Premium Only Content

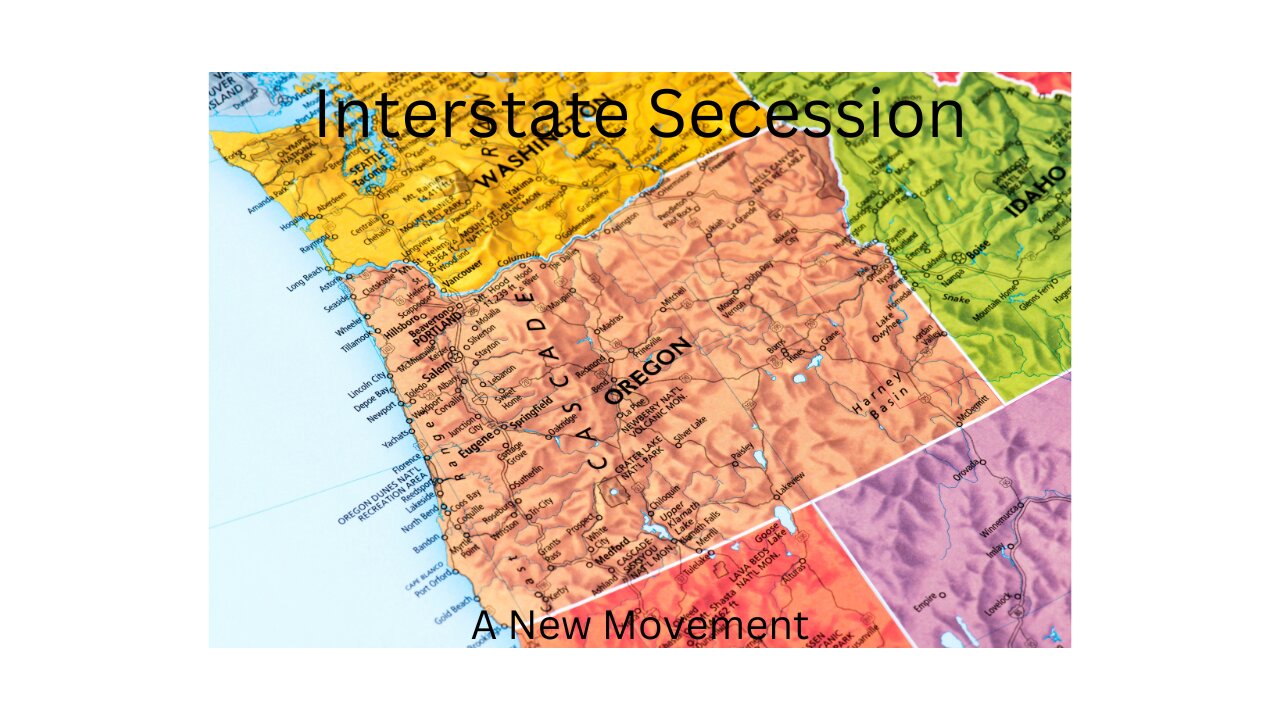

Interstate secession – a new movement

Interstate secession – a new movement

By Terry A. Hurlbut

Interstate secession – when one or more counties want to change State allegiance – is getting more attention lately. Already nine rural counties in eastern Oregon have voted to leave Oregon and join the neighboring State of Idaho. Now the county commissions of Morrow and Wheeler Counties have put the interstate secession question on the ballot for Midterms. (Source: The Washington Times.) This movement relates somewhat to the Great Sortation, with this difference: it involves parts of States seeking different State governments. Herewith a discussion of what interstate secession means, how to bring it about, what stands in the way, and what people in affected territories might do instead.

Interstate secession – what is it?

CNAV has already discussed the secession of a State or States from the Union. We conclude that, contrary to popular belief, the Constitution does not strictly forbid this. The real reason for the War Between the States, if it wasn’t to please some international financiers and arms dealers, was to abolish slavery. Given the cognitive dissonance of Christians trying to defend slavery from the Bible, war became inevitable. No such excuse exists today for the federal government to go to war to stop “red States” from seceding. (The alternative is, of course, for conservative values to win in the next several federal election cycles. That looks far more likely today than a year ago.)

Interstate secession is actually easier than a State breaking away from the Union. The Constitution explicitly provides a mechanism for interstate secession by a county or other local governing unit. The only problem is that it requires the consent of the legislature of the State one wishes to leave. It also requires the consent of the legislature of the State one wishes to join, and of the Congress.

Particulars from the Constitution

The Constitution says:

New States may be admitted by the Congress into this Union; but no new State shall be formed or erected within the Jurisdiction of any other State; nor any State be formed by the Junction of two or more States, or Parts of States, without the Consent of the Legislatures of the States concerned as well as of the Congress.

Article IV Section 3

One or more counties from one State only, seeking to become a State in their own right, would be forming a State within the jurisdiction of another. That concerns the State to which they currently belong, and its legislature must consent. Two or more counties from different States would be forming a State by the junction of parts of those States. Counties joining another State would be forming a State from the junction of the State they wish to join, and their part of the State that now includes them. Either way, that requires the consent of two State legislatures, as well as of Congress.

