The Constitution And Elections Explained

On February 1st Mark Levin explained elections and judicial review stated in Marbury versus Madison.

Segment 1

I have been listening to people pile on on this issue of January six and whether the vice president, the United States, Mike Pence, had the authority to reject or to send back to various states. There are elector counts, the snideness, the self aggrandizement of those who insist he had no authority whatsoever from former federal prosecutors to reprobates with a computer is really quite remarkable. And so I want to circle back on this question. Because they are 100 percent certain he did not I’m not advocating anything, I’m not a special pleader for anything, but we’re going to look at this and we’re going to look at it without the blinding hate for Trump at National Review, for The Wall Street Journal or these other places. I think for myself. I study these things myself, the Constitution, the Federalist Papers, Madison’s notes. The state conventions, all that I’ve studied my entire life, say nothing about this topic zero. So they point to a statute that was passed about 150 years ago by Congress that lays out a process that is to take place as their authority. Well, I look at the Constitution as my authority. But before we get there, I have a question for you. It all makes sense when I’m done. So you get to stay the whole hour. Is the phrase judicial review anywhere in the United States Constitution? Anywhere. Under Article three. When the framers wrote Article three and said very little. About the court, they created the Supreme Court, other than in the Federalist Papers, Hamilton said it would be the least dangerous of the branches of government. Where they promoting this idea of judicial review? That the court would have the final say. On the interpretation of the Constitution of the United States, where is that in the Constitution, Mr. Producer? Nowhere. It is an implied power. And yet, if you defy a court and you’ve heard me say it. He could be held in contempt of court. The court has overridden. Statutes, federal statutes, it’s overridden Congress, it’s overridden a president where all the power come from. The court assumed this power. Starting with a case. Called Marbury vs. Madison, a very famous case, you may have heard about it, and it’s been roundly celebrated from the ACLU to the Federalist Society many years ago when I wrote my first book, Men in Black Eye, I condemn this decision. Thomas Jefferson, in a letter to Edward Livingston in 1825, said this member of the government was at first considered as the most harmless and helpless of all its organs. But it has proved that the power of declaring what the law is by sapping and mining slyly without alarm, the foundations of the Constitution can do what open force would not dare to attempt. So how did America reach the point I wrote with a federal judiciary has amassed more influence over more areas of modern life than any other branch of the government, from which section of the constitution with the courts, granted the authority to overrule Congress and the president? The answer is that the Supreme Court has simply taken such power for itself. Nowhere in the Constitution is the federal judiciary expressly given the authority to interject itself in every facet of federal and state operation. Federal courts have accumulated their power under the rubric of judicial review. Judicial review involves a court overturning an act of Congress or the executive branch on the grounds that the act in question contravenes the federal constitution. It is founded on the principle that courts will be unbiased guardians of the clear meaning of the Constitution. At the time of the Constitutional Convention in 1787, there were only a handful of instances in which state courts overruled legislatures for violating state constitutions. Moreover, state courts did not assume carte blanche authority to rule on any subject. The courts followed British common law. They ruled on criminal law, matters of equity between individuals and businesses and other legal matters. Courts also, as a rule, regarded the state constitutions as the central legal nervous system of the respective states. Because the constitution of a state had been adopted by the people generally through a convention and or direct popular vote, it was considered by judges to be a higher law than an act of the legislature or a state governor. The Virginia Constitution of 1776 even included a statement of principles that, quote, all power of suspending laws or the execution of laws by any authority without consent of the representatives of the people is injurious to their rights and ought not to be exercised, unquote. There was no mechanism in the Articles of Confederation, the forerunner to the Constitution, for the sort of sweeping judicial authority later assumed by federal courts, the articles, in fact, didn’t establish a permanent federal judiciary but relied on state courts to resolve disputes. Most delegates at the Constitutional Convention in 1787 thought a federal court system was necessary, that the federal judiciary should be independent of and not subordinate to the other branches of government. That principle was affirmed in nearly every state constitution and that federal judges should serve during good behavior, essentially for life. These state constitutions aimed to insulate judges from political pressure. But every state constitution explicitly allowed judges to be impeached as a check on misbehavior. In other words, judges were expected to be accountable to the Constitution and the people who approved it. The first mention of the judiciary in the Virginia plan, which served as the initial outline for the constitutional convention, was to make it part of a council of revision that would examine acts of the national legislature and approve or reject them. The Congress could pass a bill over the council’s veto beyond its role in the Council of Revision. The Virginia plan had the federal judiciary consisting of a supreme tribunal and inferior tribunals as designated by the legislature. The inferior tribunals will be arbiters of fact, while the Supreme Tribunal would