Premium Only Content

Why The jewISH been Kicked Out So Many Times?

Is It Time for the Jews to Leave Europe?

Usury (charging interest in moneylending, especially at high rates) used to be viewed as a sin by many religions and was banned by many cultures

Although early forms of banking (like depository banking and currency exchange) had been practiced since 5,000 BC if not earlier[3]. Banking was practiced in temples in Ancient Greece, Rome, Egypt, and Babylon.

Sometimes interest rates were set by the state

Although small-time moneylenders might act as loan sharks despite usury bans, usury was outlawed and treated as a sin by most cultures in history.

These included Indian cultures, those that practiced Buddhism, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, and, at points, by the Chinese, Greeks, and Romans.

Early Vedic texts of Ancient India ban usury (2,000-1,400 BC). Plato, Aristotle, the two Catos, Cicero, Seneca, and Plutarch criticize it. Solon removed all debts and credits when Athens had become “enslaved to debt,” and Rome, which had some of the first notable non-Temple banks and early forms of interest, even outlawed it at a point. Not only that, but Islam still essentially outlaws usury today.

History tells us two things. First, that charging interest is as old as minted currency and trade itself. Second, that making money by lending it had long been viewed harshly.

While this may seem good at first, especially when we conjure up images of shifty loan sharks and greedy bankers, there are some serious problems to outlawing all interest charging.

The Implication of Banning Usury

The effect of banning usury and charging interest is that it makes most types of banking (especially commercial banking) impossible. It removes the incentive to lend money.

Charity and other virtues aside, why would a private lender lend money to a grain farmer who needs to the money to grow a crop, but won’t harvest to sell for a season?

Why lend to a grain merchant who buys lots of grain upfront after the harvest for the year or season if not for a cut of the grain, a fee, or some benefit?

Why take a risk for no reward?

Sure, we can, like Dante, who places Blasphemers and those who charge usury in Ring 3 of the Seventh Circle of Hell, John Locke (father of liberalism), or Adam Smith (the father of modern economics) point out that only labor and raw materials can create value.

We can rightly point out that loan shark-like abusive interest rates are unethical and immoral. Those are valid points, and not many would disagree with those basics, but a full ban on charging interest is a harder position to justify.

Reasonable Interest Rates Vs. Usury

Today I would define usury as very high loanshark-like rates designed to extort the borrower like loans that compound at such high rates in short amounts of time as that make paying off the principal nearly impossible.

The ethical difference between charging high interest and any charging interest has not always been made.

Meanwhile, reasonable interest rates are rates designed to incentivize the moneylender and the borrower to take on a relationship of debt and credit that is beneficial to both parties and helps grow the economy (Capitalism).

Reasonable interest rates are an integral part of modern economics and the free-market, and it’s a little prejudice to insinuate that banking isn’t labor or that a loan has no value worth charging a fee over.

Meanwhile, extortion in any area of life is always a bad thing, but banning interest isn’t any more a solution in banking than banning prostitution is a solution for eliminating sexually transmitted disease.

Still, logic aside, in practice in and around the 1,100’s Europeans were dealing with strict anti-usury laws and church doctrine that fully banned interest of all types.

At the time usury was defined strictly as, “anything beyond the principle [the original amount] is usury,” and that wasn’t going to propel trading-Republics into the future.

Quidquid sorti accedit, usura est (“Whatever exceeds the principal is usury”) – God’s word (as interpreted in Europe at the time)

The Problem of the Italian Grain Industry and the Re-Birth of Discounting

The hard-line, but common, stance against usury was hampering the grain and farming business of the Italian merchants and farmers.

Those business, as noted above, benefited greatly from all types of banking including currency exchange, deposit, loans, futures trading, insurance, etc.

The Roman Empire had eventually allowed loans with carefully restricted interest rates, but the Christian church in medieval Europe had since banned the charging of interest at any rate. This left the merchant grain banks with a problem.

The Merchants and Bankers of Venice

Luckily (from a modern perspective at least), although the Jewish faith also treated usury as a sin, a loophole was found that allowed a fee to be charged for interest via a process called “discounting.” Discounting was the process of charging a fee that technically skirts the direct charging of interest, at least compounding interest; Muslims still do this today to allow for banking in their culture despite their current usury ban.