Never mind the semicolon. What lies beyond the semicolon is not a complete sentence nor even a complete clause. The omission of the word shall from the “junction formation clause” is an elliptical construct. Grammatically, such an ellipsis must never span two sentences. So we read that Article as letting one or more counties form their own State. But to do that, they still need the consent of the legislature of the State they wish to leave.

Current interstate secession movements

The Greater Idaho movement gets by far the most attention among interstate secession movements. The leaders of that movement have drawn a map showing what parts of Oregon they want to include.

Nine counties have already voted Yes on a proposition to secede from Oregon and join Idaho. They are Klamath, Lake, Harney, Malheur, Grant, Baker, Union, Jefferson, and Sherman. Wallowa, Morrow, and Wheeler Counties will vote on interstate secession next. Gilliam, Umatilla, Crook, Deschutes, and Wasco Counties would have to agree before the Greater Idaho movement took its next step. Greater Idaho wants all of Gilliam, Umatilla, and Crook Counties, plus portions of Deschutes and Wasco Counties east of the boundary line (in yellow on the map) they have drawn.

CNAV knows of at least four other interstate secession movements:

• State of Jefferson, that would include parts of northern California and southern Oregon.

• “New California” to split California down the middle, north-to-south. San Bernardino County’s Supervisors voted to consider this, among other options.

• Western Maryland proposing to join West Virginia.

• Several Virginia counties that themselves wanted to join West Virginia to protect their Second Amendment rights. West Virginia’s legislature at least considered extending them an invitation.

The Virginia Pre-Midterm of 2021, that saw the election of Republican Glenn Youngkin as Governor and also “flipped” the House of Delegates, likely acted like a steam pressure relief valve. Virginia interstate secession sentiment has given way to determination to flip the State Senate next year.

Oregon conservatives still outvoted

The prospects of similar “steam pressure relief” in Oregon remain bleak. Greater Idaho movement leaders lament that the urban west of Oregon, especially the cities of Portland and Salem, routinely outvotes the rural and conservative east. So residents of eastern Oregon have been talking interstate secession for more than a year, as NPR reported last year.

The Greater Idaho site lists the advantages of interstate secession to eastern Oregon residents. They point out that 79 percent of the State’s voters live in northwestern Oregon. From that region come the liberal voters that control the Governor’s mansion, the two Senate seats, and the legislature. From that control, Greater Idaho sees:

• Crippling crime,

• Non-punishment of criminal offenders (including “wildfire arsonists,”),

• Infringement of their right to keep and bear arms,

• High taxes,

• Poor forest management that creates a fire hazard,

• Economic stagnation due to taxes and regulation, and

• Lack of effective representation, due to the incessant outvotes.

No wonder they want to leave. But so far, Idaho’s legislature has not yet passed a resolution inviting them to join. (But one Idaho State Representative did ask her colleagues to consider one, according to The Independent.)

Interstate secession does have ample precedent, and not merely the “secession” of West Virginia during the War Between the States. As the Independent reminds us, Kentucky seceded from Virginia in 1792, and Maine from Massachusetts in 1820. Technically, Alabama and Mississippi are both breakaway States from Georgia.

Obstacles to interstate secession, and how to overcome them

Again, a breakaway movement like Greater Idaho needs the consent of three bodies to make their dream real. They are the legislatures of the States they wish to leave and join, and the Congress.

Until this Midterms, Greater Idaho had no prospect of winning the consent of Congress. With Midterms, that will change. Representation in both chambers of Congress would effectively stay the same. Idaho and Oregon would continue to send two Senators from their current Parties. But instead of Oregon sending certain (Republican) Representatives to the House, Idaho would. The one salient practical difference Greater Idaho would make to the Democrats, is in the Electoral College. Oregon’s Second District sprawls across Eastern and Central Oregon – and the Greater Idaho proposed Yellow Line would split it. So Idaho would gain a House seat, and Oregon would likely lose one. Moreover, Pete DeFazio’s seat might flip Republican permanently. That change might, or might not, stop the deal, if Senate rules allow a filibuster on a consent resolution.

Why might Idaho’s legislature invite the Oregon counties to join? Greater Idaho offers these inducements:

• Solidifies the conservative voting majority in Idaho (besides giving Idaho one more Presidential electoral vote),

• Enhances tax revenues, even above what revenues those counties produce today, by reason of Idaho’s low tax and regulation burdens,

• Transfers control of a hydroelectric dam and the rest of a key watershed from Oregon to Idaho,

• Gives Idaho room to grow, and

• Moves Oregon permissiveness farther away.

The big obstacle: consent of the Oregon legislature

That leaves Oregon’s legislature. In order to gain their consent, those who want interstate secession must make either:

• Release of those counties worth the legislature’s while, or

• Retention of those counties not worth the trouble.

Greater Idaho has already suggested what trouble eastern Oregon’s Republican contingent in the legislature could make. They can walk out to deny a quorum, or stall proceedings by moving to have all bills read in full. Greater Idaho offers a simple solution: let us go, and we’ll be out of your hair.

