Premium Only Content

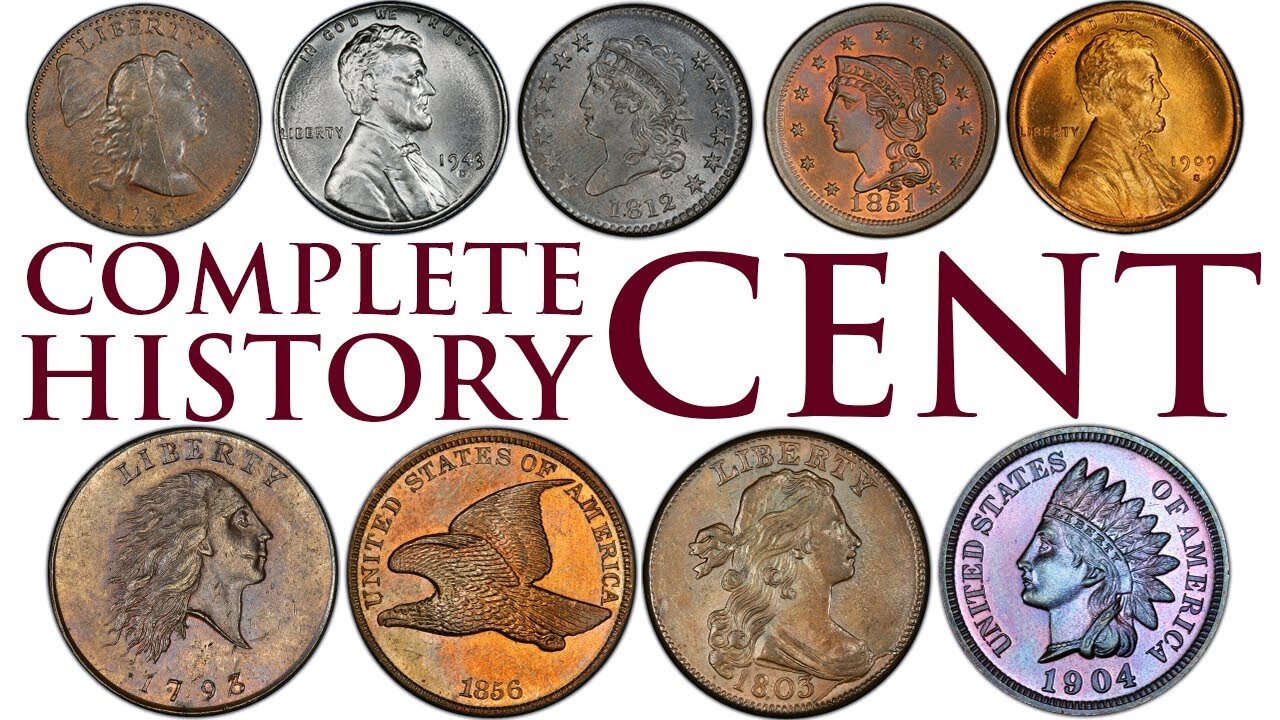

The Complete History of the United States Penny

Hi everyone, today I show you how the United States Penny was born. This humble coin goes back to the beginning of the USA and shoes no signs of stopping. Fugio Copper Cent (1787)

The first copper coins issued by the authority of the United States were the “Fugio” cents, struck in 1787 by a private mint. This coin was 100% copper and this composition would continue until the mid-1800's. Paul Revere, a noted blacksmith, supplied some of the copper for one-cent coins minted during the early 1790's. The legends of these coins have been credited back to Benjamin Franklin, and the coin, as a consequence, has sometimes been referred to as the "Franklin Cent,” but also has been called “Sun Dial,” “Ring,” and “Mind your business” cents.

A sundial is depicted on the obverse with the sun above it, and the Legends “Fugio,” which means “I Fly,” and “Mind Your Business,” is accompanied by the date 1787. The reverse features thirteen connected chain links to represent the original states, with the legend, “United States” and the motto, “We Are One.”