The Jews had been attracted to the trading culture Italian Maritime Republics after having been expelled from Spain and England.

They had found the loophole in their Old Testament

It says, that while a Jew can’t charge another Jew interest, he can charge interest to a foreigner

“Thou shalt not lend upon interest to thy brother: interest of money, interest of victuals, interest of anything that is lent upon interest. Unto a foreigner thou mayest lend upon interest; but unto thy brother thou shalt not lend upon interest; that the Lord thy God may bless thee in all that thou puttest thy hand into, in the land whither thou goest in to possess it” (Deuteronomy 23:20-21).

Jews took the banking practices developed in England, Spain, and the Silk Road and went on to Italy to play the role of bankers for the grain merchants while the Italian Grain merchants themselves became borrowers. This relationship can be seen as the origin of the modern banking system, insurance, stocks, and most other modern financial products.

Learn more about the History of Banking.

Moneylending, Usury, and the West

Although the final notes below deserve their own page, if not their own book or full essay, the takeaway from this should be the following points:

Interest charging allows for banking; liberalism allows for interest charging; the principles that the West were founded on depend on the ability to charge interest. World peace and world war both require a system of debt and credit. This is one of many reasons we can point to banks and bankers as being neutral entities in most cases. They are seldom the cause of war, but they do handle deposits and loans for both sides.

There are two types of interest: 1. reasonable and vital rates like the Federal Reserve uses to ensure the American economy, the type that makes the world go round’. 2. the loanshark kind that we can catch glimmers of in credit card debt charged to our poorest, the housing crisis, student loans, and other more risky gambles. Risky gambles look good on paper, but upsets like hyperinflation in Germany (see Economic effects of the Treaty of Versailles) and inflation in Spain are just the sorts of things that whip people into a panic and lead to persecutions in history. They rarely working out well for any party involved and, ironically, this is often not directly the fault of the banks or those being persecuted.

How societies utilize banking and regulate interest rates will be a big part of whether we sink or swim as a global people. History shows us that we have often over-corrected (banning all interest charging and thus hurting state growth and the free-market), blamed “the Jews,” Capitalists, or Liberals (not just the moneylenders, but an entire race or ideology as a people), and called it a day. But this is a mistake, not just an ethical and moral mistake, but a practical one. Banking is a naturally arising system; it is very short sighted to blame an entire people for remembering how it works when others cast it aside in darker ages (even when not all the fruits it bears are good).

But of course, it is also short-sighted to forget about how those high rates cooked up in the gray areas of the practice have come back to bite everyone in the behind time and time again. The sooner we realize the importance of interest, while respecting the roots of the sin of usury, the better.

“A high interest decays trade. The advantage from interest is greater than the profit from trade, which makes the rich merchants give over, and put out their stock to interest, and the lesser merchants break.” – John Locke, father of liberalism and sometimes economist, presents this quote when arguing that interest is vital, although “high-interest” (usury) is bad.

Not only were Jews the designated moneylenders of medieval Europe, many regions of Europe explicitly banned Jewish land ownership and craftsmanship. Such bans were prominent in Western and Central Europe, particularly from around the end of the First Crusade until the late 18th and early 19th centuries, when Napoleon extended citizenship to Jews in France. In many areas of Europe, including regions of modern-day France, Germany, Italy, and others, the Jewish populations were confined to living in ghettos, segregated Jewish quarters in urban areas, and were barred from living on arable land. While Jews were at times permitted to practice certain crafts, they were largely excluded from the powerful crafts guilds. In many instances, the ban on Jews learning manual skills extended so far that Jews could not even be their own carpenters and architects. For example, the 16th- and 17th-century Jews of the Venice ghetto had to hire Venetian Christian architects to build their synagogues. Thus, Jews were prevented from engaging in what natural law adherents called productive labor and then castigated and penalized for not participating in such fields. Confined only to hated professions, Jews were then hated for practicing those professions.

Confined only to hated professions, Jews were then hated for practicing those professions.

