Premium Only Content

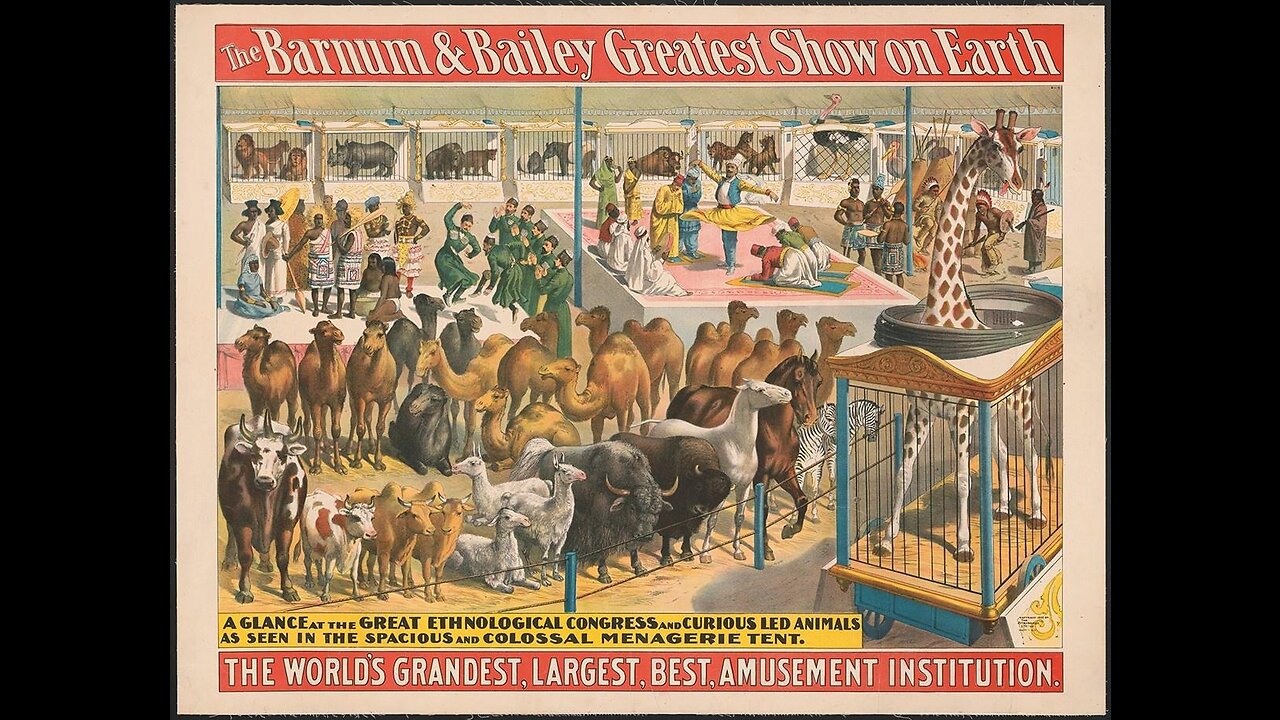

Human Zoos America's Forgotten History of Scientific Racism and The Worlds Fair's

Human Zoos tells the shocking story of how thousands of indigenous peoples were put on public display in America in the early decades of the twentieth century. The harmful exhibition and practices displaying humans that are known today as “Human Zoos” took place for centuries, and their impact can still be seen today. Colonial exhibitions and fairs, circuses, zoos, and museums all took part in exhibiting people from across the world that were deemed other and, thus, curious to observe by white masses that deemed themselves superior and more civilized. In some cases, entertainment was elevated through the incorporation of thrilling performances and the display of exotic animals, further animalizing and dehumanizing exhibited humans. One of the most influential individuals in this exploitation was a man named Carl Hagenbeck. While he is mostly known for his impact on zoo architecture, he was also a prominent wild animal trader and trainer, and an “ethnographic showman.” Along with large names like P.T. Barnum, he further popularized “Human Zoos” at the turn of the twentieth century. One of the most infamous exploitations of an individual involves a young man named Ota Benga. In 1904, an American missionary and explorer was hired by the St. Louis World’s Fair to “acquire” an African pygmy to the fair for exhibition. Benga, from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (then known as the Belgian Congo, a colony of Belgium), was purchased by the missionary from the Baschelel tribe for “several bags of salt and a spool of brass wire,” according to an interview with the missionary’s grandson, likely at a slave market (another product of colonization).

