Premium Only Content

The Filton 24 Just Shattered Britain's Political Prisoner Myth

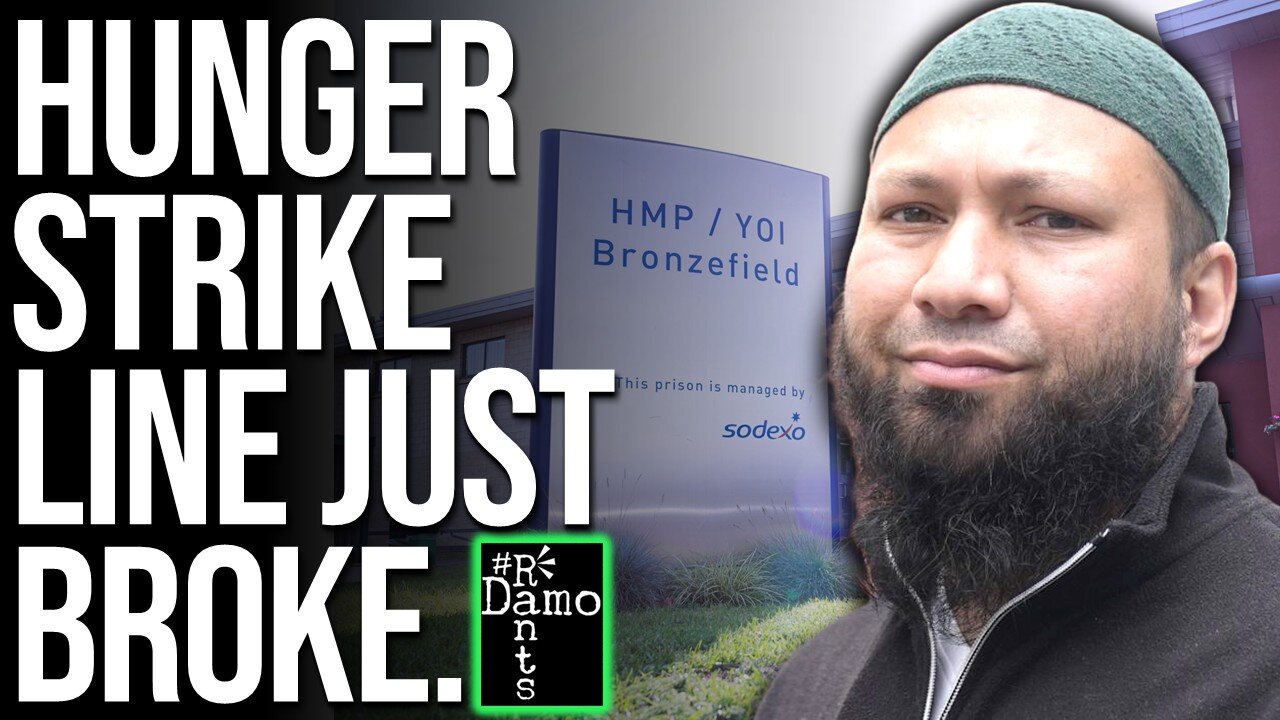

Right, so you look at the state of Britain in 2025 and you realise we’ve reached the point where people are starving themselves in prison just to be heard now, and the government still acts like they’re a filing error, actually acting with casual indifference in my view, since they’ve done nothing about it. Six hunger strikers on remand, at least one hospitalised, trials drifting into next year, and the political class can’t even pretend to care. We are of course talking about six members of the Filton 24, this is how the government treats protesters taking their action to the doorstep of an Israeli arms firm after it dresses them up in the language of terror. They treat them like an administrative inconvenience, which tells you everything about who this system is built to serve. And then along comes Mothin Ali, the deputy leader of the Greens, walking into Bronzefield prison to visit these political prisoners as he has called them and I don’t disagree, because nobody else in Westminster dares open the door, and suddenly the whole thing looks as political as it always was. If you want to understand how power works here, you start with the people the state hopes you never notice.

Right, so this is what’s happening, and I’ll say it plainly because the state won’t: a group of people are in prison on remand, some for more than a year, not because the courts have found them guilty of anything, not because a jury weighed evidence and reached a verdict, not because the law demanded it, but because in my view the government finds their politics inconvenient and the justice system has quietly allowed the line between protest and extremism to blur until that distinction barely exists. They are the Filton 24, although not all are held in the same place and not all are on hunger strike, and their story tells you more about the real state of civil liberties in Britain than any speech, manifesto or ministerial press conference. And if that sounds like a heavy opening, good, because this is a heavy story and it should feel heavy. It should sit in your chest like a stone because this is one of those moments where you can see the machinery of power working in the open, not hiding, not apologising, just grinding on as if this is all normal.

