Premium Only Content

Norma McCorvey “AKA Jane Roe” LIED, never had an abortion. “This is my deathbed confession.”

‘Jane Roe,’ from Roe v. Wade, made a stunning deathbed confession. Now what?

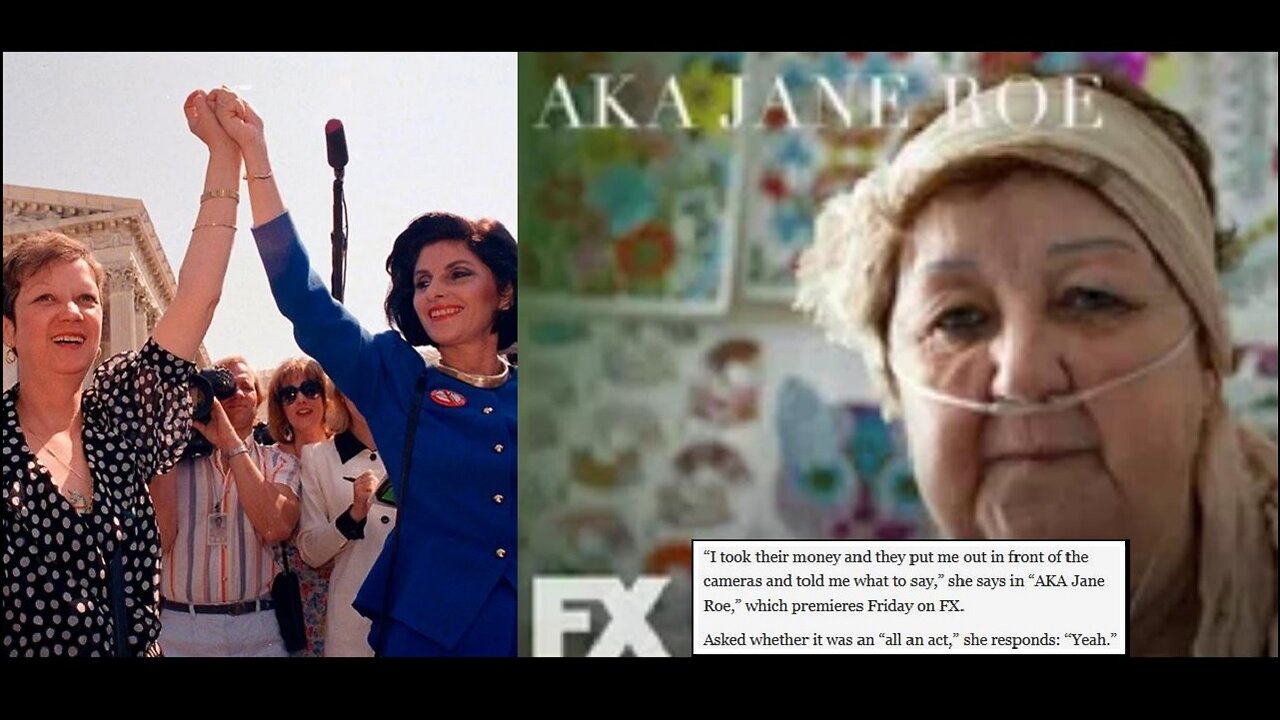

This week [May 2020], a new documentary drops a boulder into the already complicated legacy of the woman better known as “Jane Roe” — the plaintiff in the landmark 1973 case that legalized abortion in America. In the mid-1990s, McCorvey had made a public religious and political conversion. She was baptized on television in a backyard swimming pool; she wore overalls and came out beaming. She declared herself newly pro-life and spent the last two decades of her life crusading against the ruling her own case had made possible.

But in “AKA Jane Roe,” premiering Friday on FX, McCorvey turns to the camera with an oxygen tube dangling from her nose and tells director Nick Sweeney, “This is my deathbed confession.”

She never really supported the antiabortion movement, she tells Sweeney, in a scene filmed in 2017. “I took their money and they put me out in front of the camera and told me what to say, and that’s what I’d say.”

“It was all an act?” the director asks.

“Yeah,” she says. “I was good at it, too.”

The revelation comes 60 minutes into the 80-minute documentary. By minute 70, McCorvey has died, succumbing to illness, leaving the people she knew on both sides of the most polarizing cultural debate in America slack-jawed and stunned.

McCorvey never had an abortion. A lot of people don’t realize that. By the time the Supreme Court handed down its decision, she’d been forced to carry out her pregnancy; the child had already been adopted.