be the final Court of Appeal, the jurisdiction for the judiciary was also specific. Quote, All piracies and felonies on the high seas captures from an enemy cases in which foreigners are citizens of other states applying to such jurisdictions may be interested or which respect the collection of the national revenue impeachments of any national officers and questions which may involve national peace and harmony. Within days of the Constitutional Convention beginning its work on June four, 1787, the delegates took up the question of the court’s participation in this council of revision, and there was substantial opposition to it. Few delegates spoke in favor of the concept, and there were many questions about the judiciary maintaining its objectivity. If we were involved in negating legislative acts. The convention had its most focused exchange on the topic of judicial authority on August 15, 1787, again taking up the issue of judicial veto over acts of Congress. The debate began with. James Madison, quote, moved all that, all acts before they become law should be submitted both to the executive and Supreme Judiciary departments, that if either of these should object two thirds of each house, if both object, three fourths of each house should be necessary to overrule the objections he’d give to the act and give the ax the force of law. Charles Pickering of South Carolina opposed the inference of the judges in the legislative business. It will involve them in parties and give a previous tenure to their opinions. John Dickinson of Delaware argued that judges should not be empowered to overturn acts of national legislature. Roger Sherman of Connecticut, that would be Dickinson of Pennsylvania, disapprove the judge’s meddling in politics and parties. The framers considered and rejected the inclusion of the judiciary in the review process. They didn’t want judges involved in either the legislative process with all the political intrigue that would entail or reviewing laws they would eventually have to adjudicate. Hugh Williamson, a delegate from North Carolina, noted that he preferred to give the power to the president alone rather than admitting the judges into the business of legislation. Ultimately, the convention came up with the presidential veto. But most important, the framers did not intend to grant general authority to the judiciary to rule on the constitutionality of legislative acts. Madison, who by August 27 had dropped his initial support for the judiciary being involved in a veto, summed up the convention’s take on judicial review. He wrote he doubted whether it was not whether it was not going too far to extend the jurisdiction of the court. Generally, the cases arising under the Constitution and whether it ought not be limited to cases of a judiciary nature. The right of expounding the Constitution in cases not of this nature ought not be given to that department. The final analysis, the framers had wanted to empower the judiciary with a legislative veto, they could have done it, they didn’t. Instead, the convention crafted a judiciary, like many other provisions in the final constitution as a product, a compromise. It was a compromise between the interests of the individual states and the need for a federal government that would be strong enough, flexible enough to meet the present and future needs of the nation with a diverse interest was also the clear intention of the framers that no one branch would be submitted excuse me, subsumed by the other. And once the convention completed its work, the battle began over the proposed constitution. Is this boring, everyone you think, Mr. Madison, the Federalist Papers, authored by Hamilton, Madison and Jay were among the first and the best postrevolutionary war examples of American campaign literature. There are a series of 85 essays that began appearing in the New York newspapers as little more than a month after the Constitutional Convention ended on September 17, 1787, written to persuade members of Congress and the states to adopt it as, say, 78 to 83, all written by Hamilton, contain the principal discussions of the nature and authority of this new judiciary because there was no federal judiciary in existence at the time and the principal concern was protecting the judiciary from being subsumed by the seemingly more powerful executive and legislative branches. Much of the debate centered on creating an independent judiciary rather than in limiting the scope and authority of federal judges. It’s for this reason that much of Hamilton’s effort in Federalist 78 was dedicated to an explanation of the steps taken by the framers of the new constitution to ensure that the federal judges would be independent and free of control from Congress. The president, the political whims of the day in the various state legislatures. The judiciary did not represent a threat, Hamilton wrote, quote, So long as the judiciary remains truly distinct from both the legislative and executive fray agree that there is no. Liberty, if the power of judging be not separated from the legislative and executive powers. This is exactly what has happened. But in reverse, instead of being subsumed by Congress of the president’s judiciary, has subsumed substantial authority over the other branches. While other issues guarded most of the attention in the ratification process, there were commentators on both sides of the debate who addressed the nature and potential problems that could develop in the federal judiciary. Unquestionably, spokesmen such as Hamilton, Madison and GAO were very persuasive as pro constitution voices. But there were also forceful opponents of the Constitution who saw the potential abuses. Robert Yates, an ardent anti federalist delegate to the convention from New York, was an especially articulate opponent of the Constitution, and he wrote a series of essays in the New York Journal, which became known as the Anti Federalist Papers, and he wrote under the name Brutus. And when we come back, I want you to know what he had to say about this whole issue of the judiciary and judicial review, and I will get to the point. What does all of this have to do? What, January six? I’ll be right back.

