of the fourteenth century, another around 1430 and again in 1560. The end of this period of increasingly harsh temperatures could have been as early as 1700, 1850 or even 1900 for Tasmania. The worst period for most of the world occurred between 1550 and 1700. One reasonable interpretation of the data is that the world has been cooling since around 4500 B.C. with a temporary upswing during the High Middle Ages.

Europe and Asia cooled substantially from around 1300 to 1850, especially after 1400, with temperatures falling some 2deg. to 4deg.F below those of the twentieth century. This indicates that temperatures may have dipped by as much as 9deg.F in the two hundred years from 1200 to 1400, a drop of about the same magnitude as the maximum rise forecast from a doubling of CO2. These frigid times did bring hardships, and as the chart shows world population growth slowed. For much of these centuries, famine and disease stalked Europe and Asia.

Glaciers in North America and northern Europe peaked between the late 1600s and 1730 to 1780. In the Alps these ice sheets reached their maximum between 1600 and 1650. The coldness came later below the equator where the glaciers reached their extreme between 1820 and 1850.

Oxygen isotope ratios from oak trees in Germany document a steady decline in average temperatures from 1350 to about 1800, with the exception of a few small upsurges and one strong temperature spike in the first half of the eighteenth century. Since late in the 19th century they confirm a recovery to much higher levels. Icelandic records of sea ice attest to an increase between 1200 and the middle of the fourteenth century and then, starting in the latter half of the sixteenth century, a marked upswing in ice which appears to have peaked around 1800. As H. H. Lamb points out, "in most parts of the world the extent of snow and ice on land and sea seems to have attained a maximum as great as, or in most cases greater than, at any time since the last major Ice Age."

The Little Ice Age, especially the century and a half between 1550 and 1700 -- the exact timing varied around the globe -- produced low temperatures throughout the year and considerable variation in weather from year to year and from decade to decade. It included some years that were exceptionally warm.[183] The polar cap expanded as did the circumpolar vortex, driving storms and the weather to lower latitudes. Although much of Europe experienced greater wetness than during the earlier warm epoch, this dampness was more the product of less evaporation due to the cold than an excess of precipitation.

The cooling after the High Middle Ages can be seen in the lowering of tree lines in the mountains of Europe, changes in oxygen isotope measurement, and advances of the glaciers and of sea ice. This cooling diminished the abundance and quality of wine production in France, Germany and Luxembourg as depicted in historical documents such as weather diaries and farm records. The ocean, which had reached relatively high levels both in the late Roman period and again during the High Middle Ages, fell to lower elevations in the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries. As a result of an expanded ice cap, the circumpolar vortex, which funnels weather around the globe, moved south and spawned increasingly cold and stormy weather in middle latitudes. With the exception of southern United States and central Asia, both of which enjoyed more rainfall, this brought a worsening of the climate and disasters to people almost everywhere. During the coldest period of the seventeenth century, snow fell in the high mountains of Ethiopia above 10,000 feet which today never see snow. The subtropical monsoon rains decreased and receded farther south causing droughts in East Asia and parts of Africa.

The expansion of the circumpolar vortex produced some of the greatest windstorms ever recorded in Europe. A terrible tempest destroyed the Spanish Armada in 1588. Fierce gales wracked Europe in December 1703 and on Christmas Day 1717. The contrast between the cold northern temperatures which moved south and the warm subtropical Atlantic undoubtedly generated a fierce jet stream. Although we lack any information, this may also, have enhanced tornado activity on the plains of the United States.

The reduced temperatures had the following general effects: (1) Arctic sea ice expanded in the Atlantic eventually cutting off Greenland; (2) glaciers advanced in Iceland, Norway, Greenland, and the Alps; (3) the upper tree line in North America and central Europe lowered; (4) enhanced wetness spawned bogs, marshes, lakes, and floods; (5) rivers and lakes froze more frequently; (6) the number and strength of storms, some of which were extraordinarily destructive, intensified sharply; (7) harvests failed engendering famine and higher prices for basic foods; (8) peasants abandoned farms that no longer enjoyed reliable weather; (9) disease for both animals and humans spread.

As early as 1250, floating ice from the East Greenland ice cap was hindering navigation between Iceland and Greenland. Over the next century and a half the prevalence of icebergs became worse and by 1410 sea travel between the two outposts of Scandinavia ceased. Based on the ratio of isotopes of oxygen in teeth of ancient Norsemen, researchers have estimated that the climate in Greenland cooled by about 3deg. Fahrenheit between 1100 and 1450. For about 350 years, from the third quarter of the fifteenth century to 1822, no ships found their way to Greenland and the local population perished.

