Premium Only Content

Panic of 1893 Wall Street and Pullman Company Strike in Chicago 1893 World's Fair ?

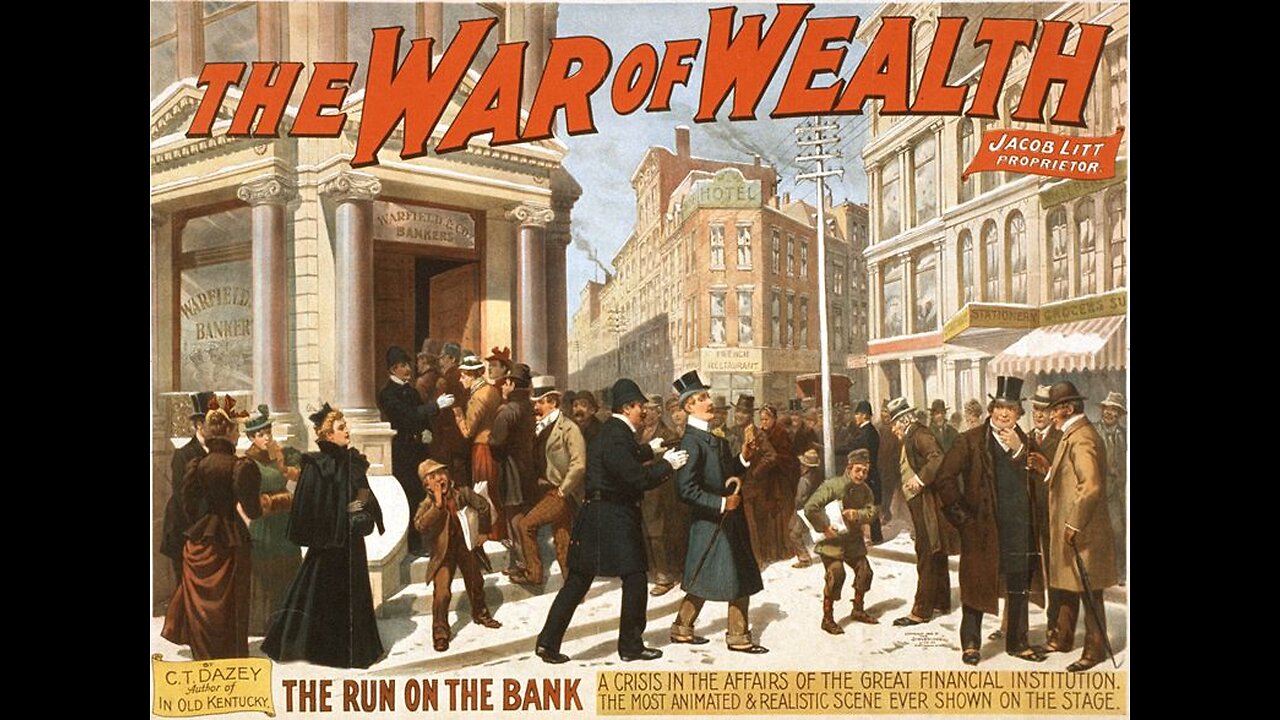

The Panic of 1893 was a national economic crisis set off by the collapse of two of the country's largest employers, the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad and the National Cordage Company. This led to precipitous declines in stock markets, Wall Street brokerage houses, bank failures including 172 state banks, 177 private banks as well as 47 savings banks and 13 loan and trust. Grover Cleveland faced an acute economic depression shortly after being elected to his second non-consecutive term in November 1892 and inaugurated on March 4, 1893. The Panic of 1893 struck the stock market, leading him to borrow $65 million in gold from Wall Street banker J.P. Morgan and the Rothschild banking family of England. A growing credit shortage created panic, resulting in a depression. Over the course of this depression 15,000 businesses, 600 banks, and 74 railroads failed. There was severe unemployment and wide-scale protesting, which in some cases became very violent.

Around 200,000 people crowded into the White City for the opening day festivities on May 1st, but only 10,000 people visited the World’s Fair on May 2nd. This precipitous decline was…less than ideal. Things looked even worse when the Panic of 1893 set off a depression which sent unemployment skyrocketing to over 18% by the end of the year.

While it was later eclipsed by the 1907 financial crisis and the Great Depression, the Panic of 1893 remains one of the most severe financial crises in American history. Its impact on Sierra County, New Mexico was lasting. Silver mining towns, like Kingston, were all but abandoned in short order.