You have people charged with criminal offences linked to direct action at a weapons factory, a place tied into a wider international supply chain feeding wars many of us have watched in horror. You have prosecutors dropping words like “terrorism connection” into court while never actually charging these people under terrorism law, which is always a tell, because if the evidence existed to make the charge stick, they’d use it. Instead they use the insinuation, because insinuation is a useful weapon. You say “terrorism-adjacent” often enough and the legal system starts behaving as if terrorism has actually been committed, even when the paperwork says otherwise. And the effect is the same: bail denied, remand extended, rights restricted, conditions tightened, contact with the outside world curtailed. You create a shadow state where the detainee becomes someone the system treats as a threat without having to prove anything.

That’s where the hunger strike comes in. And if you’ve never watched a hunger strike unfold, this is the point where the state pretends the prisoner is doing it to themselves. They talk about “choice” and “risk” and “duty of care,” but the truth is hunger strikes only happen when every other avenue has been shut down. You don’t starve yourself because you think it’ll be good PR. You do it because the system has made it clear it will not acknowledge your existence in any other way. The Filton hunger strikers didn’t begin on a whim. They began because they had been denied contact, denied updates, denied basic fairness, denied the right to know what their supposed legal future even looked like. They began because nothing else worked.

And once the hunger strike starts, you can track the decline. Fainting. Vomiting. Ketones climbing. Blood sugar crashing. Hospitalisation. A body shutting down in real time because the state has decided your voice doesn’t matter and you’ve decided your body is the only tool you have left. It’s a horrible dynamic. It’s also one of the clearest tests of whether a government respects human rights or simply pays lip service to them. Because no government that actually respects civil liberties allows hunger strikers to reach this point. A government that respects civil liberties intervenes, negotiates, proves it has nothing to hide. A government that fears scrutiny doesn’t.

And that’s where the political silence becomes the loudest part of the story. Because where is everybody? Where is the opposition? Where is the party that insists on calling itself the moral centre of British politics? Labour under Starmer has made a choice: don’t touch this. Don’t mention the Filton 24. Don’t question the judicial process. Don’t criticise the CPS. Don’t ask why people are rotting on remand for a year in a non-terror case. Don’t visit the prisons. Don’t show interest. Just pretend this isn’t happening.

And you can see why they do it. Because the moment they acknowledge the hunger strike, they have to answer questions about the counter-extremism framework they’ve been leaning into. They have to talk about the plans to potentially proscribe activist groups. They have to talk about how they’ve backed the government’s own extremism definition. They have to discuss the uncomfortable fact that Britain maintains deep ties with a weapons manufacturer linked to a foreign state whose military operations have triggered global outrage. They have to clarify why activism against that company has suddenly been treated as something approaching subversion. They don’t want that conversation. So they pretend none of it is happening.

The Conservatives don’t have to pretend anything. They built the machine. They set the tone. Their silence is maintenance. The Lib Dems, predictably, vanish whenever an issue becomes too serious to grandstand about. The SNP has said little. Plaid, nothing. None of them will walk into Bronzefield Prison and look a hunger striker in the face. None of them will put their name to a demand for bail. None of them will risk being called soft on “extremism.” Because the trap here is obvious: the state floats the language, and anyone who challenges it becomes “suspicious.” And the political class, terrified of losing their status as “responsible adults,” swallows the whole framework rather than question it.

Which leaves one figure in this story to talk about therefore: the deputy leader of the Greens, Mothin Ali. He went into the prison. He met them. He listened. And he’s spoken out since. He’s spoken of Amu Gib who has been on hunger strike for 32 days, with her cheekbones sticking out and her eyes sunken in. He’s spoken about Qesser Zuhrah who at just 20 years old is suffering from low blood pressure but a high heart rate – very dangerous – where her own doctors are saying she needs hospital treatment, but the nurses according to Ali won’t let her be moved. He spoke of guards telling Amu she wasn’t allowed to sit with her knees crossed despite there being no such rule in place, a deliberate act of humiliation designed to break people.

Mothin Ali didn’t treat them as criminals waiting for punishment but as people in a political struggle against a system that has outgrown accountability. And he said something no other politician dared to say: these are political prisoners. He broke the line. He broke the script. He said what the rest of them refuse to say out loud because saying it out loud forces a confrontation with everything they’ve allowed to slide.

This is where matters shift up a gear, because now we’re not just talking about activism or protest or hunger strikes. Now we’re talking about the transformation of Britain’s legal and political order — a shift where the police, the CPS, the courts and the government operate as a single ecosystem when certain kinds of dissent emerge. You’ve seen versions of this before with environmental activists. You’ve seen it with anti-fracking protesters. You’ve seen it with policing of marches. But the Filton 24 sit at the edge of something new, where counter-terror logic and political suppression merge into one tool.