Segment 2

I’m going to need every minute of this hour to get through this, but stick with me, Robert Yates or Brutus in the Federalist Papers. He said the real effect of this system of the judiciary of government will therefore be brought home to the feelings of the people through the medium of the judicial power. It is, moreover, of great importance to examine what care the nature and extent of the judicial power, because those who are to be vested with it are to be placed in a situation altogether unprecedented in a free country. They are to be rendered totally independent. Both of the people and the legislature, both with respect to their offices and salaries. No errors they may commit can be corrected by any power above them if any such power there be. Nor can they be removed from office for making ever so many erroneous adjudications. The only causes for which they can be displaced is conviction of treason, bribery and high crimes and misdemeanors. This part of the plan is so modeled as to authorize the courts not only to carry into execution the powers expressly given, but where there are wanting or ambiguity expressed to supply what is one thing by their own decisions. Now, I’ve got more on this. The goal here is not to reargue Marbury vs. Madison, but to use it, to use it. Stick with me. I know it’s a little high brow, but stick with me. I’m going to pull it back to January six at the end of this hour. Stay with.

Segment 3

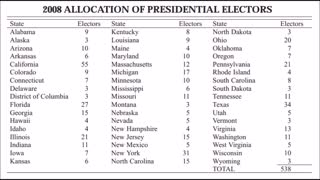

OK, folks, on March eight eight, 02, just days after Thomas Jefferson’s followers, the Republicans took control of both houses of Congress because Jefferson had won the presidency. Also, Congress repealed the Judiciary Act of eighteen or one. On April 29, 1892, Congress enacted the Judiciary Act of 1802, which, among other things, abolished the six new judgeships created by President Adams and his Federalist Party, C. Adams tried to rush it through as fast as he could. Because of the delay between the election. And Jefferson’s inauguration in 1883, Marbury vs. Madison decision, the Supreme Court determined it had the power to decide cases about the constitutionality of congressional executive actions and when it deemed they violated the Constitution, overturn them. The shorthand label given to this court made authorities judicial review. This, quite literally, is the foundation for the runaway power exercised by the federal courts. To this day, what is far less recognizes that Marbury started out as anything but the ominous precedent it has become. It was a brilliantly conceived political strategy crafted by John Marshall, a master politician. Marshall, the chief justice of the Supreme Court, wrote the decision not to set a revolutionary precedent but to deny the new president, Thomas Jefferson, his longtime political rival, an opportunity to rebuff a Supreme Court controlled by Jefferson’s federalist opponents. This is Levin’s take based on my reading of history, Marbury was precipitated by the election of 1800 in which Jefferson, the incumbent vice president and leader of the Republicans, ran for president against the incumbent president, John Adams, leader of the Federalists. The Federalists controlled both houses of Congress but were torn between the followers of Adams and Alexander Hamilton. Hamilton’s faction withheld its support for Adams re-election bid in 1900, and the race ended in an Electoral College tie between Jefferson and his vice presidential running mate, Aaron Burr. This is what brought us the 12th Amendment, by the way. Adams came in third. The election was then thrown into the House of Representatives, realizing it would not win re-election. Adams moved to solidify his party’s influence on the federal government. The passage of the Judiciary Act of H1N1, creating 16 new federal circuit judgeships, was part of his strategy just prior to leaving office. Adams, selected in the Federalist controlled lame duck Senate, confirmed nominees to fill the posts. Adams turned ran out, however, before John Marshall, who was then secretary of state, could actually deliver the commissions of office to some of the designees. Let me stop there. There is no way Marshall should have even been involved in this decision, as I explained in the book later. It a conflict of interest. He had a conflict of interest, he was the secretary of state who would deliver the commissions for his president and his party that lost Marshall’s successor as secretary of state, James Madison refused to deliver the commissions as Jefferson at Jefferson’s direction. And William Marbury, among others, filed suit in federal court, seeking an order writ of mandamus, directing Madison to deliver him his judgeship as Justice of the Peace as commission. Marshall, long arrival at Jefferson’s Virginia politics, was one of the most articulate leaders in the Federalist Party. Marshall had served in the Virginia state House, the U.S. House of Representatives, and was one of President Adams representatives to France in 1797 and then, of course, secretary of state. He was nominated to be chief justice by President Adams and assumed the post on February four eight, you know, won exactly one month before Adams term ended. So it was appointed and confirmed quickly after Jefferson had won the presidency. With a Republican majority elected to both houses in Congress in 1800, Marshall realized that Jefferson, his Republicans, could denude the Supreme Court of authority and that he is chief justice, would be impeached and removed from office, given the way he was appointed. This is Mark speaking, Marshall understood that in Marberry case, if he ordered Secretary of State Madisen to deliver Marbury’s commission to office, Jefferson would order Madison to ignore the Supreme Court’s writ and the court’s authority would be seriously weakened. Marshall was also concerned that he’d not be seen as protecting the interests of the federalist jurists like Marbury, who had assumed his position as a justice of the peace and had been hearing cases and issuing judgments for a year. Bearing all this mind, Chief Justice Marshall’s decision to Marbury, while upsetting the Constitution’s balance of power and the relationship between the federal government and the states, was a master political stroke. Marshall stated that Marbury, consistent with legal doctrine at the time, had something akin to a property right to the office to which he had been nominated and confirmed. Marshall also said the federal judiciary should be able to issue an order directing the appointment of Arm of Marbury. But because the Constitution did not enumerate such an original right for the Supreme Court. Well, the court was powerless to do it. That Marshall went well beyond the specific issues in the case, he could have ended it right there, but he said that the court had a responsibility to set aside acts of Congress that violate principles enumerated in the Constitution. I don’t have time to read what he said, but