Face Of Suffering Famine Cholera Wreak Havoc In War Torn World Wide Pandemic ?

A year and a half since the Covid-19 pandemic began, deaths from hunger are outpacing the virus. Ongoing conflict, combined with the economic disruptions of the pandemic and an escalating climate crisis, has deepened poverty and catastrophic food insecurity in the world’s hunger hotspots and established strongholds in new epicenter's of hunger.

The worst is still yet to come unless governments urgently tackle food insecurity and its root causes head on. Today, 11 people are likely dying every minute from acute hunger linked to three lethal Cs: conflict, Covid-19, and the climate crisis. This rate outpaces the current pandemic mortality rate, which is at 7 people per minute.

Governments must focus on funding urgent hunger response and social protection programs to save lives now, rather than striking arms deals that perpetuate conflict, war and hunger. As equally important as stopping Covid-19 itself, is stopping it from killing more people through hunger. We need action to create fairer, more resilient and sustainable ways of feeding the world. Famines are sustained, extreme shortages of food among discrete populations sufficient to cause high rates of mortality. Signs and symptoms of prolonged food deprivation include loss of fat and subcutaneous tissue, depression, apathy, and weakness, which progress to immobility and death of the individual, often from superimposed respiratory or other infections. The social consequences of famines are disruption from mass migrations of people in search of food, breakdown of social behavior, abandonment of cooperative effort, loss of personal pride and sense of family ties, and finally a struggle for individual survival. Famines have been common ever since the development of agriculture made human settlements possible. Food shortages due to crop failures caused by natural disasters including poor weather, insect plagues, and plant diseases; crop destruction due to warfare; and enforced starvation as a political tool are by no means the only causative factors. Many of the worst famines have been due to poor distribution of existing food supplies, either because of inequities that result in a lack of purchasing power on the part of the poor or because of political interference with normal distribution or relief movements of food. Europe and Asia, which in the past experienced frequent severe famines, sometimes with deaths in the hundreds of thousands or millions, have now largely eliminated famines through social and technological change. However, in Africa, political and social factors have destroyed the capacity of many populations to survive drought-induced variations in local food supplies and prices. Thus, famines are due to varying combinations of inadequacy of food supplies for whatever reason and the inability of populations to acquire food because of poverty, civil disturbances, or political interference. Despite the role of natural causes, the conclusion is inescapable that modern famines, like most of those in history, are man-made.

PIP: Famines are sustained, extreme shortages of food among discrete populations sufficient to cause high rates of mortality. Crop failures caused by natural disasters including poor weather, insect plagues, and plant diseases; crop destruction due to warfare; and enforced starvation as a political tool are some causative factors of famine. However, modern famines, like most of those throughout history, are manmade. Many of the worst famines have been due to the poor distribution of existing food supplies, either because of inequities which result in a lack of purchasing power among the poor or because of political interference with the normal distribution or relief movements of food. Europe and Asia used to experience frequent severe famines, but have employed social and technological change to largely eliminate them. Political and social factors in Africa, however, have destroyed the capacity of many populations to survive drought-induced variations in local food supplies and prices.

A perfect storm has been brewing in Yemen. Along with air strikes that have obliterated cities to rubble, millions of homeless civilians suffering from famine and a tangled political climate, Yemen is also on the verge of the plague. The country’s cholera outbreak, which began in October 2016 with just 11 reported cases, has now infected 500,000 people, according to an August 2017 report from the World Health Organization (WHO). The widespread filth and contamination on the streets and the lack of medicine, hospitals, and doctors has exacerbated the spread of cholera: a disease that is treatable for more than 99% of people who have access to health services, according to the WHO. However, thousands of ill Yemeni people have received no such aid. According to a UN report, nearly 2,000 people in Yemen have died from cholera.

Although the UN has attempted to fund forms of relief, the organization has found difficulties allocating the budget for cholera. Along with the spread of cholera, an estimated 17 million people are suffering from famine in Yemen, affecting 2.2 million children, according to a UN report released earlier this year. As the population of malnourished people accumulates, the outbreak of cholera has become more apparent. The UN called for more funds from international organizations to combat both famine and cholera, but neither budgets have been met. According to the UN, the organization only received $47 million of the $250 million proposed to aid Yemen’s cholera outbreak and raised just one-third of the $2.1 billion needed to supply food for the millions of Yemenis experiencing famine. Overall, the UN’s Yemen Humanitarian Response Plan is only 40.5% funded.