The deteriorating climate in Europe was heralded by harvest failure in the last quarter of the thirteenth century. Compounding the insufficiency was a shift of land from farming, which because of the change in climate was more chancy, to enclosure and sheep rearing. Average yields, which were already low by modern standards, worsened after the middle of the thirteenth century. One of the first severe bouts of cold wet weather afflicted Europe from 1310 to 1319, leading to large scale crop failures. Food supplies deteriorated sharply generating famine for much of Europe in 1315-18 and again in 1321. Harvest deficits and hunger preceded the Black Death by 40 years. According to Lamb, for much of the continent, "the poor were reduced to eating dogs, cats and even children." This scanty food output contributed to a decline in population which was aggravated by disease. The history of many villages shows that they were abandoned before the beginning of the plague not afterwards. By 1327, the population in parts of England -- especially those later devastated by the plague -- had fallen by 67 percent. People poorly nourished were quickly carried off by disease. Between 1693 and 1700 in Scotland, seven out of the eight harvests failed and a larger percentage of the population starved than died in the Black Death of 1348-50.

In two terrible years, 1347 and 1348, famine struck northern Italy, followed by the Black Death, which decimated most of those not already carried away by lack of food. Bubonic plague spread across the Alps after 1348, killing in the next two years about one-third of northern Europe's people. Life expectancy fell by ten years in a little over a century: from 48 years in 1280 to 38 years in the years 1376 to 1400. Crops often failed; peasants abandoned many lands that had been cultivated during the earlier warm epoch. Between 1300 and 1600 the growing season shrank by three to five weeks with a catastrophic impact on farming. In Norway and Scotland, the population declined and villagers deserted many locales well before the plague reached those areas. The capitals of both Scotland and Norway moved south before both areas lost their autonomy.

The cooling after 1300 may also have contributed to the bubonic plague, the greatest disaster to ever befall Europe. The disease appears to have originated around 1333 in China, shortly after major rains and floods in 1332, which are reputed to have caused 7 million deaths, while disturbing wildlife and displacing plague-carrying rats. The Black Death then spread to central Asia around 1338-9, which, with the increased coldness, was also drying out. By 1348 rodents carrying fleas infested with bubonic plague had marched or been carried from the Crimea into Europe. Historians have estimated that as many as one-third of all the people in Europe died in the raging epidemic that swept the continent. This outburst of the plague, like a similar one in the sixth century, occurred during a period of increasing coolness, storminess, and wet periods, followed by dry hot ones. The unpleasant weather is likely to have confined people to their homes where they were more likely to be exposed to the fleas that carried the disease. In addition the inclement weather may have induced rats to take shelter in human buildings, exposing their inhabitants to the bacillus.

Not only did the cold facilitate the spread of the plague, but it caused much other human suffering. In July of 1789, just prior to the French Revolution, wet weather and air temperatures between 59 and 85 caused an ergot blight in the rye crop of Brittany and other parts of France. This blight caused hallucinations, paralysis, abortions and convulsions and came after a very cold winter that had created severe food shortages. Earlier in that century wet cold summers had produced two famine years in Europe.

The end of the medieval warmth had devastating effects on populations that lived at the edge of habitable lands. For example, historians have estimated the population of Iceland at the end of the eleventh century at about 77,000, and early in the fourteenth it still numbered over 72,000. By the end of the eighteenth century, after several hundred years of coolness and stormy weather, the number of Icelanders had been cut in half to 38,000.

The poorer climate in Europe after the thirteenth century brought a halt to the economic boom of the High Middle Ages. Innovation slowed sharply. Except for military advances, technological improvements ceased for the next 150 years. Population growth not only ended but, with starvation and the black death, fell. Without the drive of additional numbers of people, colonial enterprise ceased and no new lands were reclaimed nor towns founded. The economic slump of 1337 brought on the collapse of the great Italian bank, Scali, leading to one of the first recorded major financial crises. Construction on churches and cathedrals halted.

The hardships of the fourteenth century induced a search for scapegoats. In 1290 after some years of crop failures, the king of England expelled the Jewish population from the country. The French king followed this example in 1306 and again in 1393. In 1349, the Christians of Brabant massacred the local Jews and expelled the remainder twenty-one years later.