And if you want to understand the scale of that shift, look at the response to a weapons factory protest. Not a bombing. Not an attack on civilians. A protest at a facility tied into international arms infrastructure. And what does the state do? It drags activists into a holding pattern where time becomes the punishment. It restricts their communication. It leaves them there long enough for a hunger strike to become a rational decision. That’s not justice. That’s not procedure. That’s the state making an example.

And the reason they’re comfortable doing it is simple: they don’t think you’ll care. They assume the silence will hold. They assume nobody will break ranks. They assume the political class will look away. That’s why the deputy leader of the Greens stepping into a prison matters. Not because he holds numerical power. But because he breaks the collective neutrality. He disrupts the choreography. He refuses to let the state manage this through invisibility and he positions the Greens as being very different on such things, as frankly we should all want, because this is a disgrace.

And that raises the real question: what happens when silence is no longer enough for the government to maintain control of the narrative? What happens when an elected politician uses their platform to drag the story into the open? What happens when the question becomes unavoidable and more people start asking it as Mothin Ali has done: why is Britain holding political prisoners?

And yes, that’s the phrase, because once you strip away the bureaucracy, once you take out the procedural niceties, once you collapse the euphemisms that politicians hide behind, not to mention the nonsense they’ve made of UK terror law, you’re left with the blunt reality that people are being held by the state for political reasons. They are not being held because they pose an ongoing threat. They are not being held because the evidence against them is overwhelming. They are being held because their activism targets a part of Britain’s foreign policy architecture that is not supposed to be touched. That’s political imprisonment. The truth is clearer than the politicians would dare to admit.

And it becomes even clearer when you look at the way the hunger strike is handled. You would think that a modern democracy, confronted with a coordinated hunger strike by prisoners who haven’t been convicted of anything, would treat it as a crisis. You would think ministers would be on camera insisting that conditions will be investigated, that remand decisions will be reviewed, that the system will address legitimate grievances. Instead, the silence is absolute. You get phrases like “monitoring the situation” and “duty of care,” but you never get the thing that matters: accountability. The state treats the hunger strike as an internal management issue, not a political event. It treats collapsing bodies as paperwork. That tells you everything.

And the thing about hunger strikes is this: they are a mirror. They force a country to look at itself, and most governments hate mirrors. A hunger strike exposes whatever you’re trying to hide, because there is no way to spin a person starving themselves. You either engage with their demands or you pretend the starvation isn’t happening. And pretending it isn’t happening is the choice of a government that already knows it is in the wrong. A government that thinks it is in the right addresses the grievance. A government that knows the grievance points to a deeper rot tries to bury the whole thing.

Now, zoom out and look at the larger political architecture, because this isn’t just about a prison or a trial or twenty-odd activists. This sits inside a wider shift across Britain where protest rights have been carved away bit by bit under the excuse of maintaining “order.” You’ve got a counter-extremism framework so vague it can be pointed at anyone the government finds inconvenient. You’ve got attempts to classify activists as national security threats. You’ve got a political climate where solidarity with victims of foreign wars is treated as destabilising. You’ve got a policing culture that is rewarded for shutting down dissent rather than facilitating it. None of this is accidental. The state is not confused about its priorities. It knows exactly what it is doing.

And when Labour stays quiet, it’s not because they disagree with the repression and don’t know how to say so. It’s because they agree with the repression and know exactly why they won’t say so. They have positioned themselves as guardians of stability, guardians of “responsible governance,” guardians of a political centre that treats any challenge to Britain’s military or foreign policy establishment as vaguely subversive. So of course they won’t speak. They don’t want to be associated with “extremism.” They don’t want to anger allies abroad. They don’t want to risk being framed as anti-industry or anti-security. In effect, they have become a second governing party rather than a counter-balance to power.

And this is where we get to the real heart of the matter: the Filton 24 aren’t just dealing with a justice system acting strangely; they are dealing with a political class that has tacitly agreed to treat them as expendable. When no major party steps up, when no official opposition asks questions, when no MP visits the hospitalised striker, you’re left with a clear map of power. And on that map the activists sit at the very bottom. They have no institutional protection. They have no political patronage. Their cause is inconvenient, their methods are confrontational, and the people they challenge are wealthy, globally connected and shielded by the state.

Now contrast that silence with what happens when a weapons company feels threatened. Suddenly, urgent statements appear. Suddenly, there are calls for national security reviews. Suddenly, there’s talk of protecting “critical industries.” The state comes alive when property is damaged, but not when people starve. That tells you what is valued: not life, not justice, not democracy, but the infrastructure of power itself.