Flowing Hair Cent (1793)

Flowing Hair Cent (1793)

The U.S. Mint opened for full-time coin production in 1793, and the one-cent coin was among the very first coins struck at the U.S. Mint that year. The U.S. Mint produced its first circulating coins, the copper cents were minted in late February 1793, with over 11,000 copper cents delivered March 1, 1793. The first pennies struck at the U.S. Mint were made of pure copper and were much larger than the modern one-cent coins we are accustomed to using today. They are called Large cents, because they measured nearly the diameter of a modern half-dollar and were over five times heavier and almost 50% larger than its contemporary counterpart.

These first cents were hand engraved, a laborious and time-consuming process. The obverse shows a youthful bust of a wild-haired Liberty facing right with long flowing hair. The motto “Liberty” is above, with the date below. The reverse has a circular chain with 15 links representing the number of states in the union. Within the chain is the value “One Cent” and “1/100”. The legend “United Sates of America” is around the border.

Although, one variety the abbreviation “Ameri” is used due to poor spacing of the engraver, suspected to have been Chief Coiner, Henry Voigt. Chain Cents were not popular with the public. Some critics thought Liberty had unkempt hair and a frightened look in her eye, and that the chain links, that were meant to symbolize strength in unity, reminded some of the uncomfortable chains of slavery. Today, Chain cents are among the rarest and most beloved of all United States coins. The “Ameri” coin is a highly prized coin, because it’s considered the first variety struck by the Federal Government.

Many people associated the chain device with the chains of slavery. Besides the unpopularity of the Chain Cents, they were not especially attractive either, and did not wear well. Production stopped just after 36,103 pieces were minted. The design was quickly replaced with a similar Liberty bust on the obverse with some leaves of a plant below her, and on the reverse, the 15 chain links were replaced by a wreath surrounding the value of “One Cent” in the center, and the fractional value of “1/100” below the wreath. The Wreath Cent also has an inscription the edge reading “One Hundred For A Dollar.” From the summer of 1793 into the fall, Mint Director David Rittenhouse had the cents redesigned several times. The revised cent was most likely the work of Henry Voigt, and the Wreath Cents were produced from April to July of 1793.

Liberty Cap Cent (1793 – 1796)

Liberty Cap Cent (1793 – 1796)

The Liberty Cap large cents of 1793-1796 are the classics of early American copper coinage. They represent the third step in the infant Philadelphia Mint’s quest for a permanent cent design, succeeding the Chain and Wreath cents that began the new decimal coinage early in 1793. This version of the cent was from Henry Voigt’s talented colleague, Joseph Wright, who was a superb engraver. His Liberty design borrowed heavily from a medal conceived by Benjamin Franklin, and struck at the Paris Mint in 1783. The Libertas Americana medal was engraved by Augustin Dupres and it obverse left Liberty bust design, and had the Phrygian cap behind her head, which was worn by freed slaves in ancient times.

Joseph Wright and his wife succumbed to the effects of the almost annual “yellow fever” epidemics that plagued Philadelphia, in mid-September, 1793. Wright’s original Liberty Cap bust was revised in 1794 by a new engraver named Robert Scot, who was hired in November 1793. Scot was commissioned as the first Chief Engraver of the United States Mint in Philadelphia by Mint Director Rittenhouse, to replace the recently deceased Wright. Scot turned Liberty’s face from left to right, so it conformed to the portrait on the cents. The 1793 Liberty Head Large Cent employed a new technology, using a punch for Liberty’s head and cap. This allowed faster production and consistent appearance.

The large cent Liberty cap cent ran from 1793 to 1796, and had several revisions. In 1795, the legal weight of the large cent was reduced from 208 grains to 168 grams grains. The thickness of the planchet was reduced, which lost the lettering on the edge of the Large Cent.

Draped Bust Cent (1796 – 1807)

Draped Bust Cent (1796 – 1807)

At no other time in American history was the one cent coin as important as it was in the closing years of the 18th century. Although cumbersome, the large copper coins were useful for very small transactions, unlike the wide variety of foreign coins then in circulation. The Draped Bust large cent first appeared in mid-1796 as a replacement for the former Liberty Cap design. The "Draped Bust" design was the name given to a design of U.S. coins that appeared on much of the regular-issue copper and silver United States coinage from 1796 to 1807, designed by Mint Engraver, Robert Scot.