The panic, and the economic depression that followed through the year 1897, had wide-ranging effects on the national economy, including an unemployment rate that remained stubbornly above 10 percent for five consecutive years. Its impact goes beyond just the widespread bank runs and the negative effects of high, persistent unemployment; perhaps more importantly, the crisis brought the decades-long debate over the bimetallic standard to the forefront, culminating most colorfully in William Jennings Bryan’s 1896 presidential campaign. Bryan’s “Cross of Gold” speech ended with a flourish: "Having behind us the producing masses of this nation and the world, supported by the commercial interests, the laboring interests and the toilers everywhere, we will answer their demand for a gold standard by saying to them: You shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns, you shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold."

Since bimetallism was an important factor in 1893, as evident in Bryan’s speech, a quick review should be helpful. Starting with the first Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton, the U.S. economy had been on a bimetallic standard. Under that standard, U.S. currency was equivalent to a certain quantity of gold and a certain quantity of silver; initially, the prices were set such that 15 ounces of silver were equivalent to 1 ounce of gold. Because of deviations between this official price and the world market price, only one of the two metals would circulate in the American economy at any given time. From Hamilton’s 1792 coinage act until 1834, silver was in circulation because gold was undervalued at its official price; therefore, it made economic sense to export gold coins to Europe, exchange them there for silver, then import that silver back into the U.S. This all changed in 1834 when the official ratio was changed to 16 ounces of silver per 1 ounce of gold, which then made gold overvalued so that it slowly began to replace silver, which was either hoarded or exported. Starting in 1834, the U.S. moved to a currency system where gold was the circulating coin. Silver dollars remained largely out of circulation from 1836 until the 1873 coinage act.

At first, the 1873 act seemed only to legally recognize the demonetization of silver dollars; after all, they had not been used since 1834. Even the representatives of the silver interests in Congress did not object to the legislation. But in a curious twist of history, what was thought to be mere legislative housekeeping quickly became a highly politically charged issue. Silver prices had started to fall in 1872, but the decline accelerated shortly after the 1873 legislation mostly because of increased silver supplies from new mines in the American West. Because of the falling silver prices, U.S. silver producers had an incentive to bring silver to the U.S. mint for coinage. They did just that only to discover that they were legally barred from having silver coined by the 1873 legislation, which they quickly dubbed the “crime of ’73.”

By 1878, the silver interests were successful in getting Congress to pass the first of two significant silver purchase laws, the Bland-Allison Act, but the pro-silver interests were not satisfied because that legislation did not provide for unlimited coinage of silver. The second significant Congressional action did not come until the 1890 Sherman Silver Purchase Act. This legislation also failed to provide for unlimited silver coinage but it did increase the amount of silver purchased every month by the U.S. government, and by then, silver mining was in full-swing in Kingston and Lake Valley, New Mexico.

All of this led to considerable uncertainty by the early 1890s as to whether the U.S. economy could remain on the gold standard. Adding to the problems, the Treasury’s gold reserves had fallen to dangerously low levels by 1893; this was exacerbated by news that the Treasury would stop redeeming the notes issued under the 1890 act in gold if the reserves fell below $100 million.

These long-running issues of gold versus silver certainly played a role in the 1893 crisis but there were many other contributing factors. Important among them were significant distress in western agricultural markets caused by declining crop yields and falling agricultural prices. Another factor in the depression was the slowdown in railroad construction that had peaked in the railroad boom of 1880s. Moreover, American exports to Europe had dropped as European economies struggled.

The crisis culminated in the summer of 1893 with widespread bank runs. Of course, this was long before the introduction of federal deposit insurance (that does not arrive until 1933), so any risk that a depositor’s bank would fail tended to immediately lead that depositor to withdraw funds from the bank. Bank runs, wherein large numbers of depositors did just this, spread rapidly and, while they occurred nationwide, they were concentrated in the western states. In total, nearly 500 banks in the U.S. suspended their operations at least for a time to weather the storm. The economy officially went into recession in January 1893, a few months prior to the waves of bank runs that hit that summer. The affect was felt locally -- Kingston being a silver town was abandoned and never rebounded. After a brief economic recovery in late 1894 and into 1895, the economy plunged back into recession by the end of 1895 and would not officially climb out of recession until the summer of 1897.

A legacy of the 1893 crisis remains with us today: the National Monetary Commission, whose work and recommendations led to the formation of the Federal Reserve System in 1914, noted in its report on financial crises that, while the causes of crises were varied, the method of handling them was simple. There should be, the report concluded, a reserve of lending power because the ability to increase loans from a central reserve to meet the demands of depositors “would have allayed every panic since the establishment of the national banking system [in 1864].” Locally, the hillsides around Kingston are pocked with the work of expectant silver prospectors in what they left behind.