It was only with the Enlightenment and the subsequent period of industrialization that European prejudices began to break as leading philosophers rejected the prohibitions against finance that so thoroughly permeated the medieval world. As Muller notes, Montesquieu wrote in 1748 that, “We owe all the misfortunes that accompanied the destruction of commerce to the speculation of schoolmen.” In other words, Montesquieu argued, summing up a position shared by other Enlightenment philosophers, European economic development had been stunted for centuries due to the philosophizing of theologians. Most famously, Adam Smith in his Wealth of Nations extolled the virtue of accumulating wealth not solely through craft and agriculture, but through fostering economies of scale—a process that requires financial institutions. Smith even supported lending money at capped interest rates to qualified borrowers.

But the pro-finance sentiments of Smith and Montesquieu did not go unchallenged as the large scale economic shifts and rampant inequality of 19th-century industrialization led many philosophers to double down on the medieval contempt for finance—most notably Karl Marx. While the political radicals of the 19th century did not explicitly extol natural law theology, and were often committed atheists, they nevertheless betrayed its influence in their emotionally charged distinction between productive and parasitic labor, and the particular vitriol they showed toward both finance and Jews.

In his infamous essay, “On the Jewish Question,” Marx wrote: “The Jew has emancipated himself in a Jewish manner … because money has become a world power. … The Jews have emancipated themselves insofar as the Christians have become Jews.” That is, in so far as Jewish people had found social or political acceptance, it was only because the world had become more perverse. The world was becoming one in which finance was less and less considered an unmentionable occupation for designated outcasts, than a standard, accepted profession. Finance was still a long way from the prestige that it would gain in the 20th century, but its growing normalization kindled fear and anger, much of which was directed into a growing body of anti-Semitic conspiracies. People whose lives were destabilized and impoverished by unscrupulous labor practices and unregulated technological change could pin their hardships on the twinned evils of finance and the Jews. For anti-Semites of both the left and right—and in the 19th century there were still powerful strains of right-wing anti-capitalism—the political emancipation of Jews was thus the result of turning the world “Jewish”; the Jews freedom purchased through the immiseration of others. The template created by Marx and other 19th-century thinkers who connected their opposition to finance and capitalism with the purported “Jewishness” of those practices would proliferate in subsequent decades, taking root in cultures outside Europe, as financial capitalism also spread across the globe.