While plans to treat the disease have been in jeopardy, the efforts to prevent the spread of cholera may cease. A spokesperson from the WHO said the organization paused plans to ship cholera vaccines to Yemen because efforts to combat cholera in other countries may be more effective. The shortage of vaccines in Yemen could multiply the number of people affected by the disease. Cholera, which is often spread by poor hygiene and contaminated drinking water, can impact people in Yemen because the country has scarce clean water resources. According to UNICEF, 19.3 million Yemeni people do not have access to clean drinking water and sanitation. Along with vaccines, other gaps in medical aid have become more necessary. In medical facilities across the country, the lack of funds has hit the epidemic’s most needed resource: health workers. The 300,000 health workers who have been treating cholera in Yemen have not been paid for nearly a year, according to a report from the UN.

For the millions of Yemeni civilians, cholera is just one more way people die every day. If not by cholera, a Yemeni could die from gunfire or a landmine on the streets in the capital city of Sanaa, from suicide bombing in the southern city of Aden, from an air strike throughout Yemen’s northern providence, or simply from no access to food in weeks. The civilian death toll in Yemen has reached 10,000 as of January 2017.

The UN has attributed the death to the key political players in Yemen’s civil war and have called on negotiations to stop the rising death rate.

“The Yemeni people need the parties to commit to political dialogue, or this man-made crisis will never end. In the meantime, together we can—we must—avert this famine, this human catastrophe,” said UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs emergency coordinator Stephen O’Brien in a statement in March 2017.

The Yemeni civil war, which has devastated the country for two years, began after the Houthi rebel group attempted to take over the country in March 2015. After the Houthi rebel group and its governing force, the Supreme Political Council reigned control over the northern provinces of Yemen and its capital, the Yemeni government allied with a Saudi-Arabian led coalition to reinstate its power. The political players, which include an alliance between the Houthis, Iran, and Syria and an alliance between the Saudi-led coalition and the U.S., have made the conflict more difficult to soothe over.

In 2017, the U.S. multiplied its airstrikes in Yemen from the year before. In January, the U.S. Navy Seal team launched air strikes and led a raid that killed 30 civilians. In March, U.S. President Trump ordered 40 airstrikes over a five-day period.

With the continuation of airstrikes and raids in Yemen, humanitarian groups have faced difficulty reaching Yemeni civilians. As political entities grapple for power, the absence of a governing body has prevented funds for food and medical supplies needed to stop famine and cholera in its tracks. With the disease escalating to nearly half a million people, the UN has requested international aid for Yemen’s humanitarian crisis.

In an August UN Security Council meeting, officials called on worldwide organizations and countries to advocate for a political resolution under humanitarian and human rights laws.

“Death looms for Yemenis by air, land and sea,” said Ismail Ould Cheikh Ahmed, UN Special Envoy for Yemen. “Those who survived cholera will continue to suffer the consequences of 'political cholera' that infects Yemen and continues to obstruct the road towards peace.”

UNOHC emergency coordinator O’Brien elaborated that although the situation in Yemen is desperate, a solution is possible. “This human tragedy is deliberate and wanton—it is political and, with will and with courage which are both in short supply, it is stoppable,” said O’Brien.

A new Oxfam report today says that as many as 11 people are likely dying of hunger and malnutrition each minute. This is more than the current global death rate of COVID-19, which is around seven people per minute.

The report, "The Hunger Virus Multiplies" says that conflict remains the primary cause of hunger since the pandemic, pushing over half a million people into famine-like conditions ―a six-fold increase since 2020.

Overall, 155 million people around the world are now living in crisis levels of food insecurity or worse – that is 20 million more than last year. Around two out of every three of these people are going hungry primarily because their country is in war and conflict.