After being exploited at the fair without pay, the missionary returned Benga and other captured African Pygmies to their home. But when he discovered that all members of his tribe had since been killed, Benga did not feel at home and asked to return with the missionary to the U.S. Subsequently, William Temple Hornaday, then Director of what is known today as the Bronx Zoo, inquired with the missionary if he could exploit Benga to maintain the elephant enclosures. Over time, Hornaday discovered that people were coming to see Benga and thought that exhibiting Benga would be a great opportunity. It is reported that up to 40,000 people came to the zoo every day to see Benga in a cage or doing the odd task.

Through the efforts of a group of Black ministers, the Bronx Zoo closed the exhibit and Benga was released. He was moved to Brooklyn and then Lynchburg, Virginia where a number of families housed him, and tried to "educate" him and lead a "normal" life. In March of 1916, Ota Benga ended his own life.

Over 100 years later, the Wildlife Conservation Society, which manages the Bronx Zoo, issued an apology. Often touted as "missing links" between man and apes, these native peoples were harassed and demeaned. Their public display was arranged with the enthusiastic support of the most elite members of the scientific community, and it was promoted uncritically by American's leading newspapers. This award-winning documentary explores the heartbreaking story of what happened, shows how African-American ministers and other people of faith tried to push back, and reveals how some people today are still drawing on Social Darwinism in order to dehumanize others. The film also explores the tragic story of eugenics in America, the effort to breed human beings based on Darwinian principles.

In 1900, the Denver Zoo was four years old. Owned by the City of Denver, it occupied a corner of the newly established City Park and exhibited a small collection of local hoof stock, birds, and other furry mammals—stitched together by delicate fences and simple cage-work.

That year, the city brought members of the Jicarilla Apache Nation, referred to as the “Wild Apaches,” to City Park. The emerging zoo served as a backdrop for their encampment.

According to newspaper articles, a Colonel C. E. Ward was recruited to “obtain permission for a band of the warlike Apaches to visit Denver.” For nine days, the “party of twenty Apaches” gave “exhibitions of village life” at City Park.

Further, one article stated, “weirdness will be added to the latter by having it done on a big float out in the lake.” The perceptions rooted in the concept of the “Human Zoo” survive today. From human safaris to referring to Black, Indigenous, and people of color as “exotic,” whiteness continues to be centered, oppressing anything deemed other. This concept would pave the way for eugenics and pseudoscience racism.

Preconceived ideas about “civilized versus savage” people—the animalization of people—would help shape scientific racism, just one insidious operation of systemic racism that persists today. The name of Carl Hagenbeck is as evocative in Europe as that of P. T. Barnum or Walt Disney in North America. Hagenbeck was the nineteenth century's foremost animal trader and ethnographic showman, known for his enormously popular displays of people, animals, and artifacts gathered from all corners of the globe. The culmination of Hagenbeck's commercial ventures was the opening of his Tierpark near Hamburg in 1907, a dazzling assemblage of constructed exotic environments inhabited by humans and animals.

Eric Ames shows that Hagenbeck's various enterprises illustrate a significant evolution in popular culture. Earlier display forms that relied on the collection and presentation of "authentic" artifacts and living beings - the panorama, the zoological garden, the ethnographic collection - gave rise to the self-consciously synthetic forms of entertainment that we now associate with theme parks and films. This shift took place in the context of Hagenbeck's exhibitions, which were simultaneously the apotheosis of the collecting impulse and the germinating source for the creation of fictional spaces that rely for their effect on the spectator's imaginative engagement and interaction with the spectacle.

Carl Hagenbeck's Empire of Entertainments locates Hagenbeck's myriad enterprises in the context of colonialism and nascent globalization; ethnography and anthropology; zoological gardens and international expositions; museum culture and visual spectacle; and consumerism and immersive entertainments. By tracing out the divergent lineages of themed environments, Ames offers a vivid reconstruction of the impulses and contradictions that lay behind the visual and display culture of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries - a culture that forms the foundation of contemporary themed environments.