Scot’s new Draped Bust design was modeled after a drawing by artist Gilbert Stuart. It depicts Liberty with flowing hair, a ribbon behind her head and drapery at her neckline. The inscription LIBERTY is above the bust and the date below. The reverse features the denomination ONE CENT, encircled by an open wreath of two olive branches tied with a bow. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA surrounds the wreath, and the fraction 1/100 is between the ends of the bow.

There are three varieties of reverses; each varies the leaves and berries on the wreath. They are known as the “Type of 1794,” “Type of 1795” or “Type of 1797.” All three types were used on the reverse of 1796 cents, with the latter two types on the 1797. The last reverse remained constant on the dates through 1807. Over 16 million Draped Bust large cents were made between 1796 and 1807.

Classic Head Cent (1808 – 1814)

Classic Head Cent (1808 – 1814)

The Draped Bust design was replaced in 1808 with the introduction of the “Classic Head” motif by the new Second Engraver, John Reich. The new design was concurrent with an improvement in die steel allowing, for the first time, an unprecedented 300,000 impressions per working die. However, this series does not compare in sharpness and quality to the previous cent designs (1793 – 1807), or those struck later (1816 on). This was because the copper used was softer, having more metallic impurity, making this series difficult to find in choice condition.

Reich’s obverse design for the cent was a left-facing portrait of Liberty with curly hair, tied with a headband inscribed LIBERTY. Miss Liberty is surrounded by 13 stars, seven to the left and six to the right, with the date below her. The coin’s reverse carries the statement of value, ONE CENT, within a continuous wreath. This, in turn, is encircled by the inscription UNITED STATES OF AMERICA.

Production of the new design began in 1808, with just over one million pieces struck. A cent shortage developed the following year, however, when the Mint ran out of planchets. Production returned to normal in 1810, the experienced drastically reduced mintages. After a final low-mintage year in 1814, the abbreviated series came to an end. Combined total mintage for the series’ seven dates is just 4,757,722, all from the Philadelphia Mint.

In 1815, there was another shortage of copper planchets, so no one-cent coins were minted that year due to a copper shortage caused by the War of 1812 with Great Britain. This is the only year missing from U.S. cent coinage from 1793 to the present.

Coronet Head Cent (1816-1839)

Coronet Head Cent (1816 – 1839)

Since it struck its first coins in 1793, the U.S. Mint had been harshly criticized. As an institution it had become increasingly sensitive to public ridicule. Shortly after the Classic Head cent was introduced in 1808, critics pointed out that the fillet on Liberty’s head had not been worn by women in Classical times. The new Coronet design featured an enlarged head of Liberty. The fillet holding the hair on the previous Classic Head series was replaced by a coronet and the word LIBERTY was added in relief. The reverse was essentially unchanged and retained the “Christmas wreath” of the 1808 design. The “Coronet” type is also known as the “Matron Head.”

When new in 1816 the Coronet design represented the latest in mint technology and design, but by 1839 both design and manufacturing methods were overtaken by the advent of the steam powered coin press. New designs were the order of the day, and the old Coronet cent passed into the quaintness of a bygone era, replaced by Christian Gobrecht’s Braided Hair design. During the 24 years of the Coronet design (1816-1839), the Philadelphia Mint produced a total of 51,706,473 pieces.

Braided Hair Cent (1839 – 1857)

Braided Hair Cent (1839 – 1857)

By 1839, the large cent design fell out of favor as with previous issues, the large cent had suffered ridicule since its beginnings. The coin designs had nicknames describing Miss Liberty vividly to illustrate the public’s disdain. From the “Liberty in a fright” of the Chain cents, through the Classic Head’s “fat mistress,” to the “obese ward boss” of the Matron Head.

The last Large Cent, known as Braided Hair Cent, was minted from 1839-1857. Braided Hair coins achieved greater uniformity than any of the earlier large cents. Introduction of steam power, advances in hubbing the design into the dies and the use of logotypes or single, four-digit punches to impress dates streamlined the minting process.

The obverse is bust portrait of Liberty wearing a coronet, with the crown is inscribed with “Liberty”, surrounded by the traditional 13 stars, with the date below. The new cent was introduced in 1839, it was modified slightly in 1843, and continued in production until large copper cents were discontinued altogether in 1857. By the mid-1850s it was apparent to Mint officials that the large copper cents struck since 1793 were too cumbersome and unpopular, as well as increasingly uneconomical to make. The U.S. Mint gave serious thought to replacing the large cents with a smaller coin. In 1857, the Mint released a smaller Penny made of 12% nickel and 88% copper with a totally new Flying Eagle design.