The report also describes the massive impact that economic shocks, particularly worsened by the coronavirus pandemic, along with the worsening climate crisis, have had in pushing tens of millions more people into hunger. Mass unemployment and severely disrupted food production have led to a 40 percent surge in global food prices - the highest rise in over a decade.

Oxfam’s Executive Director Gabriela Bucher said: “Today, unrelenting conflict on top of the COVID-19 economic fallout, and a worsening climate crisis, has pushed more than 520,000 people to the brink of starvation. Instead of battling the pandemic, warring parties fought each other, too often landing the last blow to millions already battered by weather disasters and economic shocks.”

Despite the pandemic, global military spending rose by $51 billion - enough to cover six and a half times what the UN says it needs to stop people going hungry. Meanwhile, conflict and violence have led to the highest ever number of internal displacement, forcing 48 million people to flee their homes at the end of 2020.

“Starvation continues to be used as a weapon of war, depriving civilians of food and water and impeding humanitarian relief. People can’t live safely, or find food, when their markets are being bombed and crops and livestock destroyed.”

Bahjah, a mother of eight from Hajjah governorate in Yemen, who had to flee multiple times, told Oxfam: “My husband is very old to work, and I am sick. We had no choice but to send our children to ask people for food or collect leftovers from restaurants. Even the food they managed to collect was not enough.”

Bucher said: “The pandemic has also laid bare the deep inequality in our world. The wealth of the 10 richest people – nine of whom are men - increased by $413 billion last year. This is 11 times more than what the UN says is needed for its entire global humanitarian assistance.”

Some of the world’s worst hunger hotspots, including Afghanistan, Ethiopia, South Sudan, Syria, and Yemen continue to be battered by conflict, and have witnessed a surge in extreme levels of hunger since last year.

More than 350,000 people in Ethiopia's Tigray region are experiencing famine-like conditions according to recent IPC analysis - the largest number recorded since Somalia in 2011 when a quarter-million Somalis died. More than half the population of Yemen are expected to face crisis levels of food insecurity or worse this year.

Hunger has also intensified in emerging epicentres of hunger ―middle-income countries such as India, South Africa, and Brazil― which also saw some of the sharpest rises in COVID-19 infections.

Some examples of the report hunger hotspots include:

Brazil: Measures to curb the spread of virus forced small businesses to close and over half the working Brazilians to lose their jobs. Extreme poverty nearly tripled, from 4.5% to 12.8%, and almost 20 million were pushed to hunger. The federal government secured support only to 38 million vulnerable families, leaving millions without a minimum income.

India: Spiralling COVID-19 infections devastated public health as well as income, particularly for migrant workers and farmers, who were forced to leave their crops in the field to rot. Over 70% of people surveyed in 12 states have downgraded their diet because they could not afford to pay for food. School closures have also deprived 120 million children of their main meal.

Yemen: Blockades, conflict and a fuel crisis have caused staple food prices to more than double since 2016. Humanitarian aid was slashed by half, curtailing humanitarian agencies’ response and cutting food assistance for 5 million people. The number of people experiencing famine-like conditions are expected to almost triple to 47,000 by July 2021.

Sahel: Countries most torn by conflict, such as Burkina Faso, saw more than a 200 percent rise in hunger between 2019 and 2020 - from 687,000 to 2.1 million people. Worsening violence in central Sahel and the Lake Chad Basin forced 5.3 million people to flee and fuelled food inflation to a five year high. The climate crisis worsened the situation: floods have increased by 180% since 2015, devastating crops and hitting the incomes of 1.7 million people.

South Sudan: Ten years since its independence, over 100,000 people are now facing famine-like conditions. Continued violence and flooding disrupted agriculture in the past year and forced 4.2 million people to flee their homes. Less than 20% of the $1.68 billion UN Humanitarian appeal for South Sudan has so far been funded.

Mulu Gebre, 26, who had to flee her hometown in Tigray, Ethiopia while 9 months pregnant, told Oxfam: “I came to Mekele because I heard that food and milk were offered for infants. When I arrived here, I couldn’t find food even for myself. I need food especially for my child, who is now only four months –and already born underweight.”