Written in an accessible style with many wonderful images, this book draws on meticulous archival research and a wealth of primary sources not available in English. It is an original and entertaining interdisciplinary study that will appeal to readers interested in visual culture, popular culture, nineteenth-century German history, and film studies, as well as anyone intrigued by the history of such popular entertainments as zoos, museums, panoramas, world's fairs, cinema, theme parks, anthropological exhibitions, and Wild West Shows.

For Centuries, Indigenous Peoples Were Displayed as Novelties about the former existence of "Human Zoos" in which Indigenous Peoples were displayed around the globe as novelties and as brutal lessons in imperialism. In 1893 a group of indigenous Aymara Bolivian men traveled to the United States so that they could be put on display at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair Columbian Exposition, which celebrated the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s arrival in the Americas. While researching their story, Nancy Egan, a doctoral student in Latin American history at the University of California, San Diego, delved into the history of indigenous people brought to the United States and Europe and put on display in what she calls “human zoos.”

Indigenous people from all over the world were brought to the United States and Europe and displayed at fairs and circuses during the 1800s and 1900s. Why were these displays so popular?

Egan: Most historians who study these exhibitions agree they were a way of reinforcing or illustrating the racist notions of white supremacy that seemed to be built into the logic of empire and colonialism. Most nations took great care to try and mold the people they put on display into images that justified their own colonial power. In some cases this meant trying to create “savages.” In other cases, they tried to use these displays of human beings to illustrate how the colonial presence was “civilizing” people. These exhibits also played into other forms of popular entertainment. They were a mix of imperial ambition and circus.

You studied a group of indigenous Aymara Bolivians who were brought to New York destined for the Chicago fair, but got stranded in New York. What happened? These men were brought to the U.S. to be displayed at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893, but they never made it to Chicago. They attempted to make a living putting on their own musical shows in New York and Philadelphia, but everywhere they went they were basically told that they weren’t exotic enough. After an unsuccessful tour with a circus through Philadelphia, the group was abandoned by their managers and José Santos Mamani, the member of the group dubbed the “giant” by the press, died shortly after they walked back to New York City. The rest of the group eventually found work in fairs and on Coney Island, but could only find work making feather headdresses and performing supposed North American Native American dances for a New York audience. They struggled to make it back to Bolivia, and I’ve only been able to trace them as far as Panama on their return journey.

How was what Mamani and his companions went through similar to the experience of other “imported” indigenous people who came to the United States? Their story definitely sounds exceptional, but what’s really shocking about the history of these “human zoos” is that it isn’t. One study I read estimated that more than 25,000 indigenous people were brought to fairs around the world between 1880 and 1930. These people struggled under harsh and changing conditions. Many of them had to change their hair, their clothes, their entire appearance to fit the expectations of the organizers and the audiences they were supposed to perform for. Some people were the targets of racist violence while they were on display, while others experienced more subtle forms of violence and were used as subjects of scientific study on racial differences during the exhibition. And, like Mamani, many people died during these exhibitions.

American Indians from the United States were often exhibited alongside indigenous people from other continents. Was the logic behind exhibiting Indigenous Peoples from the United States similar to the logic behind exhibiting Indigenous Peoples from other countries? The U.S. government resisted allowing official exhibits of North American Indigenous Peoples until after Wounded Knee in 1890, and viewed shows like Buffalo Bill’s [Wild West Show] as either a semi-threatening glorification of Native Americans or a crass, unscientific form of entertainment. The U.S. preferred exhibits that showed Native Americans as passive peoples. For example, in Chicago, the organizers worked with the Bureau of Indian Affairs to craft exhibits that would supposedly show how beneficial and “civilizing” reservation life and boarding schools were for Native Americans. After occupying the Philippines in 1898, the U.S. created exhibits of Filipinos that included a “civilizing” school that the people on display had to attend. Shows of people from regions the U.S. had not colonized, such as African peoples at the Chicago fair, played up rumors of cannibalism and their threatening nature. The logic behind these exhibits in different countries was directly tied to their imperial and colonial ambitions, and they tried to craft shows that would show people who had been, or would be able to be, colonized, and sell lots of tickets.