The Mini Ice Age at its coldest devastated the fishing industry. From 1570 to 1640, during the most severe period, Icelandic documents record an exceptionally high number of weeks with coastal sea ice. Except for a few years, fishermen from the Faeroe Islands suffered from a lack of cod from 1615 to 1828 -- cod needs water warmer than 36deg. Fahrenheit to flourish. During the worst periods, 1685 to 1704, fishing off south-west Iceland failed totally. In the very icy year of 1695, Norwegian fishermen found no cod off their coast. Lamb calculates that the sea around the Faeroe Islands was probably 7deg. to 9deg.F colder than it has been over the last century.

The Mini Ice Age brought hard times to Southern Europe as well. Severe winters and wet summers created shortages and famines in the south of France and in Spain. The great variability in the weather made agricultural output quite uncertain and contributed to a farming crisis in the Iberian Peninsula. Although one cannot know for sure that it was the weather, the whole of the Mediterranean littoral declined economically in the seventeenth century.

The cold had devastating effects elsewhere in the world. In China, frosts killed the orange trees in Kiangsi province between 1646 and 1676. Per capita incomes fell as food prices rose. As already mentioned, cooler weather brought an end to the Anastazi Indian pueblo culture, as well as ending native American farming in the upper middle west.

According to Nicolas Cheetham, in the second half of the thirteenth century warfare in Greece and the necessity of keeping a large military establishment under arms reduced its previous prosperity. War does exact a high toll on economies, but it seems extraordinarily coincidental that economic troubles occurred at the time Europe was experiencing a deteriorating climate. In 1268, the King of Naples, in gratitude for military service send wheat, barley and cattle to the Peloponnese. Was this needed because of crop failures solely due to military disruptions? Although not necessarily weather related, in 1275 Geoffroy de Briel, a major figure in medieval Greece, died during a military campaign of dysentery, a disease often exacerbated by cold wet conditions.

Notwithstanding the cooling climate and the ravages of disease after 1300, European civilization recovered with the advent of the Renaissance in the fifteenth century. This burst of cultural activity represented a continuation, an expansion, and a deepening of the artistic and intellectual activity of the High Middle Ages. Ironically, the outpouring of art, science and literature that made up the Renaissance may have been sustained by the plague. The colder climate made agriculture more chancy, reduced the territory available for farming, and cut yields. Yet without the one-third drop in Europe's population caused by the Black Death, food supplies would have been too meager to support a large artistic and cultured class that promoted and supported the arts. The reduced agricultural output, however, was still large enough to support the even more diminished population. In China, which experienced a slower decline in numbers, real wages fell and the people became increasingly impoverished. But in Europe, as a result of such a terrible death rate over a very short period, real incomes for the survivors actually climbed.

From around 1550 to 1700 the globe suffered from the coldest temperatures since the last Ice Age. Lamb estimates that in the 1590s and 1690s the average temperature was 3deg.F below the present. Grain prices increased sharply as crops failed. Famines were common. The Renaissance had ended; Europe was in turmoil. The Continent suffered from cold and rain, which produced poor growing conditions, food shortages, famines and finally riots in the years 1527-29, 1590-97, and the 1640s. The shortages between 1690 to 1700 killed millions and were followed by more famines in 1725 and 1816.

China, Japan, and the Indian subcontinent were also afflicted with severe winters between 1500 and 1850-80. Despite the development of a new type of rice that permitted the cultivation of three crops a year on the same land -- up from two -- the population of China, as well as that of Korea and the Near East, declined for two centuries after 1200, undoubtedly reflecting a deteriorating climate. The abandonment of sea trade by the Chinese most likely resulted from deteriorating weather and less population pressure.

Costs and Benefits of Efforts to Mitigate Warming

If mankind had to choose between a warmer or a cooler climate, humans, most other animals and, after adjustment, most plants would be better off with higher temperatures. Not all animals or plants would prosper under these conditions; many are adapted to the current weather and might have difficulty making the transition. Society might wish to help natural systems and various species adapt to warmer temperatures (or cooler, should that occur). Whether the climate will warm is far from certain; that it will change is unquestionable. The weather has changed in the past and will no doubt continue to vary in the future. Human activity is likely to play only a small and uncertain role in climate change. The burning of fossil fuel may generate an enhanced greenhouse effect or the release into the atmosphere of particulates may cause cooling. It may also be simply hubris to believe that Homo Sapiens can affect temperatures, rainfall and winds.