The economic collapse of the Philadelphia and Reading Railroads was the first step toward the Panic of 1893. A growing depression in Europe resulted in British investors selling their American investments and redeeming them for gold. This fostered a growing American gold loss, creating a panic. There was a run on the banks and over 500 were forced to close

By May 15, stock prices reached an all-time low. Many major firms; such as the Union-Pacific, Northern-Pacific and Santa Fe railroads; were forced to declare bankruptcy. Unemployment steadily grew, rising from 1 million in August 1893 to 2 million by January 1894 By the middle of the year, the figure had reached 3 million.

The government had no plan to end the economic panic. President Cleveland blamed the Sherman Silver Act and Congress repealed it, but that had little impact. Most relief for those without jobs was provided by local voluntary organizations, who were quite overwhelmed by the need.

The Pullman Strike began at the Pullman Company in Chicago after Pullman refused to either lower rent in the company town or raise wages for its workers due to increased economic pressure from the Panic of 1893. Since the Pullman Company was a railroad car company, this only increased the difficulty of acquiring rolling stock. The maritime industry of the United States did not escape the effects of the Panic of 1893.

The Pullman Strike began in Chicago on May 11, 1893 when nearly 4,000 factory employees of the Pullman Company began a wildcat strike in response to recent reductions in wages. This conflict pitted the American Railway Union (ARU) against the Pullman Company, the main railroads, the main labor unions and President Grover Cleveland of the United States. In May 1894 this strike and boycott shut down much of the nation's freight and passenger traffic west of Detroit.

The Pullman Strike began in Chicago on May 11 when nearly 4,000 factory employees of the Pullman Company began a wildcat strike in response to recent reductions in wages. This conflict pitted the American Railway Union (ARU) against the Pullman Company, the main railroads, the main labor unions and President Grover Cleveland's federal government. It effectively halted rail traffic and commerce in 27 states stretching from Chicago to the West Coast.

What Was the Opening Day of the 1893 World’s Fair Like? The opening day of the 1893 World’s Fair was a big deal! Chicago welcomed visitors from around the world to the opening ceremony of the World’s Columbian Exposition on May 1st. We’re celebrating with a special event, “A Day at the 1893 World’s Fair” virtual tour on April 30 or May 9. In this one-hour virtual event we share what it was like to be among the throngs of people at the Columbian Exposition, seeing jaw-dropping sights and navigating the awe-inspiring exhibits. While researching the event, I wanted to know a bit more about what the opening day of the 1893 World’s Fair was like.

A PRESIDENTIAL INAUGURATION FOR THE OPENING DAY OF THE 1893 WORLD’S FAIR

Chicago has a long, long list of notable presidential visits, but few had as much fanfare as President Grover Cleveland‘s visit on May 1st, 1893. He was one of dozens of civic leaders and dignitaries who paraded down to Jackson Park. The fair’s directors had even invited the Duke of Veragua, a direct descendent of Christopher Columbus. This was, after all, the Columbian Exposition.

The opening day of the 1893 World’s Fair, which garnered breathless press coverage from around the world, centered on President Cleveland’s speech. An estimated 200,000 people crowded into the White City on this opening day. Keep in mind that electronic microphones and amplification were not yet invented. Indeed, the usage of Tesla’s AC electricity to power the fairgrounds was startling and received wide commentary. Still, something tells me that not too many people heard that speech.

Regardless, the key moment needed no words at all. At precisely 12:08pm, on a platform at the head of the White City’s grand Court of Honor, the President pressed a golden telegraph key. According to the Salt Lake Herald…

“The electric age was ushered into being in this last decade of the nineteenth century today when President Cleveland, by pressing a button, started the mighty machinery, rushing waters and revolving wheels in the World’s Columbian [E]xposition.”

It must have been a moment of beauty. I often wonder what event, if any, could similarly excite and unite us now.

AN INCOMPLETE EXPERIENCE

For all that fanfare, the opening day of the 1893 World’s Fair was an incomplete experience. Honestly, it’s sort of miraculous the fairgrounds were ready for visitors at all. Daniel Burnham, the legendary Director of Works, worked mightily to overcome a sea of troubles. The construction schedule was too short. Controversies had arisen over designs. Labor disputes further delayed everything. Thousands of people worked at a fever pitch all through the days leading up to May 1st. A ceaseless run of cold, rainy days (which sounds familiar this year) made laborers miserable. Rainwater swamped Frederick Law Olmstead’s immaculately designed lawns and poured through the roof of expo buildings, according to Erik Larson’s seminal The Devil in the White City.