Flying Eagle Cent (1856 – 1858)

Flying Eagle Cent (1856 - 1858)

As the value of the one-cent coin dropped, so did Americans’ tolerance of carrying around a bunch of heavy, large one-cent coins in their pockets and purses. As early as 1850, the Mint gave serious thought to replacing the large cents with a smaller coin and to drive out foreign coins like the Spanish Reales. In 1857, Congress directed the United States Mint to produce smaller one-cent coins made of both copper and nickel. While the large old pennies had been constructed of copper alone, these new pennies were each 88% copper and 12% nickel. The Mint Act of 1857 was signed February 21, abolished the copper half cent and large cent that had been minted since 1793. This was the first use of copper-nickel by the United States. The copper-nickel made them look brighter and they began to be called "White cent" or "Nicks".

This American penny features a flying eagle on one side, and a wreath on the other, earning it the name the “Flying Eagle cent.” Unlike older larger versions of the American penny, the Flying Eagle cent was about the same size as today’s coins. After 64 years, the old large cents were replaced by the Flying Eagle small cent, which were released to the public in exchange for old coppers and Spanish silver. On May 25th at 9 am the Mint doors opened to a crowd of over a thousand eager Philadelphians with their bags of small change, waiting their turn in their old coins in exchange for the shiny new issues. The demand was so great that many resold their new coins on the steps of the Mint for a profit within minutes of receiving them. Once the U.S. Mint began issuing the first of these small cents, there was real interest in collecting contemporary U.S. coinage, like the new Flying Eagle type cent and the older larger cents. Now there were only two coin grades, “new” and “used.” People became nostalgic for the big old pennies they had known from childhood, and these cents began disappearing from circulation, as collectors began to create date sets. Collectors began to gain an awareness of replacing an existing coin with a better one. From then to now, Flying Eagle Cents have proved enormously popular over the decades.

Designed by James B. Longacre, the Flying Eagle motif was actually an adaptation of the design used on pattern silver dollars twenty years before. The eagle figure had originally been drawn by Titian Peale and sculpted by Christian Gobrecht. The reverse wreath was similarly adapted from the model Longacre had made for the 1854 one and three dollar gold pieces.

Indian Head Cent (1859 – 1909)

Indian Head Cent (1859 – 1909)

The Indian cent was first introduced in 1859, and replaced the Flying Eagle penny, with a design that lasted for fifty years, spanning through 1909. Mint Director James Ross Snowden selected the Indian Head design, and Mint Chief Engraver, James Barton Longacre, designed the coin. The simplicity of the coin satisfied everyone. The Indian cent depicts an Indian princess, and a popular story about its design claims a visiting Indian chief lent the designer's daughter his headdress so she could pose as the Indian princess model. Also, when the coin was first produced, Longacre's initials did not appear on the coin, but in 1864, he added a small "L" on Liberty’s ribbon that remained on the ribbon through the end of the series in 1909.

The obverse bears the inscription, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, with an Indian head (Liberty) facing to the left, wearing a feather bonnet. The word LIBERTY is shown on the band across the bonnet, and shows the mint date at the bottom. The reverse side has ONE CENT within a laurel wreath for one year only in 1959. In 1860 the reverse design was changed slightly, replacing the laurel wreath with an oak wreath, with three arrows inserted under the ribbon that binds the two branches of the wreath. Above and between the ends of the branches is the shield of the United States.

The coins that were struck between 1859 and 1864 were a copper-nickel coin, composed of 88 percent copper and 12 percent nickel, as required by law. This copper-nickel alloy made the Indian cent a light color that led to its being called a “white” cent. Most Indian cents minted during the Civil War went primarily to pay Union soldiers. Because of War-related hoarding the Mint decided to switch to a cheaper bronze alloy. After the Civil War in 1864, the composition of the one-cent coin was changed to 95% copper and 5% zinc, and the weight was reduced by a third, from 72 grains to the present weight of 48 grains, resulting in a thinner coin much like the cent we know today.