Bucher said: “Informal workers, women, displaced people and other marginalized groups are hit hardest by conflict and hunger. Women and girls are especially affected, too often eating last and eating least. They face impossible choices, like having to choose between traveling to the market and risking getting physically or sexually assaulted, or watching their families go hungry.”

“Governments must stop conflict from continuing to fuel catastrophic hunger and instead ensure aid agencies reach those in need. Donor governments must immediately and fully fund the UN’s humanitarian appeal to help save lives now. Security Council members must also hold to account all those who use hunger as a weapon of war.”

“To prevent unnecessary deaths and millions more people being pushed to extreme poverty and hunger, governments must stop this deadly disease; a People’s Vaccine has never been more urgent. They must simultaneously build fairer and more sustainable food systems and support social protection programs.”

Since the pandemic began, Oxfam has reached nearly 15 million of the world’s most vulnerable people with food, cash assistance and clean water, as well as with projects to support farmers. We work together with more than 694 partners across 68 countries.

Oxfam aims to reach millions of people over the coming months and is urgently seeking funding to support its programmed across the world.

Yemen is the latest victim of a cholera pandemic that began in 1961, one that could wreak havoc widely for decades to come, says Seth Berkley, CEO of Gavi, the vaccine alliance For six decades, a deadly pandemic has raged, killing millions of people and infecting tens of millions more. Yet because it has been eliminated from wealthy countries barely anyone in the West is aware that it is still ongoing.

Beginning in Indonesia in 1961, the current cholera pandemic – the seventh in modern history – has persisted for six decades. It has its own strain of the bacteria that causes the disease – called El Tor – which has spread to more than 150 countries, sometimes shouldering, sometimes blazing, but never fully extinguished. Almost all of those affected today are the poor and vulnerable in disaster zones or fragile states – think of the outbreak in Haiti in 2010.

The latest flare-up is in Yemen, where at least 1500 people have died and more than 185,000 have been infected amidst war and famine. Sadly, even with a million doses of cholera vaccine on their way to Yemen, things are likely to get worse before they get better.

For the pandemic as a whole, the prospects are also dire.

This is all the more tragic because the disease is as preventable as it is contagious. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that with the right strategy and funding, cholera could be eliminated from most of the world within a few years, to the point that it would no longer pose a global health threat.

Cholera hotspots

Outbreaks can be avoided by improving access to clean water, sanitation and hygiene in cholera hotspots, as well as vaccinating those at risk.

The challenge is that often these hotspots face protracted crises that limit the ability to make improvements, for example in Somalia and South Sudan. In such cases immunization has an even bigger role, provided it can be done early enough.

The good news is that we have safe, effective and affordable vaccines. Before 2011 that wasn’t the case. The only vaccine that met WHO safety and efficacy standards wasn’t suited to developing countries because it needed to be administered using clean water.

But now with support from Gavi, the vaccine alliance I head, this year will see the production of 17 million doses of a vaccine that doesn’t rely on clean water. This will also be used to maintain a global stockpile of 2 million doses for emergency use.

However, in practice, it is hard to get vaccines into crisis zones quickly enough to prevent an epidemic developing. Instead, vaccine use becomes more about control and containment.

Limited sanitation

Epidemics will become more likely, particularly in Africa, where the population is expected to double by 2050 and quadruple by 2100. This, combined with additional pressures from climate change, such as land degradation, rising seas, drought and famine, not to mention conflict, could see tens of millions of people displaced. Inevitably, more will be driven towards cities. In 1950, two-thirds of the world’s population lived in rural areas, and just a third in urban areas. By 2050, this ratio is forecast to be reversed.

More people living in less space, placing more strain on already limited sanitation and drinking water systems, will provide a fertile breeding ground for cholera. At the same time, the sheer scale of modern megacities has the potential to outstrip vaccine supplies, limiting the ability to prevent or respond to outbreaks in this way.

It doesn’t have to be like this. Yemen reinforces a crucial lesson: when it comes to cholera we need to be proactive, not reactive.

When we know there is a very high chance that the disease will appear, we need to vaccinate as soon as possible. To do so, we will need to better understand how the infection initially spreads and which vaccination strategies would be best to prevent this.