Didn’t some Native American leaders fight against exhibits of indigenous people during the 1800s? One of the most incredible things I found in the archives while researching this work was a series of petitions and letters written from reservations in the U.S. challenging the exhibition of Indigenous Peoples and cultures at the fair. This is a section from a petition from the Creek Territories in 1891 that was signed by more than 100 people expressing the group’s wish to represent themselves through a Native American–directed exhibit at the fair:

“We are almost despairing and it is inevitable that our people trace the cause of that despairing and consequently desperate condition to the very event which with such large expenditures of wealth you are about to celebrate. It is not fitting nor wise that you so celebrate a great event without considering what it meant and still means to a people once great in numbers.… With a Native American or Indian exhibit in the hands of capable men of our own blood, such as are willing and anxious to undertake it, a most interesting and instructive and surely successful feature will be added.”

Another leader, Simon Pokagon, published his Red Man’s Rebuke during the Chicago fair and distributed it to the press and the public-at-large outside of the fairgrounds in Chicago. At every turn, Native American and African American leaders took aim at the racist ideology of the fair, fought these portrayals and argued for the right to self-representation.

Traveling to a different country and sharing time and space with a diverse group of people really changed some of the people who were on exhibit. What did you learn about their experiences?

In the security records of the fair in Chicago I found all these frustrated notes from security guards who were trying to prevent the people from different exhibits from socializing with one another. Apparently people from the different exhibits were hanging out and drinking beer with one another after the fair shut down. In another study, one where historians were actually able to interview indigenous women who had been part of the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904, those women spoke about the relationships they developed with other exhibited women and how they overcame language barriers to share their experiences. I think these stories captivated me because they show the importance of looking at the people who were brought to be exhibited as complete human beings and asking: What did they think about what they saw and experienced? What did they feel about the other people they met? It’s easier to think about these ‘human zoos’ as spaces you look into. Thinking about these men and women socializing and struggling makes me wonder what they thought of these spaces and events as they looked out.

When did “importing” indigenous people to put on display begin to end, and why? Because the rationale behind these exhibits was so closely tied to the logics of empire, or the exhibition of empire, many of these exhibits began to disappear when the European empires began to decline, but they also began to change form before then. In a historical study of these events, titled Human Zoos, several historians propose that these exhibitions began to emphasize showing cultural differences instead of racial ones by the 1920s. However, some forms of these exhibits continued well into the 20th century, and certainly, using the logic of cultural difference to justify political, economic and military domination has not disappeared.

Human zoos: The Western world’s shameful secret, 1900-1958 These shocking rare photographs show how so-called ‘human zoos‘ around the world kept ‘primitive natives’ in enclosures so Westerners could gawp and jeer at them. The horrifying images, some of which were taken as recently as 1958, show how black and Asian people were cruelly treated as exhibits that attracted millions of tourists.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Western world was desperate to see the “savage,” “primitive” people described by explorers and adventurers scouting out new lands for colonial exploitation.

To feed the frenzy, thousands of indigenous individuals from Africa, Asia, and the Americas were brought to the United States and Europe, often under dubious circumstances, to be put on display in a quasi-captive life in “human zoos.”

Human zoos could be found in Paris, Hamburg, Antwerp, Barcelona, London, Milan, and New York City. Carl Hagenbeck, a merchant in wild animals and future entrepreneur of many zoos in Europe, decided in 1874 to exhibit Samoan and Sami people as “purely natural” populations.

In 1876, he sent a collaborator to the Egyptian Sudan to bring back some wild beasts and Nubians. The Nubian exhibit was very successful in Europe and toured Paris, London, and Berlin.

In 1880, Hagenbeck dispatched an agent to Labrador to secure a number of Esquimaux (Eskimo / Inuit) from the Moravian mission of Hebron; these Inuit were exhibited in his Hamburg Tierpark.

