Premium Only Content

7 Receptor Selectivity

Receptors are named on the basis of their major endogenous agonist (e.g. adrenergic, serotoninergic, opioid). They are then usually ‘sub-‐typed’ on the basis of their selectivity for agonists or antagonists.

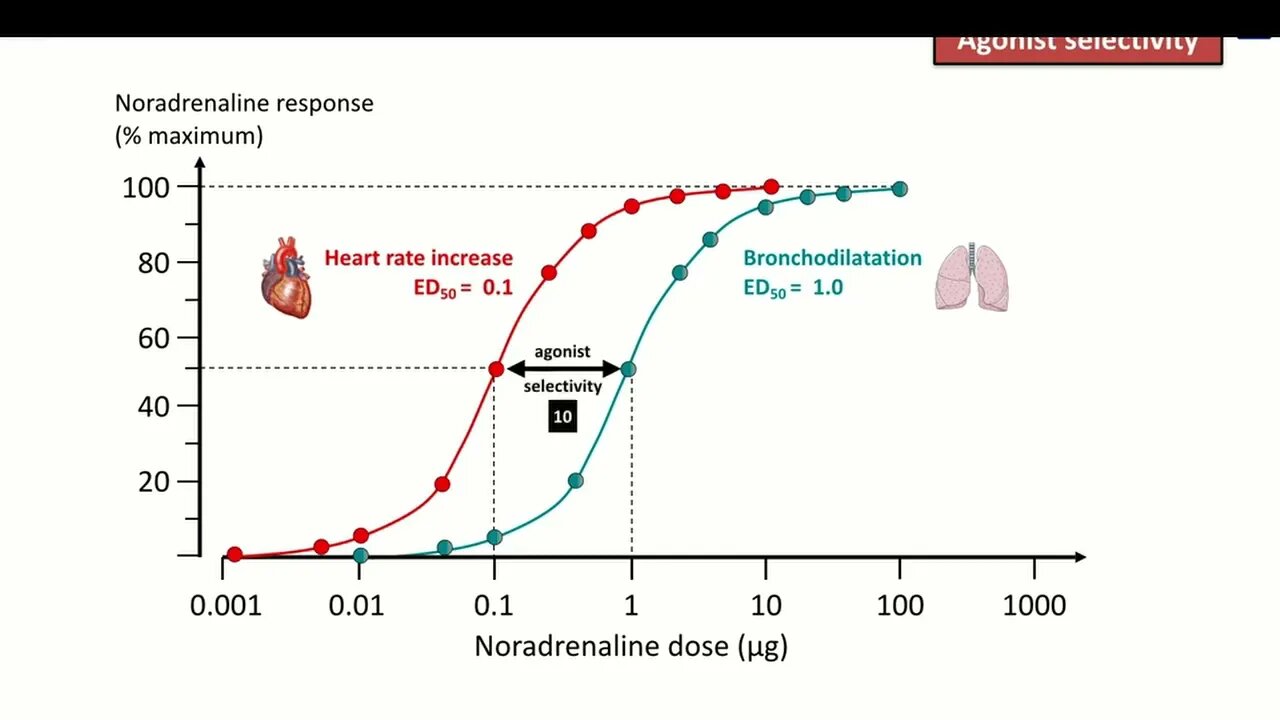

Agonist selectivity is determined by the ratio of EC50 of the dose– response curve at the two different receptor subtypes. For example, β-‐adrenoceptors can be sub-‐typed into β1 and β2, on the basis of their responsiveness to the endogenous agonist, noradrenaline. The concentration required to cause bronchodilatation (via β2 adrenoceptors) is ten times higher than that required to cause tachycardia (via β1 adrenoceptors).

Receptor sub-‐ types can also be distinguished by the relative effectiveness of drugs that antagonize the effects of their full agonist, measured as the relative shift of the agonist dose–response curves achieved by a single dose of antagonist affecting responses mediated through the two receptors. It is important for prescribers to remember that selectivity for a receptor subtype is only a relative concept (i.e. selectivity does not equate with specificity).

Agonist or antagonist drugs that are considered to be ‘selective’ for one receptor subtype can still produce significant effects at other subtypes if a high enough dose is given. This is particularly important if one receptor subtype activates the beneficial effects while another activates the adverse effects. For instance, ‘cardioselective’ β-‐adrenoceptor blocking drugs have anti-‐anginal effects on the heart (β1) but may cause bronchospasm in the lung (β2) and are absolutely contraindicated for asthmatic patients. Selectivity is useful in clinical practice only when the ratio of the impact of the drug at the two receptor sites is 100 or more. When selectivity is lower, it is difficult to predict drug doses that will exploit the difference in subtype activity.

-

1:41

1:41

KimKarcrashian

2 years agoBBC selectivity

173 -

7:50

7:50

Medic Fuel

2 years ago4 Pharmacodynamics Receptor Agonists and Antagonists

69 -

11:50

11:50

Medic Fuel

2 years ago3 Pharmacodynamics Non Receptor Drug Targets

3 -

20:02

20:02

AllHackingCons

2 years agoPyramid Enhancing Selectivity in Big Data Protection with Count Featurization

-

0:54

0:54

onlinedoc007

2 years agoANGIOTENSIN II RECEPTOR BLOCKERS MEDICATION For Your BLOOD PRESSURE. #shorts

1 -

22:53

22:53

Rogerio Gama Arquitetura Fotografia Entretenimento

2 years agoTransmissor e Receptor Sem Fio! Guitarra e Violão! #Review #Unboxing

9 -

![[Review] 2º Receptor/Emissor de Infravermelho, alimentação USB, Extensor de Controle Remoto](https://1a-1791.com/video/s8/1/P/4/6/L/P46Lg.0kob-small-Review-2-ReceptorEmissor-de.jpg) 3:13

3:13

Skooter Unboxings e Reviews

2 years ago[Review] 2º Receptor/Emissor de Infravermelho, alimentação USB, Extensor de Controle Remoto

-

3:49

3:49

Tony Huge UNCENSORED

2 years agoAldactone for accelerated PCT Androgen Receptor Sensitization and steroid side effects

32 -

LIVE

LIVE

The Quartering

2 hours agoDaily Wire CIVIL WAR Over Karmelo Anthony, GTA 6 Trailer Drops, Lady Gaga TERROR Attack & More

13,445 watching -

30:00

30:00

Clownfish TV

9 hours agoDisney Adults: Don't Call Disney Woke!

1.04K10