In conflict-prone areas this is even more critical, because brief periods of peace may be few and far between. And wherever it is feasible we need to improve access to clean water, hygiene and sanitation. Ultimately, if we don’t want this pandemic to last another six decades then we need to acknowledge it and treat it as a growing threat. Water Crisis

How many of us on Planet Earth lack potable Water?

We are approaching a world in which the one of the most valuable resources for development and survival is not oil, but water.

"A shortage of water resources could spell increased conflicts in the future. Population growth will make the problem worse. So will climate change. As the global economy grows, so will its thirst. Many more conflicts lie just over the horizon." -- Ban Ki-Moon

Water use has grown at more than twice the rate of population increase in the last century.

Globally, 1.2 billion people live in areas with inadequate water supply.

1.6 billion live in areas where there is water, but they can't afford to drink it.

Two-thirds of the cities in China suffer from water shortages. Clean water is even more rare.

India WILL run out of water in the near future.

Is the lack of Water getting better or worse?

Global water demands will increase by 40% in the next ten years.

By 2025, two-thirds of the world will live under conditions of water scarcity.

Water use is increasing much faster than population.

How does the lack of Water affect health and longevity?

People’s who lack sufficient potable water have shorter life spans. Major water borne illnesses abound in parts of the world that lack sufficient potable water. These areas also typically lack adequate sanitation.

How does the lack of water affect geopolitical stability and regional warfare?

It is increasingly recognized that the shortage of potable water is as serious or more serious than the regional problems caused by oil. The CIA has on its public website some 8 years ago stated that within 15 years water would be a source of regional warfare.

Is there enough water on earth to take care of its current 7 billion people (going to 9 billion by 2050)? Yes – 79% of the world’s fresh water is in the form of frozen ice-caps and glaciers in the Arctic and the Antarctic. Groundwater is 20% of freshwater and 1% is accessible surface fresh water. Our shortage is simply a problem of distribution – getting the water to where it is needed when it is needed.

Where is the largest supply of fresh potable water?

In the Antarctic – in the form of tabular icebergs that break off the Antarctic continent and fall into the ocean.

Why don’t we just go get the water and move it to where it is needed?

That is the point – isn’t it.

Can the Antarctic water supply be used economically?

Multiple studies indicate “Yes.” We estimate iceberg water can be delivered at a cost of US $600 to US $1200 per acre foot. Current costs for development and delivery of new desalination water is as high as $2460 per acre foot.

Is using the Antarctic water supply environmentally safe?

Anytime we do anything, it has an environmental effect. Work to date indicates the relative environmental effect is minimal to benign and can be readily mitigated. The environmental effects of all other alternatives to secure equivalent amounts of water are far worse. The environmental effects of doing nothing are worse in terms of human health, death, suffering, and warfare. What is involved in capturing, towing, mooring, and processing Antarctic tabular icebergs?

The Centers for Disease Control has emphasized that washing hands with soap and water is one of the most effective measures we can take in preventing the spread of COVID-19. However, millions of Americans in some of the most vulnerable communities face the prospect of having their water shut off during the lockdowns, according to The Guardian.

Nearly 40 percent of Americans live in areas that rely on water utilities, which have not stopped the policy of shutoffs for non-payment, according to data from and Water Watch (FWW) and The Guardian.

“This is an emergency and the priority is to stop the spread so this is a no brainer, everyone must have access to water … this should not be a partisan issue,” said congresswoman Brenda Lawrence, who is pushing federal intervention, as The Guardian reported.

Millions of Americans have been laid off or furloughed during massive social distancing measures, stretching monthly budgets and forcing families to make tradeoffs about which household expenses to pay for.

“As unemployment reaches record highs, millions of Americans are going to have to choose between paying for food, rent and bills … water is not something people should have to tradeoff,” said Mary Grant, director of water at FWW to The Guardian.

Water shutoffs have affected Detroit for years. Detroit started the policy in 2014 and has recorded about 127,500 total service cutoffs for households behind on payments, according to the water department, as the AP reported. Michigan has the sixth highest total of diagnosed COVID-19 cases in the country.