Other ethnological expositions included Egyptian and Bedouin mock settlements. Hagenbeck would also employ agents to take part in his ethnological exhibits, with the aim of exposing his audience to various different subsistence modes and lifestyles. Both the 1878 and the 1889 Parisian World’s Fair presented a Black Village (village nègre). Visited by 28 million people, the 1889 World’s Fair displayed 400 indigenous people as the major attraction. The 1900 World’s Fair presented the famous diorama living in Madagascar, while the Colonial Exhibitions in Marseilles (1906 and 1922) and in Paris (1907 and 1931) also displayed humans in cages, often nude or semi-nude.

The 1931 exhibition in Paris was so successful that 34 million people attended it in six months, while a smaller counter-exhibition entitled The Truth on the Colonies, organized by the Communist Party, attracted very few visitors. Nomadic Senegalese Villages were also presented.

In 1904, Apaches and Igorots (from the Philippines) were displayed at the Saint Louis World Fair in association with the 1904 Summer Olympics. The US had just acquired, following the Spanish–American War, new territories such as Guam, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico, allowing them to “display” some of the native inhabitants. In 1906, Madison Grant—socialite, eugenicist, amateur anthropologist, and head of the New York Zoological Society—had Congolese pygmy Ota Benga put on display at the Bronx Zoo in New York City alongside apes and other animals.

At the behest of Grant, the zoo director William Hornaday placed Benga displayed in a cage with the chimpanzees, then with an orangutan named Dohong, and a parrot, and labeled him The Missing Link, suggesting that in evolutionary terms Africans like Benga were closer to apes than were Europeans. It triggered protests from the city’s clergymen, but the public reportedly flocked to see it.

Benga shot targets with a bow and arrow, wove twine, and wrestled with an orangutan. Although, according to The New York Times, “few expressed audible objection to the sight of a human being in a cage with monkeys as companions”, controversy erupted as black clergymen in the city took great offense.

“Our race, we think, is depressed enough, without exhibiting one of us with the apes,” said the Reverend James H. Gordon, superintendent of the Howard Colored Orphan Asylum in Brooklyn. “We think we are worthy of being considered human beings, with souls.”

On Monday, September 8, 1906, after just two days, the directors decided to close the exhibition, and Benga could be found walking the zoo grounds, often followed by a crowd “howling, jeering and yelling.” At the human zoos of the early 20th century, the indigenous people on display faced a number of challenges. African tribal members were required to wear traditional clothing intended for the equatorial heat, even in freezing December temperatures, and Filipino villagers were made to perform a seasonal dog-eating ritual over and over to shock the audience. A lack of drinking water and appalling sanitary conditions led to rampant dysentery and other illnesses.

In most cases, there were no bars to keep those in human zoos from escaping, but the vast majority, especially those brought from foreign continents, had nowhere else to go. Set up in mock “ethnic villages,” indigenous people were asked to perform typical daily tasks, show off “primitive” skills like making stone tools, and pantomime rituals. In some shows, indigenous performers engaged in fake battles or tests of strength.

In the end, there was no outrage over the subjugation of humans that put an end to human zoos. In the years leading up to World War II and beyond, the public’s time and attention was drawn away from frivolity and toward geopolitical conflict and economic collapse.

By the middle of the 20th century, television replaced circuses and traveling “zoos” — human or otherwise — as the preferred mode of entertainment, and the display of indigenous people for entertainment fell out of fashion.

The 1904 World's Fair was St. Louis' first moment in the international spotlight, and the city, the fourth-largest in the nation at the time, wanted to put on its best face for the world. A small city was built in and around Forest Park to house display halls, music halls, restaurants, amusement parlors — just about everything you could imagine.

Including, in a special hollow, a group of pygmies from Africa. They were displayed in all their "savageness," with a walkway over the top so white visitors could literally look down on their fellow human beings and point and laugh.

As historian Angela da Silva explains, this was a far different sort of display than America brought to the 1898 World's Fair in Paris. There was a special exhibit called 'The Progress of the American Negro' at the Paris 1898 World's Fair, curated by W.E.B. Du Bois," da Silva says. "One of the reasons Du Bois did it was to show that there wasn't a monolithic black culture in America. A black man at Smithsonian was charged with finding books by black people for the exhibit. Du Bois was hoping for 200 — he found 3,000. Four years later, black people couldn't get a drink of water on the fairgrounds in St. Louis."