It was her third time giving birth. One daughter had been primarily raised by McCorvey’s mother; McCorvey placed a second child for adoption. McCorvey strung together low-paying jobs in Texas and at various points struggled with substance abuse; she wasn’t prepared to become a parent. Her desperate circumstances were what made her a suitable plaintiff. If she’d had money to travel to a locale where abortion was already legal, her attorneys wouldn’t have been able to argue that the current state-by-state solution placed an impossible burden on their client.

So “Roe” didn’t help McCorvey, but it helped other women like her, and one evening, a Dallas abortion provider named Charlotte Taft was holding a public event at her clinic when a petite, curly-haired woman approached her and said, “I’m Jane Roe.”

The abortion rights movement had the law on its side now. Its supporters didn’t need a public face. “But she put herself out here to say, here I am,” Taft says in an interview.

McCorvey’s life had been hard. Her mother hit her. As a girl, she ran away with a female friend, and when they were caught kissing, she was sent to reform school for punishment. She escaped a marriage to a man who she said abused her and found a long-term partner in Connie Gonzales, but the 1970s and ’80s weren’t always welcoming times for lesbians. Now, though, there was a movement that saw her as a hero. She was offered speaking engagements — local ones at first, and then she met famed feminist attorney Gloria Allred, and the engagements became national. She was funny and vulgar and had the wry, weary wit of an early Roseanne Barr. When a reporter at a news conference asked how much money she made as a maid, she shot back: “Why? Anybody here need a good housecleaning?”

In the early 1990s, a new tenant moved in next to the abortion-related nonprofit where McCorvey volunteered. It was a branch of Operation Rescue, the prominent antiabortion group helmed by a minister who took a special interest in McCorvey.

“When I think about Norma, one of her yearnings in life was to be good,” says Taft. “Being the poster child of the pro-choice movement — she got to be a hero, she got to meet celebrities, she got to have applause and give speeches. But with them, they told her she was finally good.”

Rob Schenck, then a leader in the antiabortion movement in Washington, D.C., remembered opening an email in 1995 from a professional acquaintance in Texas. Norma McCorvey had been saved, the email said. She would be on their side, now.

“I regret now that I thought this,” Schenck says in an interview. “But Norma was the equivalent of a world-class trophy.”

McCorvey’s conversion was a cinematic story, a morality play, and who you thought was good or bad depended entirely on what you thought of abortion. McCorvey was either bad then became good, or she was good and then became bad.

“The thing is, we want our stories to be tidy,” Taft says. “And humans aren’t tidy.”

McCorvey certainly wasn’t.

Something that abortion rights activists might not realize: In the 1980s when McCorvey was on their team, she would sometimes call Taft late at night. Usually she’d been drinking, sometimes she was introspective, occasionally she seemed to regret the starring role she’d played in America’s morality play. “The playgrounds are all empty, and it’s because of me,” Taft says McCorvey said one night.

Something that antiabortion activists didn’t realize: In the 1990s, when McCorvey was on their team, she would still tell evangelical leaders that she supported a woman’s right to terminate her pregnancy in the first trimester — the procedure that accounts for the majority of all abortions. “We managed that by saying she’s a brand-new convert; she needs time to mature in her faith and in her understanding of the pro-life ethic,” Schenck says. “We thought, just give her a little time and she’ll mature.” Eventually, they got her to stop saying it publicly, but they didn’t know whether she’d actually changed her mind.

The activists on both sides who knew her found her charming — and found her maddening. She rewrote stories into fantasies. She could be mercenary, and always needed money. Maybe the best word for her was “survivor,” multiple people decided independently. After a rough life, she’d now do whatever it took to survive. At one point in the FX documentary, she chuckles that she’s always “looking out for Norma’s salvation and Norma’s [butt].” At times, she seemed to be exactly what their movements needed. At times, she seemed hellbent on complicating an issue that they found to be absolutely simple and clear.

This made her the perfect Jane Roe, the perfect figurehead of the abortion issue, because it wasn’t simple for a lot of people. Antiabortion activists with accidental pregnancies suddenly find themselves calling Planned Parenthood, convinced that their situations are exceptional. Pro-choice women who terminate pregnancies can move through unexpected grief. At various points in her life, Norma McCorvey represented the issue in all of its complexities and untidiness.

This also made McCorvey a difficult Jane Roe, because movements want their heroes to be pure.

Nick Sweeney wasn’t sure that McCorvey would agree to his documentary. She’d been turning down interview requests for years or demanding payment, which is journalistically unethical (Sweeney says he gave her a “modest licensing fee” to use her family photos and personal video footage in the documentary).