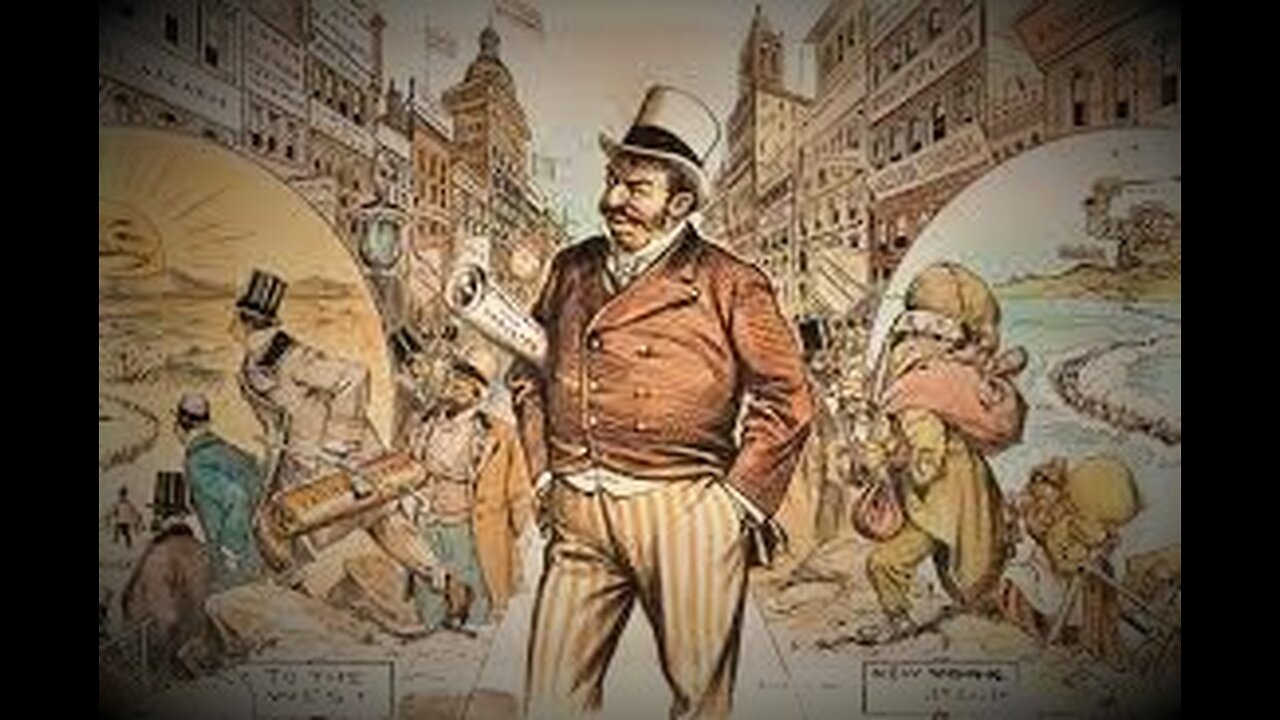

Throughout American history, key figures and political movements have divided the U.S. between two classes of people: rural farmers who support a decentralized government, and urbanites working in commercial and financial professions who favor a stronger national government. The hardworking lone agriculturalist known as the “yeoman farmer” has been an esteemed cultural figure since the days of Thomas Jefferson. Likewise, the Hamiltonian supporters of strong government and administrative professions are often cast as the “evil bankers in New York,” smeared in populist rhetoric as villainous manipulators of land and currency, corrupting a pure way of life and preventing “honest, hardworking” folks from making a living. The trope that there are essentially two forms of professions: honest ones that cause a person to break a sweat, and dishonest ones that exploit true labor, has not only survived since Aristotle, but remains a powerful force in popular culture and political thought, animating deep resentments while obscuring the more complicated, and less starkly moral, nature of work and economic production.

In fact, pitting finance against agriculture and craftsmanship obscures the mutually beneficial potential of the two sectors. Commodities trading, for example had its start in ensuring money to farmers even before knowing their crop yield, encouraging farmers to continue to grow staples and protecting them against going bankrupt due to a bad season. Finance, when subject to smart and good-faith regulation, is ultimately a way to raise funds and spread risk so that people can start or expand businesses, or continue working in a necessary field despite uncertainty. Finance in itself should not be conflated with the particularly American political propensity for dismantling regulatory laws that rose to prominence in the 1980s but has existed in various forms in our nation’s history.

There is a cyclical nature to the political movements emphasizing the division of “productive” from “parasitic” labor. Not surprisingly, they are strongest in periods of economic turmoil. For more than a century during America’s economic downturns, populist political leaders have rallied people by expounding on the Jeffersonian motif of an idealized, self-sustaining pastoral way of life that has been sabotaged by the bankers in New York tinkering with the economy. Certainly, not all populism is bad, and indeed, most populist movements have brought to light the reality of economic insecurity and exploitation. But populist vitriol about finance can walk hand in hand with anti-Semitism. William Jenning Bryan’s 1897 “Cross of Gold” speech is a classic of 19th-century American populism, yet historian Richard Hofstadter notes in his Age of Reform that perhaps nothing did more to reinvigorate American anti-Semitism than the frequent allegations that the “Shylocks” and “Rothschilds” controlled the banks that controlled the farms.

In the 1930s, during the Great Depression, populist challengers to Franklin Delano Roosevelt often fostered anti-Semitism while they campaigned against finance. Huey Long, governor of Louisiana and senator who ran as a third-party populist candidate to the left of FDR, inveighed against the millionaire classes and the bankers. While Long himself did not use overtly anti-Semitic rhetoric, he hired the virulent anti-Semite Gerald L.K. Smith to organize one of his popular campaign programs. Meanwhile, Father Charles Coughlin, a populist radio show host with a large following, routinely lumped Jews in together with communists and bankers as agents responsible for the Depression, reprinting The Protocols of the Elders of Zion in his own periodicals.