The Indian Head Cent remained in use for half a century before giving way to the Lincoln cent in 1909. All issues were minted at the Philadelphia Mint, except for the last two years when the San Francisco Branch Mint struck India Head Pennies in 1908 and 1909. All in all, the total production of the Indian Head cent was 1,849,648,000 pieces. Despite being produced more than a century ago, this one-cent American penny is still relatively common, likely due to its post-Civil War popularity.

Lincoln Wheat Cent (1909 – 1958)

Lincoln Wheat Cent (1909 – 1958)

In 1909, the Indian Head American penny was discontinued in favor of the Lincoln penny, which commemorated the 100th birthday of President Abraham Lincoln. President Roosevelt considered Lincoln the savior of the Union, the greatest Republican President, and also he considered himself Lincoln's political heir. He hired designer, Victor David Brenner who was a Lithuanian immigrant and a friend of Roosevelt, who knew him as a skilled engraver and designer. Brenner paid the martyred president a lasting tribute, in the form of a sympathetic obverse portrait of Abraham Lincoln. The Lincoln Penny became commonly known as the “Wheat Penny” because the reverse featured two stalks of wheat on the reverse. The Wheat Cent design was coined until 1958 when the reverse was changed to the Memorial design. The Lincoln penny is now the longest-running design in United States Mint history. Abraham Lincoln was the first historical figure to grace a U.S. coin when he was portrayed on the one-cent coin to commemorate his 100th birthday. The Lincoln penny was also the first U.S. cent to include the words "In God We Trust."

Brenner’s obverse design featured a portrait of Lincoln facing right, and the motto IN GOD WE TRUST, for the first time on the cent. Flanking Lincoln’s bust on the left was the inscription LIBERTY, with the date on the right. The reverse design showed two sheaves of wheat, one on either side, framing the inscriptions ONE CENT, E PLURIBUS UNUM and UNITED STATES OF AMERICA.

Waiting for Lincoln Cents

The first Lincoln pennies prominently displayed the initials of the artist, “VDB” at the base of the reverse side. The 1909 VDB penny made its commercial debut on August 2, 1909. On that day, small boys, pint-sized entrepreneurs with pockets full of shiny new pennies, became impromptu street corner coin dealers.

They offered three new Lincoln pennies for a five cent nickel. However, there were massive public outcries that the “VDB” initials was a tasteless self-advertisement, which prompted the U.S. Mint to quickly remove the designer’s initials. Production was stopped with only 484,000 coins struck at the San Francisco mint. As a result, the Lincoln S-VDB penny is one of the rarest and most coveted coin in the series.

The Lincoln cent was an instant success from the day it was released. People lined up for city blocks just to get a couple examples from their local banks. In fact, Lincoln pennies were already selling for more than face value in the weeks immediately after their release, and there simply weren’t enough available from banks and the U.S. Mint to satisfy the demand!

Liberty Cap Cent (1793 – 1796)

Lincoln Steel Cent (1943)

In 1943, there was an urgent need for copper to make munitions for the war effort during World War II. That year the copper was removed from the penny and zinc-coated steel cents were made for the first and only time in history. The Philadelphia, Denver, and San Francisco mints each produced these 1943 Lincoln cents. Copper returned to the U.S. penny in 1944, and the Lincoln penny contained mostly copper until 1982.

The 1943 steel cent had a bright white chrome like appearance and had magnetic properties. It is the only regular-issue United States coin that can be picked up with a magnet. The steel cent was also the only coin issued by the United States for circulation that does not contain any copper. All other U.S. coins have some copper, even gold coins at various times contained from slightly over 2% copper to an eventual standardized 10% copper.

The 1943 cent was nicknamed “steelies,” these coins caused confusion because they closely resembled dimes; they also rusted and deteriorated quickly. The public soon complained that the new coins were becoming spotted and stained. As the 1943 steel pennies circulated, the zinc coating started to turn dark gray and almost black. If it was in circulation long enough, the zinc coating completely wore off, and the steel underneath would start to show through. When exposed to moisture the penny would start to rust. This was because zinc and iron form an electromagnetic "couple"; the two metals soon corrode when in contact with each other in a damp atmosphere.