it’s here Marshals’ Federalist Party had lost the presidency in Congress, but Marshall was determined to fight back. And so the doctrine of judicial review was born. Yes, the Constitution is indeed the supreme law of the land. But now the court by its own fiat would decide what is or is not constitutional. The Constitution structure, including the balance of power between the three branches, was now disturbed, if not broken. Although Jefferson is claimed by Boehner and dam Democrats as the father of their political party, he was a leading opponent of judicial activism. After Marbury, Jefferson became an even more vocal critic of what he viewed as the overreaching of the judiciary under Marshall’s leadership. To Abigail Adams, John Adams wife Jefferson wrote a year after Marbury, quote, The Constitution meant that its core branches should be checks on each other. But the opinion which gives to the judges the right to decide what laws are constitutional, what not not only for themselves in their own sphere of action, but for the legislature and the executive also in their spheres, would make the judiciary a despotic branch. And it goes on. The Constitution would not have been ratified. It would not have enough votes to ratify nine state. If the assumption of judicial review under Marshall had been explicitly stated in the Constitution itself, there’s no way. Now, what does this have to do with January 6th? The Constitution explicitly says that Article two, Section one, the second paragraph each state shall appoint in such manner as the legislature thereof, may direct a number of electors equal to the whole number of senators and representatives to which the state may be entitled in Congress. This was understood by the states to mean that the legislatures would have the authority to make the determination on how they were selected. Very rarely in the Constitution did the framers reach out and specify a branch within the states. But here it did. The legislature. Not the governor, not a state court, not a board of election. The legislature decides. The United States Supreme Court in 2020, with all this judicial review, power to reach into every cultural issue in the country, every classroom in the country without limit, other than its own limitations that it imposes rarely on itself. Had the. Requirement. To ensure that the. The black letter law, the text of the constitution was upheld. This language is not confusing. It’s not confounding. It’s as clear as night and day, and it was clearly violated in the 2020 election in one state after another, purposely by Democrats and the Democrat Party, by individuals who they hired hit men, litigators like Mark Elias and others who went around the Republican state legislatures in the Republican states, including Republican states with Republican executives who are irrelevant to this process except under law, which I’ll get to in a moment and defied the Constitution. The Supreme Court failed to act. Claiming judicial review. In the past for the last 200 and some years, but in this case, it shows. To duck. That sent the matter to the United States Congress to decide. And so what they do at National Review and elsewhere in. Just picking on them, they go to the Electoral Count Act of 1887, which is an enormously complex. Law, in fact, it is a contradicting law in many respects. Under the 12th Amendment of the Constitution, the vice president, who is the president of the Senate, undertakes the task of opening the electoral certificate. The vice president’s role is limited. Now, both houses can overrule the vice president’s decision to include or exclude votes. The vice president’s role to include or exclude votes can be overruled. By both houses. And if there’s a tie, say, between the house of a state and a Senate of a state, the governor’s certification trumps. According to the statute. According to the statute. Decisions have been made by vice presidents serving as president of the Senate. With respect to the electoral count, 1960, when Richard Nixon, he allowed late final votes to count even though they were against him. And 69, Hubert Humphrey, having run for president, 68, decided he better recuse himself from the count, which is what he did. There have been challenges really since the beginning of our country to elections of presidents and vice presidents. I mean, why did they pass this law in 1887 to begin with? Because of the great battle in 1876. That’s why. Where does Congress have the authority to pass a law like this? Does it have the authority to pass a law like this? Well, setting procedures. For the counting. Do they have the power to exclude the vice president as president of the Senate to have any effective role other than as a secretary administrator, opening envelopes and making pronouncements about what he’s received? What if you’re president of the Senate, your vice president, the United States, and, you know, there’s disputes in states. You know, there’s a constitutional dispute in a state like Pennsylvania. And you, as the president of the Senate and as vice president, you you have an oath to uphold the Constitution to and you read that second paragraph under Article two, Section one, each state shall appoint in such manner as the legislature thereof may direct. Full stop. As the legislature thereof may direct. And, you know, as a matter of fact. That that is not only in dispute that that did not occur. And then you have people arguing. But the electors. We’re selected and sent to the archivist of the United States by the governor. And yet it’s the legislature that’s challenging the governor. We’re told to bad. The vice president of the United States does not have any explicit power under the Constitution to do anything. In fact, we look at the 1887 statute in the way that we interpreted. Is that his role is utterly ministerial. You mean like judicial review? Where is judicial review in the Constitution? Well, somebody has to make the final decision. Well, where’s the president of the Senate’s role? If he or she now knows or believes. That’s some of the electors being sent to the archivist and then to the joint session of Congress. Are in effect, spoiled. Because there’s a dispute between the legislature and the governor, but the governor nonetheless. Signs the accreditation, so when I read articles like Trump’s absurd attack on Pence and these guys, of course, they’re not going to talk about the Constitution, they’re not going to talk about past disputes and challenges. They’re not going to talk about Article two, section one, paragraph two, they’re just going to dismiss Trump. Whether by hook or by crook, Trump has a better understanding than they do. Trump has a better understanding than they do either intuitively or otherwise. Joining the mob. And telling us and telling us something that’s not true because you can’t demonstrate it under the Constitution of the United States, serves no purpose but to mislead the American people. I’ll be right back.