“In this pandemic, it’s the people who are living on the margins of society and the poorest of our society that’s being the most adversely impacted,” said Rev. Roslyn Bouier, who runs Detroit’s Bright moor Connection Food Pantry, to the AP.

“Access to clean water is a basic human right at all times, but any action that restricts families’ access to water during the current coronavirus outbreak would be reckless in the extreme,” House Energy and Commerce Committee Chair Frank Pallone, D-NJ, and House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee Chair Peter DeFazio, D-OR, said in a statement to the utility companies, as Food Safety News reported.

In Michigan, Gov. Gretchen Whitmer signed an executive order that requires the re-connection of shut off water service. She also started a million grant program to help communities comply with the order, according to WXYZ in Detroit.

“This is a critical step both for the health of families living without a reliable water source, and for slowing the spread of the Coronavirus,” Whitmer said in a release, as WXYZ reported. “We continue to work to provide all Michiganders – regardless of their geography or income level – the tools they need to keep themselves and their communities protected.”

The highest rates of water shutoffs are in southern and rural states, with the large concentrations in Louisiana, Arkansas, Florida and Oklahoma. In New Orleans, which has the fourth highest rate of infections per capita, only 300 homes have been reconnected and the city does not seem to know how many more people are without water, according to The Guardian.

“It’s a package of related factors – institutional racism, environmental injustice, and poverty – which means communities most vulnerable to Covid-19 are the same communities most vulnerable to water shutoffs,” said Grant to The Guardian.

House Democrats proposed a bill that included a .5 billion allocation to help cover water bills for low-income families and also would ban utility shutoffs during the pandemic, according to the AP. Additionally, The Guardian reported that last week, Nancy Pelosi signaled plans to propose billion earmarked for water projects in a forthcoming infrastructure bill to stimulate economic recovery.

Countries That are Most Likely to Run Out of Water in Near Future The news of India experiencing one of the worst droughts in its history is creating a buzz from quite a while now. Such is the situation of water scarcity in India, that the country is almost on the brink of losing all its clean water. As per the Composite Water Management Index (CWMI) report released by the Niti Aayog, it was predicted that 21 Indian cities, including Delhi, Bengaluru, Chennai and Hyderabad, will face Day Zero situation by 2020. And not to be surprised, Chennai has become the first Indian city to have gone dry. For a long stretch of about 200 days, the people of the city lived without a single drop of rain, before it finally arrived on 18 June 2019. But, that’s not enough to bring the city back to a normal situation.

What’s the current situation in India?

For the two consecutive years, the entire country is experiencing weak monsoons. And hence, a quarter of India’s population is affected by a severe drought. For a fact, 12% of the country’s population is already living in a situation where they could be a ‘Day Zero’ situation at any time – thanks to excessive groundwater pumping. The CWMI report also says that the country’s water demand is projected to be twice the available supply by the year 2030.

Well, it’s not just India which is going through such a critical situation. There are other countries as well that are more likely to lose all their drinking water in near future. I have compiled a list of 11 major countries (including India) that are running out of water.

South Africa Water Crisis

South Africa is one of the first countries facing the situation of the water crisis. In January 2018, it was predicted by the officials in one of the main cities of South Africa, Cape Town, the municipal water will run out within three months. The situation was so severe that photos of parched earth dams and locals lining up to collect spring water flashed across the internet and news sites. Like Cape Town, Durban is another South African city which is facing water crisis. The dams in Durban are 20 per cent lower than the start of 2010. There are a number of reasons that contribute to this growing water crisis in South Africa, however, climate change is a major reason of all.

Brazil Water Crisis

Brazil is another country that is going through a similar situation as South Africa. The financial capital of Brazil, São Paulo is one of the most populated cities in the world. The water crisis in São Paulo begun in the year 2015 when the main reservoir of the city fell below 4 percent of the capacity. With a population of 21.7 million, the city was left with only 20 days of water supply. As a result of that, water trucks were looted. Along with that, the water supply to many homes was cut down to just a few hours twice a week. In January 2017, the country’s financial capital again came into the strain of water supply as the main water reserves were below 15 per cent. Even in 2019, the water crisis in Brazil left the country’s five million people without access to clean water.