In 1942, the U.S. Mint took all but a trace of tin out of the cent alloy, which technically changed the metal from bronze to brass. Because the Mint had a supply of existing (bronze) coining strip already prepared from the previous year, they accidentally made 1943 Lincoln pennies on bronze planchets. Today, 1943 Cents on Bronze Planchets rank among the most desirable and valuable of all Mint Errors. An estimated 40 examples are believed to have been struck, with approximately 12-15 examples are known to exist today. When 1943 Bronze Cents are auctioned, they sell for well over $1 million.

In an error similar to the 1943 cents, a few 1944 cents were struck on steel planchets left over from 1943. The 1944 steel cent was produced at all three mints. However, only 2 San Francisco-minted 1944-S Steel Cents are known to exist, making it rarest of the 1944 Steel Penny mints. Most experts believe that there are still a few yet to be discovered! The 1944 steel penny has just about as much interest swirling around it as does the 1943 copper cent. Both the 1943 copper Lincoln cent and 1944 steel Lincoln penny are worth an incredible amount of money because they’re so very rare.

Lincoln Memorial Cent (1959 – 2008)

Lincoln Memorial Cent (1959 – 2008)

1959 marked the 150th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s birth, and the 50th anniversary of the Lincoln cent. The U.S. The Mint celebrated these events by giving the cent a new reverse design depicting the Lincoln Memorial. The reverse was designed by Frank Gasparro, an assistant mint engraver at the time, who later became the Mint’s Chief Engraver.

On Sunday morning, December 21, 1958, President Eisenhower issued a press release announcing that a new reverse design for the cent would begin production on January 2, 1959. The redesign came as a complete surprise, as word of the proposal had not been leaked. The coin was officially released on February 12, 1959, the 150th anniversary of Lincoln's birth.

From 1959 until 1982 pennies were composed of 95% copper and 5% tin and zinc. However, the price of copper began rising, so the United States Treasury decided to change the composition of the Lincoln cent because the price of copper had simply gotten too expensive.

Copper prices began to rise in 1973, to such an extent that the intrinsic value of the coin approached a cent, and citizens began to hoard cents, hoping to realize a profit. The Mint decided to switch to an aluminum cent. Over a million and a half such pieces were struck in the second half of 1973, though they were dated 1974. At congressional hearings, representatives of the vending machine industry testified that aluminum cents would jam their equipment, and the Mint backed away from its proposal. These 1974 aluminum experimental pieces were almost all melted, but some have found their way to private hands. Samples of the aluminum cents had been distributed to members of Congress, but 14 remained missing, with the recipients claiming to not knowing what had happened to them. One aluminum cent was donated to the Smithsonian Institution for the National Numismatic Collection.

In 1982 the price of copper dictated a change in the composition of the Lincoln penny. Because of rising copper prices, the U.S. Treasury authorized the usage of a copper-plated zinc as the composition for the one-cent coin. The mint struck approximately half the 1982 pennies from the copper alloy. The rest were made with a copper plating over a zinc core with a copper composition of only 2.5%. This resulted in some 1982 pennies being made of copper and others being struck with a zinc core. All U.S. pennies made for circulation since 1983 contain a zinc core covered with a thin plating of copper.

The United States Mint produced Lincoln Memorial cents at three different mints: Philadelphia (no mint mark), Denver (D) and San Francisco (S).

Lincoln Shield Cent (2010 – present)

Lincoln Shield Cent (2010 – Present)

The Lincoln Shield Cent was issued following the four different designs issued for the 2009 Lincoln Bicentennial Cent to celebrate Lincoln’s birth. The same legislation that authorized the four reverse designs, also specified a fifth design to be issued in the following year, 2010, which would be emblematic of Lincoln’s preservation of the United States of America as a single and united country.

Initially, 18 designs were submitted to the Commission of Fine Arts and the Citizens Coinage Advisory Committee. Both organizations submitted their recommended designs to US Treasury Secretary Timothy Geitner, who selected the Union shield design. Lyndall Bass, an associate designer with the US Mint created the design, and Joseph F. Menna was the design sculptor. In 2010, a new permanent reverse design featuring a Union shield was placed on all Lincoln cents was released on February 11, 2010, one day before the 201st anniversary of Lincoln’s birth.