Segment 4

Insurrection, January six. Wolf, there was an insurrection broadly defined, it began well before January 16. The Capitol building wasn’t stormed before January six during the election, of course, but the changes to the laws involved in selecting a president and vice president in many cases were in violation of the federal constitution. That’s very specific. And it was violated by judges. It was violated by governors. It was violated by bureaucrats. It was violated by billionaires. It was violated by local administration, if we’re going to call an insurrection. And the insurrection began long before January 6th. And this is what the pseudo conservatives, the never trump the media and the Marxist left do not want to discuss. They’ll tell you 66 lawsuits. Nobody wanted to hear any. But the judges heard a lot of lawsuits from the Democrats and in most cases upheld the changes in laws. And of course, we have a a brave appellate court in Pennsylvania that just wrote to say, let’s not pretend that things were going to be changed or all changed on January 6th. Things were change long before that. And I want Republican legislatures are trying to fix it. They are accused of acting like Jim. Well, get it, folks. The hell away. I hope that we play this entire hour for family, fans, friends

-

4:25

4:25

Brmomar

1 year agoUS Elections - How do they work?

1 -

4:25

4:25

Ahmedamer94

1 year agoUS Elections - How do they work?

9 -

4:44

4:44

SCSafeElections

8 months agoHow elections are run

3881 -

10:23

10:23

TrustNoMarko

1 year agoAmerican Political System Explained!

4 -

49:56

49:56

Intercessors for America: News.Prayer.Action.

1 year agoConstitutional Corner - The Constitution and Elections

3.87K1 -

4:42

4:42

CGP Grey Archive Channel

11 months agoHow the Electoral College Works

8 -

4:44

4:44

Conspiracy Theory Facts

1 year agoA Constitutional Republic Explained

261 -

5:19

5:19

CGP Grey Archive Channel

11 months agoPrimary Elections Explained

3 -

54:22

54:22

OurLivesandPolitics

5 months agoFree and Equal Elections

76 -

35:48

35:48

Mountain_Patriots

7 months agoWUW #3 - Understanding How We Got The Constitution and our Form of Government

108