Greater Idaho also points out that highway maintenance in these sparsely settled counties requires a State subsidy. Interstate secession would transfer those highways to Idaho to maintain. Highways aside, Oregon owns very little land in the counties involved.

Finally, State-wide Oregon officeholders could be more confidence of re-election. Not only would conservative eastern Oregon residents become Idaho residents, but current conservative residents of western Oregon would move out. They could then live in Idaho while working in Portland, Eugene, or Salem.

The major disadvantage to Oregon, other than losing an electoral vote, is losing two thirds of its land area. But Oregon would not lose any comparable proportion of its population.

What other trouble could Greater Idaho make?

To make any more trouble than quorum denial or legislative floor stalling, would require far greater cooperation from others. The movement would need the full support of the:

• Sheriff, County Commission (or Board of Supervisors), and Executive or Administrator of each county,

• Legislature and Governor of Idaho, and:

• The Congress, and more particularly the Clerk of the House of Representatives.

The kind of trouble some influencers (like Tim Pool) envision, involves:

• Sending tax revenues, fees, etc. to Boise, not Salem,

• Applying to the Idaho Division of Motor Vehicles, not the Oregon Division, for driver’s licenses and vehicle registration,

• Expanding Idaho’s judiciary and highway patrols into the Oregon counties,

• Making the county boards of elections answerable to Idaho’s Secretary of State, and

• Sending a Representative to Congress nominally from Idaho instead of Oregon.

That kind of trouble, especially the last part, Idaho would never care to make. To be clear, Greater Idaho does not propose making any such trouble. Quorum denial and floor stalling are the limit of the trouble Greater Idaho suggests making.

Alternatives to interstate secession

The obvious alternatives to interstate secession, for any individual resident, are:

• Sell your home and land, if you own any, and move out, or else:

• Campaign – hard – to start winning State-wide elections.

The second alternative is now available to Virginians as it has not been since the days of Governor George Allen. Governor Youngkin won because even traditionally liberal voters saw what was happening in Virginia schools. “We didn’t sign on for this!” they cried. Candidate and former Governor Terence McAuliffe seemed to say, “Oh, yes, you did; now get with The Program.” To which they replied, “Oh, yeah? We’ll see about that!” Which is how Glenn Youngkin carried the college town of Ashland, for example.

Could the same thing happen in Oregon? Greater Idaho says that, with 79 percent of the State’s voters in solid “blue” Northwestern Oregon, the answer is no. (But they might be wrong! The New York Times suggests a Republican might become Governor there.)

The Great Sortation will largely be a movement of—movement, as in moving out. But Oregon could turn into a flash point in a debate that touches on the meaning of land ownership in America, as well as yet another rural-urban divide.

Except for one thing. Liberals tend not to reproduce as fast as conservatives do. One or two generations might then suffice to “flip” Oregon. Or if a Republican does win, he can start by addressing the kind of discontent that would drive people to consider interstate secession.

Link to:

The article:

https://cnav.news/2022/10/23/foundation/constitution/interstate-secession-new-movement/

Greater Idaho home:

https://www.greateridaho.org/

Greater Idaho map:

https://www.greateridaho.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/counties-that-voted-in-favor-of-greater-idaho-11-for-black-backgrounds-uncompact-768x549.png

Conservative News and Views:

https://cnav.news/

The CNAV Store:

https://cnav.store/

Our Silver Lines

https://oursilverlines.com/

-

23:08

23:08

Declarations of Truth

4 months agoMeasurement and American patriotism

2391 -

LIVE

LIVE

Nerdrotic

13 hours ago $3.35 earnedWarner Bros Fire Sale! | Last Ronin CANNED | WICKED For Good REVIEW - Friday Night Tights 381

1,609 watching -

1:35:41

1:35:41

vivafrei

4 hours agoDemonizing Nick Fuentes into the Mainstream! Live with Jake Lang! Miranda Divine Guest & MORE!

64.4K53 -

5:13

5:13

Buddy Brown

7 hours ago $1.37 earnedMuslim PATROL CARS Begin Monitoring NYC! | Buddy Brown

2.63K9 -

12:54

12:54

MetatronGaming

3 hours agoYou Remember Super Mario WRONG and I can Prove it

10.7K5 -

1:02:55

1:02:55

Russell Brand

4 hours agoThe Epstein Files Are Coming — And The Establishment Is Terrified! - SF653

81.7K14 -

32:47

32:47

The White House

3 hours agoPresident Trump Meets with Zohran Mamdani, Mayor-Elect, New York City

22.4K54 -

1:07:21

1:07:21

The Quartering

2 hours agoPeace Between Ukraine & Russia? Kimmel Meltdown & More layoffs

27.8K13 -

LIVE

LIVE

Barry Cunningham

3 hours agoBREAKING NEWS: PRESIDENT TRUMP MEETS WITH COMMIE MAMDANI | AND MORE NEWS!

1,184 watching -

LIVE

LIVE

LadyDesireeMusic

2 hours ago $1.14 earnedLive Piano Music & Convo | Anti Brain Rot | Make Ladies Great Again | White Pill of the Day

103 watching