Perhaps most notably, the star attraction of the Midway was still an unfinished eyesore. The magnificent Ferris Wheel was only a “half-moon of steel encased in a skyscraper of wooden falsework” on opening day. The wheel was Chicago’s attempt to “Out-Eiffel Eiffel” and build a structure as magnificent and romantic as the Eiffel Tower that wowed visitors to the 1889 Paris Exposition. All the same troubles that afflicted the rest of the fair delayed the wheel’s completion until over a month after opening day. Still, everyone marveled when it cranked to life amidst a shower of loose bolts on June 9th.

THE WORLD’S FAIR WAS INITIALLY DISAPPOINTING

It’s easy to forget from our perspective today that the event was initially a flop. Around 200,000 people crowded into the White City for the opening day festivities on May 1st, but only 10,000 people visited the World’s Fair on May 2nd. This precipitous decline was…less than ideal.

Things looked even worse when the Panic of 1893 set off a depression which sent unemployment skyrocketing to over 18% by the end of the year. Civic leaders expected that high attendance would wash away the stains of the clunky opening, but if no one was showing up…

Salvation eventually came in the form of the Ferris Wheel. The fair’s attendance took off when that crazy contraption finally got into motion in mid-summer. Some of that may simply correlate to the generally nicer weather in mid-summer. Still, it’s hard to understate the incredible draw of the Ferris Wheel. The White City might have been a fiasco if not for a ride that wasn’t even on the formal fairgrounds.

REFLECTIONS ON THE OPENING DAY OF THE 1893 WORLD’S FAIR

This gives you a hint to the bigger ideas that pervade our Day at the 1893 World’s Fair virtual event. This new experience puts you in the shoes of a visitor to the brief Columbian Exposition. Opening Day was on May 1st, 1893, and the somber closing day was on October 31st, 1893. This legendary event ran for all of 183 days. By contrast, it’s been 45,472 days since the fair ended. The fair is ancient history by Chicago’s standards; far beyond living memory. Yet it still captures our attention. We still look back to that one summer. Do we see glamour there? Hope? Pride? Wonder? Waste? Triumph? Tragedy? All were present, of course, even as our sense of what a visitor saw, heard, and did has shifted.

More than any single thing, thinking back to the opening day of the 1893 World’s Fair, we’re looking back to see if we can catch a glimpse of ourselves there. By looking back and seeing ourselves we confirm that our own glamour, hope, pride, waste, triumph, and tragedy has a precedent. Such confirmation lets us know that our own great-great-grandchildren might look back at us and our times in the same way someday.

-

10:18:30

10:18:30

What If Everything You Were Taught Was A Lie?

6 days agoOur 1000th Video A True History 70 Unsolved Mysteries That Science Can’t Explain Documentaries

1.56K -

25:57

25:57

DeVory Darkins

1 day ago $10.87 earnedNewsom suffers HUMILIATING SETBACK after FATAL Accident as Trump leads HISTORIC meeting

25K105 -

LIVE

LIVE

FyrBorne

9 hours ago🔴Warzone M&K Sniping: First Impressions of Black Ops 7 Reveal

359 watching -

8:16

8:16

MattMorseTV

15 hours ago $7.76 earnedTrump’s name just got CLEARED.

63.4K59 -

2:01:55

2:01:55

MG Show

19 hours agoPresident Trump Multilateral Meeting with European Leaders; Trump Outlines Putin Zelenskyy Meeting

17K19 -

LIVE

LIVE

DoldrumDan

1 hour agoCHALLENGE RUNNER BOUT DONE WITH ELDEN RING NIGHTREIGN STORY MODE HUGE GAMING

32 watching -

10:59

10:59

itsSeanDaniel

1 day agoEuropean Leaders INSTANTLY REGRET Disrespecting Trump

12.1K14 -

16:43

16:43

GritsGG

15 hours agoThey Buffed This AR & It Slaps! Warzone Loadout!

12.3K1 -

2:05:30

2:05:30

Side Scrollers Podcast

19 hours agoEveryone Hates MrBeast + FBI Spends $140k on Pokemon + All Todays News | Side Scrollers Live

106K11 -

11:06

11:06

The Pascal Show

13 hours ago $1.32 earned'THEY'RE GETTING DEATH THREATS!' Jake Haro's Lawyer Breaks Silence On Emmanuel Haro's Disappearance!

14K