Da Silva's recent research reveals that, while the 1904 World's Fair welcomed the international community to St. Louis, the invitation didn't extend to black St. Louis — unless they wanted to work a menial job behind the scenes or be in one of the anthropological displays designed to "prove" their subhuman nature. It's this research that informs. Some anthropologists believed the pygmies were the missing link between man and monkey," da Silva explains. "I found official portraits that were taken of some of the pygmies, and they're labeled 'Missing Link No. 1, Missing Link No. 2.'" She's had them blown up to life-size so the people can be seen clearly for who they were — human beings. Officially, the fair did not sanction discrimination. But as da Silva found, it didn't need to be sanctioned by organizers; plenty of volunteers and businesses were happy to discriminate on their own recognizance, refusing to serve black patrons food, souvenirs, even water.

"The National Association of Colored Women was holding their conference here July 13," da Silva recalls. "One of the women scouted around on site ahead of the conference and found out she couldn't get served anywhere; 2,000 women said 'hell, no. We won't go,' and they pulled out of St. Louis."

One of the most surprising tidbits da Silva learned in her research was about the Boer War, which was fought between the United Kingdom and descendants of Dutch settlers in South Africa at the end of the eighteenth century — and then was briefly reprised here. "The fair re-fought the Boer War everyday for the crowds," da Silva says through laughter. "The British contingent brought a group of Zulus over from Africa to tend the animals, just like they did during the war. Black St. Louisans would go see them, these tall Zulus. They started talking to each other and the local blacks would tell them, 'You're in America, now. You can leave, you know.' At the end of the Fair, most of the Zulus donned Western clothes and walked out the front gate and blended in."

These are the sorts of forgotten (it's a kinder word than "suppressed") stories that da Silva loves to share. After sixteen years of planning and performing at the Mary Meachum site, she's found that modern St. Louis is eager to learn the truth about its past, warts and all.

"I'm trying to talk about the moments in black history that aren't spoken about," da Silva says of her life's work. "Every year we do this, the crowd is larger. We get a lot of repeat people and there's a lot of kids. Those kids are engrossed. We often wonder if they're taking it all in, how much are they getting? But they keep coming and keep watching."

-

24:03

24:03

What If Everything You Were Taught Was A Lie?

6 days agoThey Lied About Jesus Real Name (Here’s What He Really Taught) A True That You Still Believe It

2.13K5 -

1:06:19

1:06:19

BonginoReport

11 hours agoManhunt Underway for Charlie Kirk’s Assassin - Nightly Scroll w/ Hayley Caronia (Ep.132)

312K244 -

1:11:42

1:11:42

Flyover Conservatives

19 hours agoStructural Architect Destroys 9.11 Narrative... What Really Happened? - Richard Gage AIA | FOC Show

98.6K17 -

1:51:14

1:51:14

Precision Rifle Network

14 hours agoS5E1 Guns & Grub - Charlie Kirk's "sniper"

56.9K17 -

13:09:12

13:09:12

LFA TV

22 hours agoLFA TV ALL DAY STREAM - THURSDAY 9/11/25

416K93 -

1:01:56

1:01:56

The Nick DiPaolo Show Channel

11 hours agoDems + Media Killed Kirk | The Nick Di Paolo Show #1792

131K120 -

1:35:10

1:35:10

LIVE WITH CHRIS'WORLD

13 hours agoLIVE WITH CHRIS’WORLD - WE ARE CHARLIE KIRK! Remembering a Legend

41.4K7 -

50:24

50:24

Donald Trump Jr.

13 hours agoFor Charlie

404K500 -

2:05:22

2:05:22

Quite Frankly

14 hours agoTipping Point USA? & Open Lines | 9/11/25

80.7K8 -

1:04:09

1:04:09

TheCrucible

10 hours agoThe Extravaganza! EP: 35 (9/11/25)

111K36