It is precisely this history that makes it incumbent on opponents of economic inequality, like myself, to pause and consider our language. Certainly, an economy that has been deregulated to the point that businesses put shareholder profit above raising their employees’ wages, or an economy that does not collect enough revenue to support government services, does not deserve support. The issues to care the most about are our nation’s shortage of stable, well-paying jobs, our difficulty providing basic programs to our citizens, and an underlying national ethos that makes many Americans believe that those suffering “deserve it.” The greater issue facing the U.S. is not anything intrinsic to the nature of finance, but the overfinancialization of our economy—the rampant deregulation of financial products coupled with the primacy our businesses give to shareholders and incentives to do so that Congress has written into our tax code for the past several decades. But as a Jew, I am aware of the dangers in conflating a call for structural reforms of our government and economy with the moral demonization of the financial industry’s intrinsic nature.

Undoubtedly, smart candidates with detailed policy plans like Elizabeth Warren are in a hard place: Their very precision and breadth of knowledge can alienate voters. Politicians who shy away from the politics of outrage can lack the emotional magnetism of a candidate like Bernie Sanders or Donald Trump, whose anger over injustices, real or perceived, is felt by voters as much-needed empathy. But we must be wary of the populist style of paranoid political outrage because too often riling up a hatred of the “elites,” deployed as an emotional charge rather than a specific critique, leads to the demonization of Jews. Elizabeth Warren has long been the candidate of nuance, which is why I admire her; and I hope that she and others will continue to make the legitimate disagreements with economic policy that are not only impassioned but humane, and lead to better outcomes for all Americans instead of offering up scapegoats.

For half a century, memories of the Holocaust limited anti-Semitism on the Continent.

That period has ended—the recent fatal attacks in Paris and Copenhagen are merely the latest examples of rising violence against Jews.

Renewed vitriol among right-wing fascists and new threats from radicalized Islamists have created a crisis, confronting Jews with an agonizing choice.

The French philosopher Alain Finkielkraut, the son of Holocaust survivors, is an accomplished, even gifted, pessimist. To his disciples, he is a Jewish Zola, accusing France’s bien-pensant intellectual class of complicity in its own suicide. To his foes, he is a reactionary whose nostalgia for a fairy-tale French past is induced by an irrational fear of Muslims.

Finkielkraut’s cast of mind is generally dark, but when we met in Paris in early January, two days after the Charlie Hebdo massacre, he was positively grim.

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2015/04/is-it-time-for-the-jews-to-leave-europe/386279/

-

LIVE

LIVE

Benny Johnson

2 hours agoAmerican Martyr: Remembering Charlie Kirk | FBI Reveals New Footage of Assassin, Trump's Eulogy LIVE

8,388 watching -

25:38

25:38

The Rubin Report

2 hours agoRemembering Charlie Kirk & 9/11

44.7K12 -

1:00:32

1:00:32

VINCE

3 hours agoRest In Peace Charlie Kirk | Episode 123 - 09/11/25

249K238 -

LIVE

LIVE

LFA TV

6 hours agoLFA TV ALL DAY STREAM - THURSDAY 9/11/25

5,636 watching -

LIVE

LIVE

Bannons War Room

6 months agoWarRoom Live

10,359 watching -

DVR

DVR

The Shannon Joy Show

1 hour agoA message of encouragement and a call for faith and unity after the tragic killing of Charlie Kirk

8.72K6 -

LIVE

LIVE

The Big Mig™

2 hours agoIn Honor Of Charlie Kirk, Rest In Peace 🙏🏻

3,772 watching -

1:36:35

1:36:35

The White House

4 hours agoPresident Trump and the First Lady Attend a September 11th Observance Event

87.3K34 -

1:38:49

1:38:49

Dear America

3 hours agoWe Are ALL Charlie Now! This Isn’t The End. We Will FIGHT FIGHT FIGHT

170K182 -

2:09:21

2:09:21

Badlands Media

11 hours agoBadlands Daily: September 11, 2025

53.5K12