And so when Mothin Ali walks into a prison and sits down with hunger strikers, that is a direct challenge to the hierarchy. That is stepping into a space the major parties abandoned. That is saying: the line between justice and punishment must be redrawn. And it forces a reckoning, because if a smaller party can do what Labour refuses to do, it raises a question the establishment hates: what is Labour for? If not to defend civil liberties, if not to question the state’s excesses, if not to protect the vulnerable from political overreach, then what exactly is its purpose?

You can feel the tension this creates. The hunger strike becomes more visible. The prison system is forced to account for decisions it hoped nobody would scrutinise. The government has to contend with a narrative that no longer frames these detainees as faceless agitators but as people locked inside a political struggle. And once that narrative breaks through, control becomes harder for the state to maintain. Because political imprisonment relies on silence. It relies on invisibility. It relies on people not knowing or not caring. You break that, you break the mechanism.

And if you want to understand the stakes, consider how quickly this could escalate. Hunger strikes don’t plateau. They decline. They intensify. They break bodies. They risk death. And a death in custody, on remand, in a politically charged case, would be a scandal no government could bury. It would force answers. It would force inquiries. It would force ministers onto camera explaining why a detainee died before they were even tried. The state knows this. That is why the silence is so rigid. They hope the hunger strike ends before the questions start. They hope the cracks stay small.

But the cracks are widening. Because once you understand that political prisoners aren’t something that happens “over there,” in dictatorships, in failed states, but right here in Britain as has been identified both by a politician and in print, under the watch of a government that claims moral leadership, you start asking more dangerous questions. You start asking what other groups could be next. Environmental activists. Anti-war protesters. Whistleblowers. Anyone who embarrasses a powerful company. Anyone who challenges the strategic alliances Britain is determined to maintain. Power expands unless it is stopped. And right now there is almost nothing stopping it.

That’s what all of this is ultimately about. Not just the hunger strike, not just the remand conditions, not just the contradictions in the legal process. It is about whether Britain is quietly normalising political imprisonment under the cover of security language. It is about whether the justice system is being reshaped to protect the powerful and deter dissent. It is about whether the political class has abandoned civil liberties altogether in favour of corporate-state alignment. And it is about whether the public will accept that shift or fight it.

Britain is holding political prisoners, and only one national political voice has had the courage to say so. Mothin Ali of the Greens. The silence of everyone else isn’t accidental — it’s ideological. And the longer we pretend this is normal, the quicker we lose the right to protest at all.

This is of course one more example of the Green Party owning the Home Office through the optics, and the Home Office has of course tried pushing back on such things, having tried it on with the other Green Deputy Rachel Millward, but when you dig into the detail, once again it doesn’t stand up, so get all the details of that story here.

Please do also hit like, share and subscribe if you haven’t done so already so as to ensure you don’t miss out on all new daily content as well as spreading the word and helping to support the channel at the same time which is very much appreciated, holding power to account for ordinary working class people and I will hopefully catch you on the next one. Cheers folks.

-

26:18

26:18

GritsGG

14 hours agoHow to Activate Heat Map & Find Self Revives On Warzone!

4.79K -

29:01

29:01

The Pascal Show

1 day ago $8.54 earnedRUNNING SCARED! Candace Owens DESTROYS TPUSA! Are They Backing Out?!

39.6K47 -

24:45

24:45

Blabbering Collector

1 day agoUnboxing The 2025 Diagon Alley Advent Calendar By Carat Shop | Harry Potter

5.77K -

0:43

0:43

Gaming on Rumble

1 day ago $5.65 earnedLvl UP (Raids)

38.9K2 -

19:07

19:07

MetatronGaming

1 day agoWe need to find a way out NOW!

5.88K -

1:11:16

1:11:16

omarelattar

4 days agoHow I Went From Depressed w/ $0 To $500 Million Per Year In My 20's (COMFRT CEO Hudson Leogrande)

6.5K -

2:22:42

2:22:42

Badlands Media

23 hours agoDevolution Power Hour Ep. 413 – The J6 Narrative Cracks, Media Meltdowns, and the Intel Nobody Trusts

229K34 -

7:13:51

7:13:51

MattMorseTV

12 hours ago $94.15 earned🔴THE STREAMER AWARDS🔴

192K57 -

5:50:33

5:50:33

Side Scrollers Podcast

17 hours agoSide Scrollers Presents: QUEEN OF THE Wii

113K22 -

2:08:11

2:08:11

TundraTactical

13 hours ago $4.08 earnedMatt Hover (CRS Firearms) Released This Week, Glock Gen 6 is Here, and More Tonight At 9pm CST

21.2K