The "Preservation of the Union" reverse design is emblematic of President Abraham Lincoln's preservation of the United States as a single and united country. The design selected features the Union Shield, which dates back to the 1780’s and was used widely during the Civil War. The shield includes thirteen vertical stripes joined by an upper horizontal bar. This represents the thirteen original states joined together in a single compact union in support of the federal government. The design includes the inscriptions “United States of America” around the top of the coin, “E Pluribus Unum” (Out of Many, One) on the header at the top of the shield, and “One Cent” within a scroll draped across the shield. The obverse continues to bear the Lincoln portrait that has appeared on the coin since 1909.

In early January 2017, cents bearing the current date and with the mint mark “P” appeared in circulation. The Mint had made no announcement of such coins, but confirmed their authenticity, stating that the coins had the mint mark to honor the Mint's 225th anniversary. 2017 is the only year that Philadelphia cents have had a mintmark, cents struck in 2018 and after omit the “P” mintmark.

2019-W Lincoln Cents-A U.S Mint First Ever

2019-W Lincoln Cents-A U.S Mint First Ever

2019 was a big year for the Lincoln Cent and series enthusiasts. The U.S. Mint announced plans to include special cents as a premium with three different numismatic product sets.

The fabled West Point U.S. Mint and Bullion Depository struck three “W” mint marked cents, each featuring a different finish. The standard proof finish featuring frosted devices and mirror-like fields came standard in separate packaging with the San Francisco-struck Standard Proof Set. The reverse proof cent featuring brilliantly mirrored devices and frosted fields came standard in separate packaging with the Silver Proof Set, also struck at the San Francisco branch mint. The third West Point-struck cent is the uniform “Uncirculated” finish and came standard in separate packaging on the Uncirculated Mint Set.

These cents are not the first to be struck at the West Point facility, though they are the first to feature the collectible “W” mint mark. In the seventies the West Point Mint struck cents that featured no Mint mark and are not distinguishable from their Philadelphia and similarly anonymous San Francisco-struck counterparts.

These “W” marked premium cents may become some of the most iconic and beloved in the series and represent an excellent beginning for a broader Lincoln cent collection or a small type set.

-

LIVE

LIVE

The HotSeat

57 minutes agoHate Crimes In Cincy + Hiring A White Girl Makes You A NAZI?!?!

648 watching -

25:24

25:24

Stephen Gardner

1 hour ago🔥 RFK Just SHUT DOWN a DISTURBING Problem!

2965 -

LIVE

LIVE

Film Threat

6 hours agoVERSUS: SUPERMAN VS. THE FANTASTIC FOUR | Film Threat Versus

133 watching -

![[Ep 715] The Trump Way: Deals & Peace | Hate Crimes – Brutal Beat Downs | CA Homeless Money Scam](https://1a-1791.com/video/fww1/f5/s8/1/6/3/j/6/63j6y.0kob-small-Ep-715-The-Trump-Way-Deals-.jpg) LIVE

LIVE

The Nunn Report - w/ Dan Nunn

1 hour ago[Ep 715] The Trump Way: Deals & Peace | Hate Crimes – Brutal Beat Downs | CA Homeless Money Scam

238 watching -

2:36:55

2:36:55

Nerdrotic

6 hours ago $2.94 earnedCancel Kurtzman Trek | The Fate of the Superhero Film - Nerdrotic Nooner 502

31.9K2 -

LIVE

LIVE

Viss

4 hours ago🔴LIVE - The Tactics That Lead To Consistent Wins in PUBG!

71 watching -

1:31:50

1:31:50

Russell Brand

3 hours ago“I’ll NEVER Be The Same…This SHOCKED Me” Dan Bongino Breaks Silence & Vows to Reveal “TRUTH” - SF621

149K86 -

1:02:24

1:02:24

Sean Unpaved

4 hours agoGridiron to Diamond: Rookie QBs, Madden 99s, Salary Caps & NIL's Ripple Effect

26.8K -

25:24

25:24

Scary Mysteries

7 hours agoSTRANGE & SCARY Mysteries of The Month - July 2025

25.8K1 -

1:02:02

1:02:02

Timcast

5 hours agoTrump BULLIES Europe Into MONSTER Trade Deal, Europe COPING Over Trump MASTERCLASS

158K100