Jordan Water Crisis

Jordan is the third most water scarce country in the world. On an average, the country’s population is rising at approximately 3 percent annually. At present, the per capita water supply in Jordan is 200 cubic meter per year. An interesting thing to know here is this the current per capita is one-third of the global average. Not just this, it is also predicted that by the year 2025, the per capita water availability will decrease to 90 cubic meter which would make the entire situation even worse. According to surveys, in the last ten years, the cost of water in Jordan has gone up to 30 percent as a result of the shortage of groundwater. Making the entire scenario even worse are the Syrian refugees in the country.

In order to overcome the water crisis in Jordan, the government is planning to dig seven new wells to reach a deep aquifer containing water from 10,000 to 30,000 years ago.

United Arab Emirates (UAE)

The next country facing water scarcity is the United Arab Emirates. Just to let you know, this gulf country has the world’s highest per capita consumption of water. Currently, the country is facing several water management challenges. This includes, scarcity of groundwater reserves, the high cost of producing drinking water, high salinity levels in existing groundwater, and limited re-use of water. Such is the severity of the water crisis in UAE that it is among the top 10 arid countries in the world. Not just this, the country also consumed world’s 15 per cent desalinated water. Experts have predicted that UAE will completely run out of fresh water in the next 50 years. Since UAE is majorly relying on desalinated water, groundwater and treated wastewater, it is reckoned to be one of the least water secure countries in the world.

To overcome the crisis, the nation has started investing in cloud seeding technology to increase the rainfall. As per a report published by Environmental Agency Abu Dhabi (EAD), if mitigation measures are taken now, both brackish underground water and freshwater in UAE aquifer system will be exhausted within 55 years.

Egypt Water Shortage

In recent years, Egypt has become one of those countries facing water shortage. Inefficient irrigation techniques, misuse of water and uneven water distribution are some major factors behind water crisis in Egypt. The country only has 20 cubic meter per person of internal renewable freshwater resources. As a result of this, the nation heavily relies on the water of the Nile River and 97 per cent of the country’s water comes from the river. Apart from the primary source of drinking water, the river is also the backbone of the country’s agricultural and industrial sectors. However, the excessive use of the river water is making it highly contaminated because of residential waste and untreated agriculture waste. As a result of that, the UN predicted water shortage in the country by 2025. As per the figures of the World Health Organization, Egypt is one of the top lower-middle income countries with high numbers of deaths related to water pollution.

Japan Water Shortage

It’s a surprise that the world’s most high-tech country can also be under the threat of running out of water in the near future. The capital city of Japan, Tokyo, is the largest water-stressed city in the world. Be it melted snow, rivers, lakes or four months of concentrated rainfall, the city relies mainly on above-ground water sources. The 70 per cent of the water supply comes from these sources. But, when there is a dry spell in Tokyo in terms of rainfall, the city faces water shortage in once in every decade since the 1960s. To overcome the situation of the water crisis in Tokyo, the government has invested in pipeline infrastructure to reduce the waste leakage to only 3 per cent.

Mexico Water Crisis

Mexico is one of those countries that is experiencing some serious water crisis in the world. The capital city of Mexico is home to about 21 million people which is about 20 percent of the entire country’s population. Not only this, one in every five citizens in Mexico are lacking access to freshwater. The condition is deteriorating in a way that people only receive water once a week from a truck for which they have to pay. Not just this, the people also have to wait in a queue for hours, sometimes overnight out of fear of the truck will run out of water. Making the entire scenario even worse is the scorching temperature that results in longer and frequent droughts.

The aquifer water level in Mexico is also dropping continuously. Also, flooding is also one of the major concerns that contribute to the water crisis in Mexico. Flooding events cause many problems; out of which overflowing of sewage is a major concern. Also, the city’s water pipes are poorly maintained, and hence are prone to leaks making the city lose 980 liters of its water in a second. Due to the lack of funds, the authorities are helpless.