As noted, not all regions or all peoples benefit from a shift to a warmer climate. Some locales may become too dry or too wet; others may become too warm. Certain areas may be subject to high pressure systems which block storms and rains. Other parts may experience the reverse. On the whole, though, mankind should benefit from an upward tick in the thermometer. Warmer weather means longer growing seasons, more rainfall overall, and fewer and less violent storms. The optimal way to deal with potential climate change is not to strive to prevent it, a useless activity in any case, but to promote growth and prosperity so that people will have the resources to deal with any shift.

It is much easier for a rich country such as the United States to adapt to any long term shift in weather than it is for poor countries, most of which are considerably more dependent on agriculture than the rich industrial nations. Such populations lack the resources to aid their flora and fauna in adapting, and many of their farmers earn too little to survive a shift to new conditions. These agriculturally dependent societies could suffer real hardship if the climate shifts quickly. The best preventive would be a rise in incomes, which would diminish their dependence on agriculture. Higher earnings would provide them with the resources to adjust.

The cost of trimming emissions of CO2 could be quite high. William Cline of the Institute for International Economics -- a proponent of major regulatory initiatives to reduce the use of fossil fuels -- has calculated that the cost of cutting emissions from current levels by one-third by 2040 as 31/2 percent of World Gross Product. Given his assumption that cutbacks of CO2 emissions are done by the least cost methods and his bias, we can be certain that in the real world outlays to slow warming would be considerably higher. In terms of the estimated level of world output in 1992, his estimate would amount to roughly $900 billion annually, an amount that could slow growth and impoverish some who survive on the margin. These resources could be better spent on promoting investment and growth in the poorer countries of the world.

Should warming become apparent at some time in the future and should it create more difficulties than benefits, policy makers would have to consider preventive measures. Based on history, however, global warming is likely to be positive for most of mankind while the additional carbon, rain, and warmth should also promote plant growth that can sustain an expanding world population. Global change is inevitable; warmer is better; richer is healthier.

Debunking Soda Pop Gases Myths Pt.1 About CO2 Global Warming vs. Greenhouse Gases

Since increasing carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is causing global warming, then why the continued manufacture of Carbon Dioxide Fire Extinguisher and Carbonated Soft Drinks? Climate change deniers make many false claims about carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. These include the idea that CO2 has a limited or negligible impact on global warming—or even has the net effect of cooling our planet. Some also claim that the greenhouse effect would violate the laws of physics. Others make the assertion that the small quantities of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere couldn't possibly cause significant worldwide temperature changes. As I show here, every single one of these arguments are incorrect.

-

19:34

19:34

What If Everything You Were Taught Was A Lie?

1 day agoJihadi Grape Are Teenage UK Or American Girl Muslim Grooming Gangs Criminality Filthy Ideology

1.28K7 -

1:25:59

1:25:59

The Quartering

3 hours agoCandace Owens Assassination Plot, Fat Acceptance Is Over, James Comey Indictment Thrown Out

101K27 -

LIVE

LIVE

The HotSeat With Todd Spears

1 hour agoEP 214: Do YOU Believe In Miracles???

667 watching -

8:22

8:22

ChukesOutdoorAdventures

1 day ago $0.06 earnedMarlin 1894 Trapper in 10mm

3.46K2 -

![[Ep 798] What the Hell is in our Food? | Brotherhood of Terror | 2026 Economic Boom!](https://1a-1791.com/video/fwe2/f7/s8/1/C/a/S/C/CaSCz.0kob-small-Ep-798-What-the-Hell-is-in-.jpg) LIVE

LIVE

The Nunn Report - w/ Dan Nunn

1 hour ago[Ep 798] What the Hell is in our Food? | Brotherhood of Terror | 2026 Economic Boom!

263 watching -

21:09

21:09

Neil McCoy-Ward

1 hour ago🔥 SHOCK! As This 'UNEXPECTED' Move Has Left Western Leaders Scrambling!

7.09K3 -

1:17:25

1:17:25

TheSaltyCracker

2 hours agoSALTcast 11-24-25

34.3K51 -

7:51

7:51

Dr. Nick Zyrowski

6 days agoHow To Starve Fat Cells - Not Yourself!

54.2K6 -

1:11:53

1:11:53

DeVory Darkins

4 hours agoBREAKING: Hegseth drops NIGHTMARE NEWS For Mark Kelly with potential court martial

113K69 -

LIVE

LIVE

Dr Disrespect

6 hours ago🔴LIVE - DR DISRESPECT - ARC RAIDERS - BLUEPRINTS OR DEATH

2,036 watching