He thinks she agreed to participate because she knew she was nearing the end of her life and because Sweeney hadn’t approached her with an agenda. He didn’t want to make an abortion rights or antiabortion film; he simply wanted to know about her as a person. “There’s a temptation to reduce her to something like a trophy or an emblem, but it’s important to know there was someone who was a real person,” Sweeney says. “People on all sides wanted her to be the person that suited their aims, and in a lot of ways, she just wanted to be herself.”

Does Sweeney believe that McCorvey was telling the truth in her bombshell revelation that she was just faking it for the antiabortion movement? Yes. But does he also believe that she had experienced a sincere religious conversion? Yes.

Did he ask her whether she regretted anything about her choices over the past 20 years? Yes.

And what did she say?

“She said no.”

There’s a scene in the documentary when the clip of McCorvey’s revelation is played back for all of the other participants, one by one. Robert Schenck, Charlotte Taft, Gloria Allred — they all hear McCorvey say, “I took their money and they put me out in front of the camera and told me what to say.”

One by one, they all gasp.

“It felt like such a betrayal,” Taft says in an interview. “The stakes were so high.”

“Seeing it was shocking to me,” Schenck says in an interview. “Not because of what it revealed about her, but what it revealed about me and the movement. She forced me to be honest with myself.”

The antiabortion movement had used her, he thinks now. They’d used her image, and her story, and her regret, and they’d shaved off all the rough edges, turning her into a perfect poster girl instead of a person.

Which is so easy for people to do with abortion. Get so caught up in scrambling for the moral high ground, you forget about the women underfoot.

In recent years, Schenck has had his own reckoning with abortion. He used to be an absolutist: no exceptions, no excuses, no justifications. In recent years, his position has softened; he understands why some people’s life circumstances might make abortion the best option for them. And he’s grown disillusioned about the public debate around abortion.

“Realizing how much the political leaders on both sides had exploited the issue — that seemed to be very problematic, morally and ethically,” Schenck says. “I’m not ready to celebrate abortion; I still think it represents a tragedy and a failure. But I think the human realities around it make it understandable.”

So, what to make of Norma McCorvey? Maybe she works best as a symbol of a different kind of struggle — personal, not political. It’s the struggle that comes with trying to reconcile our untidy, doubt-ridden, trophy-seeking inner monologues with the roles we inhabit in America’s morality play.

In the end, McCorvey seemed to make a sort of peace with the legacy of Jane Roe. “Women have been having abortions for thousands of years,” she says near the end of the documentary.

“If it’s just the woman’s choice, and she chooses to have an abortion, then it should be safe. Roe v. Wade helped save people’s lives.”

To be continued?

Our work and existence, as media and people, is funded solely by our most generous supporters. But we’re not really covering our costs so far, and we’re in dire needs to upgrade our equipment, especially for video production.

Help SILVIEW.media survive and grow, please donate here, anything helps. Thank you!

https://silview.media/2022/05/06/jane-roe-from-roe-vs-wade-made-a-stunning-deathbed-confession/

Learn more: https://silview.media/2022/05/06/jane-roe-from-roe-vs-wade-made-a-stunning-deathbed-confession/

Check out our original memes site: https://truth-memes.com

Buy me a coffee: https://ko-fi.com/silview

-

1:11

1:11

Truths Unlimited

11 hours agoIodine...

862 -

28:31

28:31

Anthony Rogers

13 hours agoBOWLING FOR SOUP interview

871 -

17:12

17:12

Nate The Lawyer

2 days ago $0.11 earnedTrans Swimmer Lia Thomas Stripped of Titles for Being a Man in Women’s Sports

22.4K18 -

12:17

12:17

Zoufry

18 hours agoThe Hunt For The Real Life James Bond

23.4K6 -

24:05

24:05

DeVory Darkins

8 hours ago $7.78 earnedTrump HUMILIATES Jerome Powell in TENSE moment... Columbia University surrenders

98.6K66 -

14:17

14:17

Doc Rich

5 days agoLefties Losing It Once Again

26.3K34 -

25:31

25:31

Liberty Hangout

1 day agoMAGA Crashes Pathetic Anti-ICE Rally

97.3K55 -

2:02:26

2:02:26

Inverted World Live

10 hours agoUS Soldiers Saw Non-Humans in Suffolk, The Rendlesham Forest Incident | Ep. 80

148K24 -

6:42:47

6:42:47

Akademiks

11 hours agoICE MAN EPISODE 2 tonight. NEW NBA YOUNGBOY 'MASA' TONIGHT. BIG AKADEMIKS #2 MEDIA PERSONALITY 2025.

92.9K5 -

2:59:28

2:59:28

TimcastIRL

10 hours agoSouth Park Runs FULL FRONTAL Of Trump In Gross Parody After $1.5B Paramount Deal | Timcast IRL

279K211