Iran Water Crisis

Iran is another country which is facing water problem because of its surging population. The country has a population of more than 80 million. Iran is one of the top four countries facing water crisis and the two-thirds of its land is an arid desert. One of the major reasons for the water shortage in Iran is drought that occurs almost every year due to lack of storage dams. Not just this, poor water management is polluting the sparse water resources. One of the largest lakes in Iran – Lake Urmia, has also shrunk to 10 percent of its original size because of increased salinity. Besides, water consumption in the country is more than 3 times the global average. As per NASA’s 2013 report, Iran will experience the worst water crisis by 2030.

England Water Crisis

Well, seeing England on this list might come as a surprise to you. But we cannot ignore the fact that the capital city of London is a major victim of it. A report published by Labor's Leonie Cooper states that the city’s loss of green space, ageing water pipes and growing population are increasing the risk of drought and flooding. From 2015 to February 2019, more than 26,000 pipes have bursted in London. In March 2019, the Environment Agency also warned that the South East of England could also run out of water in the next 25 years because of drastic climate change.

China Water Shortage

A major reason behind the water crisis in the above-listed countries is the rising population. Being the most populated country in the world, China is on the verge of losing its freshwater in near future. It’s capital city, Beijing is the largest water scarce city in China. As per the World Bank, water scarcity is classified as when people in a city/region are not receiving 1,000 cubic meters of fresh water supply per person a year. And in the year 2014, the 20 million residents of Beijing were receiving 145 cubic meters of fresh water per individual a year.

A fact to learn is, despite accommodating 20 percent of the world’s population, China has only 7 per cent of the world’s fresh water. Currently, 70 percent of Beijing’s water supply comes from South-to-North water diversion project. But the project won’t provide enough water for the people of Beijing in the long-term. In addition, the city is also relying heavily on groundwater, which is resulting in depleting aquifers and causing land subsidence. Adding more problems to this entire scenario of the water crisis in China is the water quality report of 2017 which states that 39.9 percent of Beijing’s water is polluted for use.

Although the problem of water shortage was detected decades ago, but the negligence of the authorities and the general public toward this serious issue have brought the world to this brink of losing its most essential element. We don’t know what the future holds for us, and thus, we need to take immediate actions by understanding the consequences of water scarcity. Don’t wait for someone else to solve the problem, do it by taking small steps towards water conservation, so that your country does not become a victim of this life-threatening crisis.

-

4:07

4:07

FeedStarvingChildrenOrg

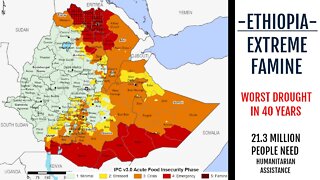

1 year agoEthiopia Starvation Emergency - Worst Drought in 40 years has caused Unimaginable Hunger

139 -

5:45

5:45

FeedStarvingChildrenOrg

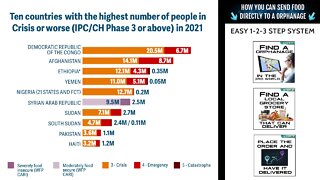

1 year agoTop 10 Countries in EXTREME HUNGER in 2021

80 -

27:01

27:01

The Memory Hole

4 months agoUnseen Horrors: The Forgotten Crisis of Bangladesh (1975)

934 -

3:56

3:56

Just Facts

1 year agoClimate Change is Not Causing Famines

11.6K7 -

6:12

6:12

Last World News Channel

1 year agoCholera pushes health systems around the world to their limits

9 -

4:40

4:40

FeedStarvingChildrenOrg

1 year agoWE CAN END WORLD HUNGER

73 -

24:41

24:41

ADAPT2030

1 year ago $0.50 earned(2/2) The Timeless Hunger Famine Cycle Returns 2024

9443 -

11:22

11:22

FeedStarvingChildrenOrg

9 months agoEND WORLD HUNGER News - Ep.1 - Countless Children are Starving to Death around the planet RIGHT NOW

70 -

6:57

6:57

Creative Society

10 months agoDROUGHT 2023: A Global Crisis Unleashed

1.09K4 -

13:09

13:09

Poplar Preparedness

1 year agoRecord Food Shortages & Famines Due To BAD Harvests (Worldwide)

1901